In early 1933, due to the repercussions of the 1931 September 18th Manchuria Incident and subsequent September 1932 Chinese-rebel attack on the Fushun mine, the family decided to move to Mukden, or Fengtian as the Japanese named it (now Shenyang). These repercussions included visits by the Japanese Police (some sources say he was actually arrested), who suspected father Yamaguchi of 'collusion with the enemy'. After-all, he was teaching 'the enemy's language' and on speaking terms with many of them wasn't he? In her memoir, Yoshiko implies that Fumio had even been trying to be a peace-maker between the two sides; the Police suspected he had some knowledge about the 'bandit attack'.

1919 1932

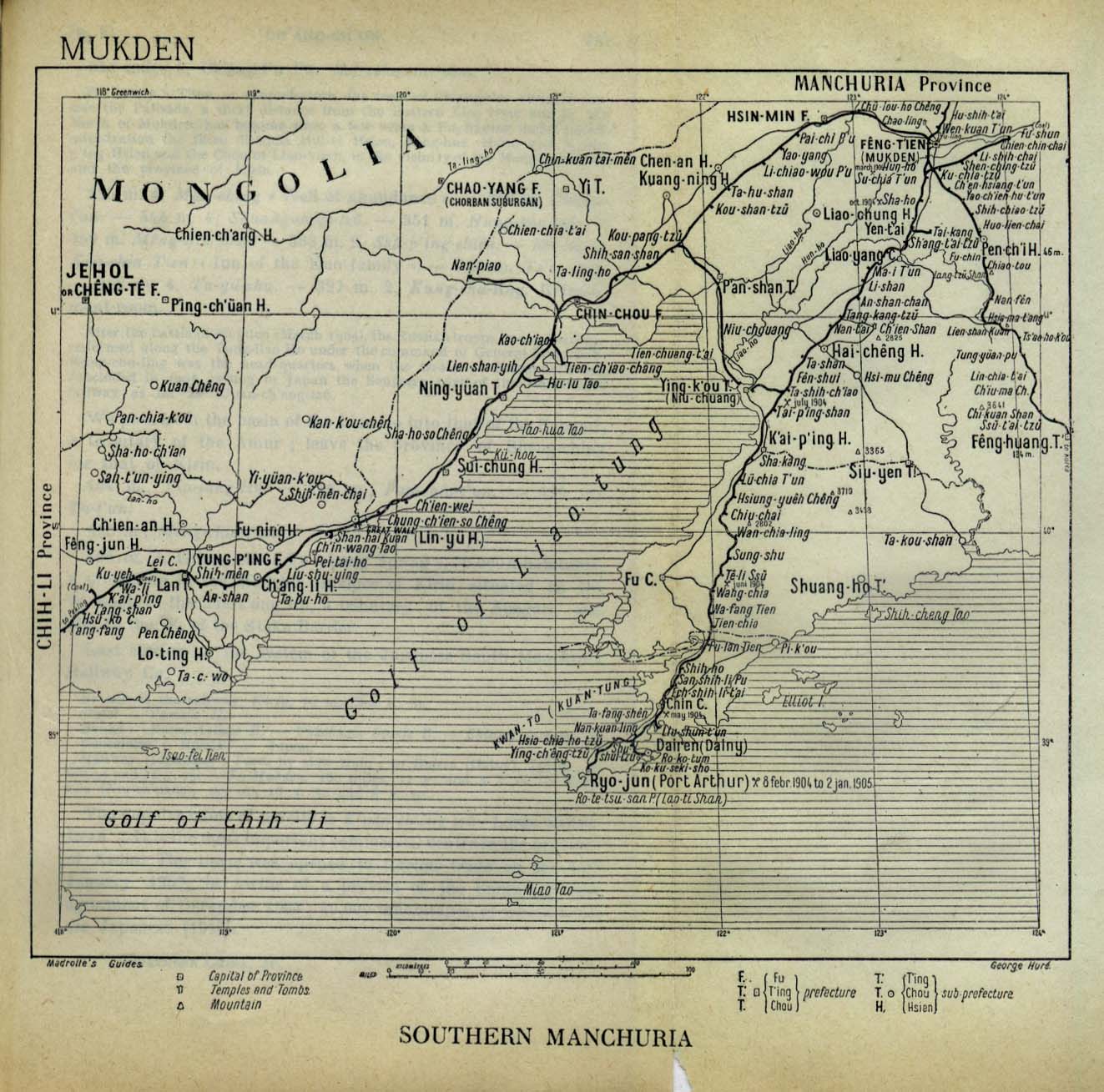

Historically, this city was the location of the great battle of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, when some 275,000 Japanese troops drove back an equal number of Russians. The loss of life was horrendous, approximately 160,000 in total. 1919 1932

Mukden (above maps) was a beautiful and cultured city, cosmopolitan and international; Yoshiko states as a 13yr old "it was my castle of dreams". It was the former capitol city of the Manchu dynasty, filled with 1,000 year old architectural relics. And not only that: it was an integral part of the industrial powerhouse built by the South Manchurian Railway Company and the Japanese government in south Manchuria. You can see the scale of development in the many new roads

The map of Mukden reveals a lot: purple area in center is the ancient walled city, surrounded by a circular wall or ring-road, this comprised the Chinese area. Orange area of map is the railroad station and new area built by the Japanese (in other words, these 'imperialists' did not displace the existing Chinese order, they just added to it). On the right side of 1932 map (blank area) is the Mukden Arsenal, which unfortunately was the source of most of the assault weaponry which Japan used to try and conquer China (many Chinese also worked in the arsenal). Below is a current picture of some arsenal buildings:

Bridges, buildings, and civil engineering works of all kinds shown in the pictures below would be MAJOR construction projects, even by today's standards. That men were able to construct such works without computers and cell-phones is amazing from our modern point of view. below, the Yalu River Bridge (which was later broken by an American bombing campaign during the Korean War):

above: the Showa Steel Complex at Anshan.

from a book on Manchuria, dated 1922:

The crucial battles occurred in and around Mukden and Fushun, the very place that Yoshiko Yamaguchi originated from: she was at the nexus of history and her history is synonymous with the history of Japan's involvement in Manchuria. [Ed. that one of the most well-known books about Manchuria (Louise Young's "Japan's Total Empire") makes no reference to Li Xianglan is a particularly shocking example of academic prejudice.]

As we look at this military map more than 100 years after the battle, it may not occur to the viewer that hundreds of thousands of Russian and Japanese men were fighting to their deaths in these hills while believing they were fighting for "The Glory of Mother Russia" or "The Glory of Yamato Japan". In hindsight, can there be any doubt they were actually dying for life-giving resources and commercial interests? As Yamaguchi says in her memoirs, we have an unflinching duty to look at history with open eyes.

x--x--x--x--x

The Russians built many of the regions landmark buildings, such as this Catholic Cathedral; the Chinese have (surprisingly) preserved it to this day, with many wedding ceremonies being performed there:

above: the Mukden Station, before and after Japanese built the new one. Recently the Chinese built a new railway station in Africa (my, how times have both changed and stayed the same).

- the same station as it still looks today over 100yrs old (many old landmarks were built by Russians, and the Japanese also built very solid structures throughout Manchuria).

here are beautiful color pictures of Mukden in the 1930's, along with some great history.

Yoshiko mentions this street in her memoirs, the famous Naniwa Dori in Mukden:

she also mentions Siping street in the Chinese district:

you may notice the dirt road above, which became a muddy mess during rainy season. The Japanese constructed state-of-the-art roads and structures in their areas.

at the age of 13, she would have taken this electric tram around the city: (Really?? how is it possible that 90 years ago, Mukden had a more sophisticated public transport infrastructure then most US cities (including Los Angeles) have today):

This video has the very best video and still photos of Fengtian as it looked in the 1930s:

here are some stores selling foreign-made goods (is it possible that the Bakery on the left is the shop owned by Lyuba's family?):

the Modern Ladies Tailor:

Father had an old friend in Fengtian, a powerful 'blood brother' named General Li Jichun (picture to right); the Yamaguchi family moves into a large 3-story house inside the Li family compound. In return, the family cares for the second wife of Li (she has bound-feet in accord with the old practice in China). Yoshiko has a great affection for this hobbling lady "whose spoken Mandarin sounded like singing" and she "learns Mandarin from her from morning till night". Yoshiko would also help madame Li to massage her sore feet. The Yamaguchi family lived in the area to the west of the old city walls where all the foreign concessions and consulates were located. She lists her address as #111 Shengxuan-li (streetname), Sanjing-lu (3 classics road), Waishangbudi (Foreign area), Xiaoxibian Menwai (small west gate), Fengtian City. (Thanks to reader Wen Z. for researching this location/information.)

Father had an old friend in Fengtian, a powerful 'blood brother' named General Li Jichun (picture to right); the Yamaguchi family moves into a large 3-story house inside the Li family compound. In return, the family cares for the second wife of Li (she has bound-feet in accord with the old practice in China). Yoshiko has a great affection for this hobbling lady "whose spoken Mandarin sounded like singing" and she "learns Mandarin from her from morning till night". Yoshiko would also help madame Li to massage her sore feet. The Yamaguchi family lived in the area to the west of the old city walls where all the foreign concessions and consulates were located. She lists her address as #111 Shengxuan-li (streetname), Sanjing-lu (3 classics road), Waishangbudi (Foreign area), Xiaoxibian Menwai (small west gate), Fengtian City. (Thanks to reader Wen Z. for researching this location/information.)

Below is a 1920's view of small west gate (Xiaoximen). Yoshiko said "this photo is so familiar, I lived near here and went through this gate when I went to school. The street was lively but then you turn the corner and enter a small Hutong to get to the house we lived in. On the main street are oxcarts used by farmers and many bicycles and rickshaws (yancho)."

Shenyang reader Andrea has contributed the following info regarding the small west gate and da ximen (the big west gate): "The Xiaoyimen in Shenyang has already been demolished. Xiaoyimen, also known as the Outer City Gate, was built from the first year of Tiancong (1627) to the fifth year of Tiancong (1631), and its exact location was at the intersection of Xishuncheng Street and Zhongjie Road today. In July 1951, Xiaoyimen was demolished due to the needs of urban construction. And the Daximen, also known as Huaiyuanmen, was demolished in 1936. However, in 1994, the Shenhe District Government restored it at its original site according to the original regulations. These city gates all had important positions in history. They were not only the entrances and exits of the city, but also important military defense facilities, carrying the history and cultural memories of Shenyang. Now, the restored Huaiyuanmen has become a historical and cultural scenic spot in Shenyang."

below, the view in later years:

below map from Mainichi Special Edition, showing small west gate in center surrounded by various consulates:

below would have been the solid architectural style of the 3 story house the Yamaguchi family lived in, although perhaps not as ornamented (and certainly not a wood house, but one made of solid brick, stone walls, and concrete floors):

This site has photos and info about old historic buildings in Mukden:

the American Consulate in Mukden located in a former Chinese temple:

The old General is enjoying his senior years following a violent past fighting in north-eastern China, and he treats Yoshiko as though she were his own daughter. With her father Fumio's blessing and in an elaborate formal ceremony, the Li family adopts Yoshiko and gives her the Chinese name 李香蘭 (this according to Yamaguchi's memoirs). The picture below is her name: Lǐ Xiāng Lán 李香蘭 the family name of Li and Xiang Lan (meaning fragrant orchid). In spoken Mandarin, it has a particularly nice 'ring' to it and is a beautiful name, pronounced in English as: Lee Shiang Lan (the last syllable in rising tone).

Sidenote: for those wishing to research further, please know you can copy the above Chinese characters into various search engines.

These were not the only families from different cultures coming together, adopting, inter-marrying, and taking steps to try and ensure their future. There seems to have been more of a 'camaraderie' between peoples than you see in today's society; it was normal to 'adopt' and accept other people once the relationship became close enough to formalize. You could say this was a less legalistic arrangement then what we have at present, and it led to many alliances among people who felt the same way.

To continue the thought, many Japanese and Chinese at this time functioned in a cultural mix encompassing business, education, politics, military, etc. Prominent Chinese at the time went to complete their studies in Japan, while many Japanese intellectuals looked to China for ancient wisdom. It's a sad commentary on modernity and all it's technological wonders, that one of it's effects is the insularity and rigidity between nation-states that we observe today.

No one had a crystal ball allowing them to foresee the future, and these 1930's adults clearly hoped for the best and a future of peaceful cooperation between Japan, China, and Russia. Sadly for Yoshiko and many others like her, political and international events (war) overtook all their hopes and dreams. Many did not survive the times, which makes Yoshiko's story all the more remarkable.

As the prospect of war increases (and following her recuperation from tuberculosis), Yoshiko's father and General Li decide that she will move south, to another powerful family friend located in central Beijing (Peking) in order to continue her Chinese education there. Father had always been planning a career for Yoshiko (such as diplomatic translator or perhaps a politician's secretary) which would take advantage of her linguistic skills. He could not have imagined the astounding career which linguistics, music, and the lively personality of Yoshiko was going to attain.

It was at this time that Yoshiko tried to find Lyuba (in order to give her the news about moving to Peking), but the whole family was gone, having fled the police. Their house was ransacked and boarded up. Fully armed Japanese soldiers with sabres at their sides shooed away the crying 14yr old Yoshiko calling for "my Lyubochka".

As mentioned previously, it was Lyuba (a Russian-Jewish girl, above picture) who was responsible for Yoshiko's development as a singer, and in her memoir Yoshiko gives her full credit for it.

By this time, Yoshiko had already had her 1933 'coming out' concert at the Yamato Hotel, been chosen by the Fengtian Radio Station as the only girl capable of singing and communicating in several languages, and was rapidly learning the art of singing while accompanied by live bands on the radio. The name by which she became known all across Manchuria was Li Xianglan [a perfect stage name because if her real name was used (like if it was *Stefani Germanotta] she would not have become known at all [just like *Lady Gaga became known by all].

Yoshiko was indeed a very special person to have accomplished all this by the age of 14.

On the subject of changing one's name when entering 'show business' (or the Showa Business as one wit has called it): is there any need to mention here all the Hollywood actors with names such as Issur Danielovitch, who found the name of Kirk Douglas to be much easier on the ears of his intended audience? I don't see anyone throwing rocks at Mr. Danielovitch (or anyone else who has done the same thing) for the crime of masquerading as someone else. Shall we mention all the famous Hollywood actors of one race (such as Anthony Quinn) who successfully passed as other races (and managed to keep their real race a secret for many years)? And while we are in this territory, what about the propaganda films of Hollywood that have had both overt and covert political and social agendas? Let's not be hypocrites.

x--x--x--x--x

Yoshiko recalls her May 1934 train-trip from Mukden to Beijing; her father bought her a ticket at the Mukden Station and says "You'll be living as a Chinese person from now on, so get used to it." Of course, she thought he would be travelling with her, but due to some business foul-up of some kind, she found herself travelling alone !

She recounts the harrowing night-journey by train from Fengtian to Beijing, a distance of 470 miles: a lone 14yr old girl in the 'hard-seats' (the common-folk section), pretending to be Chinese due to the anti-Japanese sentiment, in the midst of pouring rain, lightning, howling wind, and worries about being robbed or attacked by bandits or guerrillas. This was the type of damage to trains the 'bandits' were causing:

Yoshiko tells about a harrowing slow crossing over a long railroad bridge barely higher than the flooded river below. Oh, and she was hiding a bundle of money in her clothes for her father which she was afraid would be confiscated along the way - she was terrified!

No Japanese would take such a long trip through bandit territory unless they were military men, and here was this little sparrow of a girl, at one point hiding in the train's bathroom from the Conductor. The 'hard seat' section of the train was filled with Chinese farmer people, chickens, other animals, and the stench of garlic and urine was thick in the air. Talk about having to grow up fast and think on your feet !

Here's the old train route from Mukden south to Beijing:

the long railroad bridge over a flooded river below was most likely at Shan-hai-kuan, at the river delta flood-plain:

this was the SMR company brochure map, showing the Great Wall ending in Shan-hai-kuan:

On a sunny blue-sky day the following morning, the train passes through scenes of beautiful flowers growing out of the ancient stone city-walls. She eventually arrives at the Beijing train station, set between two enormous structures, the Guardhouse and the Chien Men Gate:

the Beijing station where Father waited to pick her up, and with a pat on the head complimented her on making the journey by herself:

The second influential 'blood-brother' (who will become her sponsor and guardian in Peking) is named Pan Yugui (this picture evidently taken while he was in prison after the war):

This photo of the Pan family was taken when Yoshiko was perhaps 15yrs old (she is sitting second from right):

The Pan residence is located inside the below shaded area (to the left of the lightly shaded central portion) known as the Inner City - map is from U.S. Department of War circa 1930:

Yoshiko is the only Japanese speaker in the household, and doesn't know any other Japanese people in Beijing either, so at first she leads a lonely life and is forced to totally immerse herself in Mandarin. She is befriended by two of her adoptive sisters, and they all attend school and take various lessons together.

Mr. Pan, born Chinese, is another 'cross-cultural' person, having attended Japan's Waseda University, and he is by no means the only example of such people who due to circumstance, traveled easily between and understood both cultures. In the case of Pan Yugui, he was skillful enough to rise to very powerful positions in Northeastern China while working (some would say collaborating) with the Japanese (and was able to avoid execution after the war because of various 'good-works' he accomplished for Chinese people as well). [Yoshiko's first adoptive father, General Li Jichun on the other hand, was executed sometime after the war ended.]

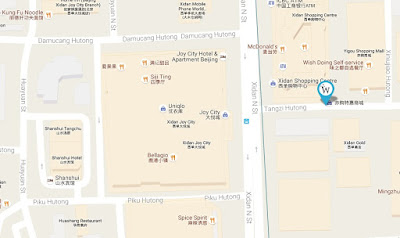

The Pan compound was off Picai Hutong, close by the Forbidden City (see red bubble on left at bottom below):

If you click on the map, you can see the lakes (Seas) and other areas of the Forbidden City which Yoshiko frequently mentions as being among her favorite places to visit after school.

she mentions "The main gate to the Pan household was situated at the center of a large earthen wall on the south side facing the Picai Hutong and continuing for several blocks." and "the neighboring house belonged to the renowned painter Qi Baishi":

She would've seen this type of ancient dynastic architecture:

one of her favorite places for contemplation, the Tai Miao temple:

the famous Chien Men Gate:

She must have fantasized about being a royal Chinese princess during such horse-rides because she seems to know and love each structure of note inside the Forbidden City. She mentions this "eye-catching white pagoda towering over a green island" in Beihai Park:

Beihai Park's "Northern Sea", (see above map also) which Yoshiko rode around on horseback and where she once saw a huge turtle jump out of the water, wondering if the turtle was still alive today:

Below is a 'mystery' photo showing from left to right: father Fumio, a son of Mr. Pan, Yoshiko, mother Ai seated, sister Kyoko, and a priest:

x--x--x--x--x

Modelling for a well-known painter:Yoshiko Yamaguchi at approximate age sixteen:

She recounts her experiences modelling for the well-known painter, Umehara Ryuzaburo, known for having "a sharp eye for beauty", and for painting a series of 'maiden portraits' (some nude), as well as many paintings of the beautiful Imperial palace grounds. Undoubtedly, Umehara also asked Yoshiko to pose in the nude; her answer for all the world to see is shown below in his portrait number 20.

Umehara famously tells her "a cat's face can show two hundred different expressions, and yours has more than a cat's. It's quite an amazing face that changes every time I look at it." He also observed "Your right eye is different from your left: the right one conveys flights of unfettered imagination, and the left one a serenity with a trace of bashfulness". How observant this painter is! This might be a picture-study which he took of her face (since it shows what appears to be an artist's easel.

Number 20 of his 'maiden portraits' was acquired later in life by Yamaguchi and hung in her Tokyo living room (see the year 2014); indeed the right and left eyes have completely different expressions, according to Yoshiko "just like a Picasso portrait". and here is that same portrait, alive again:

I must say that at first, I didn't 'get it' but the more I look at it, the more I appreciate what Umehara accomplished. He captured the seventeen year old Yamaguchi in every separate element, but amazingly, not in a photo-realistic way. Although I say "appreciate", I prefer to see beauty captured (enraptured) in a realist way, ala like the way Gustav Klimpt painted it. If all we had were a couple of photos and the painting #20, I'm sure we all would chose the photos to remember Yoshiko's real beauty.

x--x--x--x--x

While living with the Pan family, Yoshiko recounts some interesting every-day experiences. She frequently awoke to "performances by the pipe ensemble of the pigeons of Picai Hutong." As the sun would rise [no, the phrase she uses is "as the eastern sky began to light up"] in the morning, a large formation of pigeons would soar into the sky; little pipes made of bamboo were tied to the birds feet and would whistle when the birds swooped and soared, providing a natural 'alarm clock' as the day dawned for the Hutong residents. Only the ancient Chinese could've thought of harnessing pigeons in flight to provide a "pipe ensemble" which made such a delightful sound! The bathing situation of the Pan family was less than ideal: although they had modern western fixtures such as bathtubs, there was no running water, so washing had to be done the old-fashioned way, which involved basins of warm-water. For full baths, the whole family would spend a whole pleasurable day at a large public bathhouse, followed by a luxurious meal at a fine restaurant, complete with music provided by an er'hu (Chinese violin) player.

Along with Pan Shuhua's duties as Mr. Pan's helper/secretary, she had other chores to perform, one of which was preparing opium for Mr. Pan and his guests. This involved heating a portion of thick brownish syrup in a small ivory bowl, congealing it on a long needle, and then reheating it to create a nice 'smoke' which was then inhaled from a long opium pipe. When Yoshiko grew older and "looked back on her Beijing years", she was "surprised that such important people like Pan had turned into habitual abusers of opium."

I'm sure she made use of such experiences when it came time to make her famous "Eternity" film whose plotline revolves around the pernicious effects of opium, and indeed, one of her most famous songs is called the "Quitting Opium Song."

While with the Pan family, Yoshiko conveys an interesting exchange with her adoptive mother concerning her 'Japanese habits'.

One day Madame Pan takes her aside and gives her some advice: "First, stop smiling so much when there is nothing to smile about! (the Japanese custom is for a woman to smile constantly in order to be polite and 'charming'). The Chinese call this "selling one's smile" and it is looked upon with contempt. Second, stop bowing so much! "it's all right to nod your head slightly, but stop making such deep bows as the Japanese do. We regard that as servile behavior." Yoshiko takes this advice to heart, and says that her later experiences in Europe and the United States confirmed people's mannerisms were similar to those of China.

The interesting thing about the above is that it shows how Madame Pan takes genuine care of her adopted daughter, and it gives us an insight into a very human situation.

This is yet another example of how Yoshiko came to prefer Chinese over Japanese social mores; the Japanese were constricting, filled with various duties which had to be honored, whereas the Chinese were more free and easy. Take the example of simply laughing at something one finds funny: the Japanese girl will 'politely' cover her mouth, whereas the Chinese will more often laugh out loud as western people do.

However, this did cause some problems when Yoshiko would return home to visit her parents and her natural mother Aiko would bemoan how "the big city life had corrupted" her Japanese etiquette. It's here we get some insight into how difficult a task it was for Yoshiko to actually 'become Chinese', because it meant 'losing her Japanese character', and of course the reverse was true also. This would not have been any great problem if both her "parents" (ie, Japan and China) had not been at war with one another.

High School

She attends the Beijing Yijiao Girls School 北京 一角 中学 (a Chinese mission school mainly attended by rich 'pillars of society' girls - caption on picture below). The Wikipedia link says that Yoshiko graduated in 1937, but this is not documented. This school must have been located inside the Inner City (see above map) where there are several locations of Catholic Mission Schools. The following internet site places the Yi school in Tangzi alley:

Here is a photo of the Beijing Yijiao Highschool graduating class of 1935:

walking home from school:

While in this school, Yoshiko's Mandarin is so perfect that her classmates have no idea about her Japanese up-bringing and assume she is 'a Peking home girl'. And Yoshiko does not reveal anything to them either because "well, in that era, there was a vigorous anti-Japanese movement and so I tried to avoid being identified as Japanese completely". Actually, this is such an understatement of Peking social conditions at this time! It would've been absolutely dangerous to be revealed as Japanese, to the extent of being stoned or beaten to death since the prevailing anti-Japanese feelings were running so high!

x--x--x--x--x

At this time in Yoshiko's life, it's important to understand some specifics of the Japanese Army's assault on China. The following is based on the work of historian Rana Mitter (he has spearheaded the effort to cast light on this period of history which many in the west frankly do not even know about). His book Forgotten Ally - China's World War II 1937 - 1945 is an excellent summary of the WW2 period from the point of view of China, and more specifically the three main Chinese protagonists: Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Zedong, and Wang Jingwei (ie, the Nationalist, the Communist, and the Collaborationist). Mitter makes a strong case that China (the forgotten Allied power as he terms it) needs to be restored to it's rightful place alongside the U.S., Russia, and Britain, in WW2 history.

Significant Events:

Following the 'Manchurian Incident' in Sep 1931, fighting broke out in Shanghai between Chinese and Japanese forces in Feb 1932; although it was a short conflict lasting three weeks, some 14,000 Chinese troops were killed, over 3,000 Japanese, and 10,000 civilians.

In 1933, the Japanese invaded and occupied the province of Rehe (Jehol).

In mid-1934 the Communist "Long March" began in Jiangxi, ending in late 1935 in Shaanxi province, led by Mao. Only one in ten of the 80,000 participants survived this march.

Also in Nov 1935, the 'hated collaborator' Wang Jingwei

barely survived an attempted assassination. Wang is someone who as one of the original Chinese nationalists is now called a traitor; he accurately foresaw (1) that Japan's forces were superior to Chinese forces, (2) that tremendous suffering would hence be caused to China by Japan, and (3) he calculated that China would be better off by cooperating with Japan at the time instead of throwing everything into the resistance. A more nuanced approach that would allow China to muster her strength in the western areas while ceding the coastal areas to the Japanese. At one time, Wang was the better known and stronger political force than Chiang.

Japan had it's own political upheavals: in Feb 1936, some army officers attempted to overthrow the civilian led government and murdered several senior government officials. The plotters were executed, but their actions (like the Manchurian Incident itself) had the effect of driving the country further in the direction of militarism and "showing a stronger hand in China".

Japan was also casting a wary eye towards it's Manchukuo northern border and Russia, where clashes were occurring since 1935. The Japanese Army believed they would have to go to war against the Soviet Union in future, and this affected their attitude towards China.

By the spring of 1936, violent incidents against Japanese interests were happening in various parts of China, further increasing the pressure on Tokyo to beef up the military in China.

In Dec 1936, Chiang Kai-shek was kidnapped by the 'Young Marshall' Zhang Xueliang and another war-lord. Zhang was the son of the "Old Marshall" Zhang Zuolin, the war-lord of Manchuria, who had been murdered by the Japanese in June 1928 (once again by means of an explosive charge on the South Manchuria railway, which completely destroyed a railroad bridge and his personal train on it). Pictures of 918 Incident and Zhang explosion.

The kidnappers demanded that Chiang cease attacking the Communists and instead lead a United Front against the Japanese; Chiang was only released after agreeing to this demand. All of China rejoiced on Christmas Day 1936 when Chiang was released (Yoshiko was probably in her junior year at this time, which is why she recounts the many student-led protests and flag-waving processions happening regularly in Beijing).

x--x--x--x--x

During these school years, it was a common practice for all the students to attend rallies and shout political slogans of one kind or another. Some supported the unification of Nationalist and Communist forces in order to fight the common enemy, Japan. Here's one such large rally:

Usually Yoshiko tried to avoid attending these volatile student demonstration rallies, because it caused her so much internal conflict (that the side she loved was criticizing and calling for death to the side she had been born into). The inflamed passions of the Chinese students could easily have become dangerous for anyone found out to be Japanese.

At one such student rally at the Forbidden City which she could not avoid, when it came time for Yoshiko's declaration, she stood and said "I will stand on the rampart wall of Peking" [meaning, to get shot by a bullet from either the attacking side or the defending side].Of course, given the situation of danger present, it would've been completely understandable to say anything including 'I will stand on the city wall in order to defend the city'.

A movie about her life depicted the city wall with Yoshiko standing on it thusly:

We can only imagine Yamaguchi's state of mind in these trying circumstances she found herself in. We know that she studied Chinese since kindergarten (virtually the same as a native-born Chinese). We know she has unusually beautiful features and "a good ear" for music. She's been studying western music forms for years. But what was she thinking about her identity or her nationalism: was it Japanese or Chinese? At this point she had not even been to Japan; her home-ground, ie, the place where she grew up running through the fields was Manchuria! Her memoirs say she was absolutely torn between both sides.

She was living with the Pan family in Beijing as a Chinese girl and attending what we would now call 'high school' (but in terms of rigorous study probably our college level) in Beijing. She was "eating, sleeping, and dreaming in Chinese" according to her memoir, and she specifically says "she was in the process of transforming herself into a person of indeterminate ethnic background" as a matter of choice and also survival.

x--x--x--x--x

Both of her adoptive families were very substantial, anti-communist, pro KMT, and sympathetic towards the Japanese governing Manchuria. It was a complex time in Chinese history, with the Nationalists battling against various warlords and the communists while trying to unify the country under their rule, and everyone worried about the coming conflict with the Japanese.

Some critics imply Yamaguchi took Chinese names in order to conceal her real identity as a Japanese girl - this is erroneous - she felt genuinely attached to Chinese culture which she had studied since kindergarten, and the names came first, prior to all the subsequent intrigue.

She was formally adopted by these families in accordance with Chinese customs of the time; adoption was certainly not unusual in the upheavals which engulfed China. It was only natural to continue using her Li Xianglan name when her music and subsequent film career began. In addition, there was no big 'conspiracy' to hide her Japanese name; it was used as such in some films and newspaper articles at the time also. Many people (including her fellow actors and actresses) suspected she was a 'half' (or happa in Hawaiian) of both Japanese and Chinese parentage.

Most of her photos show her in a high-collared Chinese ‘qipao’ dress, even in Japan. Yoshiko herself said ‘I was a Chinese made by Japanese hands’. More about this statement later. She also told interviewers that as a young woman she considered China her “home country” and Japan her “ancestral country.” She had always loved them both (somewhat like parents), she told The Globe in 1991, and never fully recovered emotionally from the war between them.

x--x--x--x--x

Yoshiko at age 14 with her father, Fumio Yamaguchi:

The parents should receive the highest accolades for their idealism and work ethic, characteristics which Yoshiko demonstrated throughout her life. What more could we have expected (or can we expect) parents to do for their children, other than what Fumio and Ai did for their child Yoshiko?

another rare family picture; Mother is seated, with the 17yr old Yoshiko on the right (note there are again seven children present - perhaps one was visiting, a helper or a neighbor, or even adopted into the family):

Yoshiko was singing "New Melodies from Manchuria" on the radio at this time; you can hear what these sounded like by clicking the next link and scrolling down to the three videos which yanagi470 has posted here:

http://blog.livedoor.jp/yanagi470/archives/4789091.html

One of the videos - it's the sitting girl with her head turned toward the camera -

"Song of the Fishermen" (sung by Wang Renmei in her hit film of the same name) is mentioned by Yoshiko as being "my very favorite" of these ancient Chinese songs which became popular 'people's songs'. She writes that this song condemned social corruption while voicing resentment over the wretched life of poverty of fishermen:

"Hurry, cast your nets and pull them in with all your might,

Our days are bitter waiting for our catch in the morning mist,

With no fish harvest and heavy taxes,

The ageless sufferings of fishermen!"

this is Yoshiko's version of Song of the Fishermen:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8gVMjV7N5Xw

here is a quite beautiful modern version sung by Shu-Cheen Yu in Australia:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A7dxfS4G0aM

In 1937, Yoshiko sang "Manchurian Girl" (Manchu Musume) on the radio, backed by a live orchestra:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LwMf-TSnVqY

x--x--x--x--x

the famous picture of Yoshiko, perhaps taken at age 16:

at the Temple of Heaven (right): this image of Yoshiko is one of the very few we have of her as a teenager:

Umehara's Temple of Heaven painting:

another look at the alabaster-like beauty of the young Yoshiko:

1937

In the summer of this year, all-out war began. Shanghai would be the first battle, followed by others; Qingdao, Tianjin, Beijing, Taiyuan, Datong, Ji'nan, and then Nanjing.

Up until 1937, Japan had bullied it's way around north China with impunity, but after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident Chiang Kai-shek had marshalled his forces and decided to commence a 'war of resistance'. The Japanese were insulted by the new Chinese 'backbone' and resolved 'to teach China a lesson'. The fighting was vicious, usually involving the bombing of civilians and street-to-street combat. Unbelievable numbers of combatants were killed and wounded (in the tens of thousands). In the first three months of the war, Chiang had more than half a million troops on the ground and some 187,000 of them were killed or wounded. The Japanese had thought an early "shock and awe' campaign would collapse the Chinese resistance as it had often done in past years, but Chiang showed them that China had the will to make a stand and fight and die bravely.

the Japanese army enters Beijing, a fearsome sight for the Chinese populace:

Gen. Matsui Iwane leads his infamous troops into Nanjing, eventual site of horrendous savagery which will never be forgotten:

Summary thoughts on the 1933 - 1937 phase of Yamaguchi's life, by John M.

Yoshiko's idyllic childhood in Fushun ended after the Chinese resistance mounted an attack on the Fushun mine; the family was forced to move to the nearby city of Mukden in early 1933. Yoshiko describes the family's circumstances in Fushun as "difficult", and we can surmise they were ostracized either before or after father had ceased to work at the railroad company.

Most important in understanding Yoshiko's life, is that in this phase of her life, powerful Japanese government people and forces had taken note of her in all respects. When the military police took her father in for questioning, they undoubtedly noted the Chinese language ability of the family, especially Yoshiko. When she sang at the Yamato Hotel in front of the aristocracy of Mukden, it was not only the Fengtian radio people who took notice of her. This very hotel was where the Manchurian Incident had been planned and where the top people all stayed, so it's certain that Yoshiko came to the notice of both government and military types who were actively promoting Japan's interests.

Yoshiko is very specific about the intrigues of one Yamaga Toru (more about him later), and to what extent he was involved at the very center of various "pacification" schemes involved with appealing to the hearts and minds of Chinese people through entertainment, so there is little doubt he influenced her development strongly.

Yoshiko herself writes about her "chance meeting" in 1933 with the well-known singer Awaya Noriko, and recounts taking singing lessons from her: another example of how her talent was noted early on by major personalities and found to be very good.

It may have been an internal family decision to send Yoshiko away to Beijing in 1934, but I'm certain this decision was approved by top people who all had interests in her development. As the eldest child, she was her mother's 'right-hand man' in helping with all the chores connected with five or six other young children, and Aiko must have keenly felt her loss. Given the family's financial position (having to trade the care and keeping of General Lee's wife for the monthly rent) it's questionable they had the resources to send Yoshiko off to Peking to a private high-school and a higher life style. It's more likely that it was a mutually beneficial arrangement supported (and funded) by 'upper management', and it was understood that Yoshiko would eventually become part of Japan's efforts in Manchuria and China.

The family must have had some kind of impulse to give up their beloved Yoshiko to a greater cause: it may have been her personal advancement (moving into a high-society life and attending an exclusive school in Peking) or as Ai (her mom) said "it would be good for our nation". Or perhaps someone (or more likely a committee) made the decision that 100% immersion in Chinese society would be the best way to develop a native-sounding Mandarin ability (which could then be 'utilized' by the State).

Either way: the effect of having to leave her family at the age of early fourteen had profound psychological consequences for her. Her most revealing statements concerning this include "I was a Chinese entity made by Japanese hands" and "I was a spiritual mixed-race child between Japan and China".

As you might expect, one of the consequences was her eventual estrangement from her father (she shed many tears of loneliness in Peking while acclimating and "becoming Chinese" and it was only natural that she developed some resentment toward the people who put her through all this). A secondary consequence was perhaps the internal strain within the Yamaguchi family which her absence and eventual stardom caused (more on this aspect at a later date).

What her family and patrons in Mukden did not foresee was that Yoshiko actually became enthralled by the whole Chinese culture and not just the Mandarin language. They probably figured "we'll send her off to learn Chinese and she'll return as our Japanese Yoshiko".

Wrong! what actually happened is that Yoshiko ended up loving the many cultural aspects of the Chinese she had grown up with in Fushun, even more than her 'Japanese heritage' which she only encountered during her first visit to Japan in 1938. Her adoptive Chinese mothers and fathers also treated her with a kindness that she responded to and makes specific note of in her memoir.

Yoshiko's memoir is very candid about the fact that she felt 'out of place' in Japan and considered China her 'home'. It is filled with direct statements which confirm (1) she enjoyed interacting with the Chinese, (2) that her public and private persona was perceived to be Chinese, and (3) that she did not 'masquerade' as Chinese. Her best friends during the 'China phase' of her life are Chinese people.

Even the name by which she is most recognized in Japan today, "Ri Koran" is indicative of how she is/was accepted in Japan as basically Chinese: Ri Koran is how the Japanese pronounce the Chinese words Li Xianglan.

[Note - the above was written prior to the page titled The Mystery of Yoshiko Yamaguchi.]

::to be continued:

I am not familiar with the practice of adopting the blood brother's children. However it seems to me that Yoshiko's two adaptions by prominent Chinese men served to benefit the Yamaguchi family. General Li hired Fumio to be a caretaker of his second wife and provided housing after he lost his career with the Manchurian Railroad and Mr. Pan supported Yoshiko's high school education. I am surprised that the Yamaguchi family let Yoshiko live with the Pan family at the tender age of 14. She must have been a very brave person to leave her family and live in Beijing as a teenager. -Eddie

ReplyDeleteYou are not the only one who is "surprised" that the Yamaguchi family would subject Yoshiko to danger: the train-ride itself and living with a strange family far from home. Which is why I wrote "The Mystery of Yoshiko Yamaguchi" . Please access this page for a surprising assessment of Yoshiko's biological origin:

Deletehttps://yoshikoyamaguchi.blogspot.com/p/the-mystery-of.html