July 1937: above, Shanghai under assault by Japanese troops. Japanese and Chinese armies clash in the suburbs of Beijing (the Marco Polo Bridge Incident), marking the beginning of full-scale war between China and Japan. However, the pot had been boiling since 1931 and even before, with many an 'incident' occurring; this was the fate of ordinary foot-soldiers trying to conquer (or defend) China:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marco_Polo_Bridge_Incident

a famous spy named Miyagi (a member of the Sorge network) describes the incident: Miyagi returned to Tokyo in mid-1937 and analyzed the reasons for a flare-up between Chinese and Japanese forces in China - the epochal, so-called Marco Polo Bridge Incident which began an eight year war. Below, a depiction of the Incident in a film (The Soong Sisters) and as it might really have looked:

a famous spy named Miyagi (a member of the Sorge network) describes the incident: Miyagi returned to Tokyo in mid-1937 and analyzed the reasons for a flare-up between Chinese and Japanese forces in China - the epochal, so-called Marco Polo Bridge Incident which began an eight year war. Below, a depiction of the Incident in a film (The Soong Sisters) and as it might really have looked:

Miyagi’s ultimate advice to Sorge was that the confrontation (which came about after a Japanese soldier went missing during night-time maneuvers) was largely engineered by the Imperial Japanese Army to direct attention away from domestic problems in Japan, and also to provide an excuse for further expansion of Japanese territory beyond that already grabbed in the northern region of Manchuria. Sorge duly relayed the information to the Soviet Union by clandestine radio.

1937: Fierce anti-Japanese demonstrations are taking place throughout the city (Beijing). Yoshiko has been living in the Pan household since May 1934, but by 1937 life outside the compound is becoming more dangerous.

The head of the household, Pan Yugui has been appointed Mayor of Tianjin and had already left Beijing. Yoshiko's father Fumio is getting worried about the safety of his 17yr old daughter, so he sends two 'close acquaintances' (actually, Japanese intelligence-agent operatives) to visit her and convey certain thoughts concerning her living situation.

Intelligence Agent Aizawa

The first agent, named Aizawa, is a young agent who "used to visit Father in Fengtian." The essence of his meeting with Yoshiko is to convey to her that it is time to return to a Japanese household and a Japanese school, since it is getting too dangerous to remain in the Pan residence as a Chinese girl. In addition, Aizawa is also trying to collect some general intelligence regarding Yoshiko herself, the Pan household, the situation at school, etc.

The first agent, named Aizawa, is a young agent who "used to visit Father in Fengtian." The essence of his meeting with Yoshiko is to convey to her that it is time to return to a Japanese household and a Japanese school, since it is getting too dangerous to remain in the Pan residence as a Chinese girl. In addition, Aizawa is also trying to collect some general intelligence regarding Yoshiko herself, the Pan household, the situation at school, etc.

Pan Shuhua answers him in Mandarin (which at this time came easier to her than Japanese): "my sister and I are still going to school and if I quit now, all my hard work will be for nothing. And if Father and the rest of the family is going to move to Beijing eventually, it makes all the more sense that I remain in Beijing and stay with the Pan family. Now I am Pan Shuhua and a Chinese girl!"

A "Japanese military type" like him (her words) "could hardly have appreciated what hardship she was going through while trying so hard to turn herself into a Chinese girl". In her 17yr old "rebelliousness", she has obvious disdain for "Japanese intelligence agents who had always been acting like bullies to the Chinese."

Wow! in this short candid recollection, Yoshiko reveals a lot to us. First, that it is not only her parents who have an 'interest' in her progress and safety; second, that she prefers being a Chinese girl and has quite succeeded; third, she is quite feisty when defending herself; fourth, she has developed a strong dislike of the 'militarist' mindset and clearly sympathizes with the Chinese point of view towards the Japanese.

Agent Aizawa visits again in a few weeks. And this time he cranks up the pressure on Yoshiko, telling her that 'terrorists' (meaning anti-Japanese partisans) are afoot, targeting Pan Yugui and that it would be best for her to take refuge in the Japanese Embassy grounds. But Pan Shuhua is ready for him this time and even stronger in her reply: "I have no desire after all the efforts I've made, to go back to a Japanese lifestyle. I am well-disposed toward living like the Chinese. Take school as an example, you have no idea how much more free and enjoyable it is here compared to a Japanese girls' school!" [Ed. I can well believe that "I like being Chinese" was watered down to "I am well-disposed toward . . ". in her memoirs.]

Present-day academics who are writing jargon-filled Phd thesis based on "the masquerade of Yoshiko Yamaguchi as a Chinese" have not fully absorbed what Yoshiko herself wrote on paper and put her name to. They continue to mistakenly write "she was really a Japanese in disguise" when the actual reality at this time of her life is that she herself "preferred being Chinese". She was "thinking, speaking, writing, and dreaming in Chinese". And it might be added, also dressing in Chinese clothes.

And it is here, dear reader, that Yamaguchi's story gets even more intriguing.

Intelligence Agent Toru Yamaga

Another 'friend' of her father named Toru Yamaga (sometimes translated as Toru Yanbe) now visits Pan Shuhua, and his participation is fundamental to understanding why Yoshiko eventually felt "used like a puppet" by the Japanese national policy propagandists. He had been visiting the Yamaguchi household often since their arrival in Mukden in 1933.

I paraphrase Yoshiko when she writes in her 1987 memoir: Yamaga Toru was a close acquaintance of Father's in Fengtian, and the title on his card read Army Major for Area Pacification, China Section, Press Division of the Northern China Army Command. He was always working at pacification initiatives, and headed the Yamaga machine, an agency responsible for information dissemination and propaganda in the culture, art, and publicity arenas. He had many acquaintances (especially Chinese women) among those involved in film, theater, and the popular arts. He spoke Mandarin very well, wore finely made Chinese clothes, and had a Chinese persona named Wang Er'ye which he used to promote Japan's 'national policy'.

I paraphrase Yoshiko when she writes in her 1987 memoir: Yamaga Toru was a close acquaintance of Father's in Fengtian, and the title on his card read Army Major for Area Pacification, China Section, Press Division of the Northern China Army Command. He was always working at pacification initiatives, and headed the Yamaga machine, an agency responsible for information dissemination and propaganda in the culture, art, and publicity arenas. He had many acquaintances (especially Chinese women) among those involved in film, theater, and the popular arts. He spoke Mandarin very well, wore finely made Chinese clothes, and had a Chinese persona named Wang Er'ye which he used to promote Japan's 'national policy'.

His style and demeanor made him a charming man; the smile on his face displayed a sense of unperturbed composure, and brought to mind the dignified manners of a Chinese gentleman. Leading a flamboyant lifestyle, he always had a beautiful Chinese actress on his arm. Once, he told Yoshiko "Japanese women have no appeal for me, they are always fidgeting about this and that and I'm totally at a loss as to what they may be thinking."

photo to left: Yamaga and the actress Li Ming.

Like so many other characters that Yoshiko describes in her memoirs, an entertaining movie could be made about Yamaga's life alone. He was born in 1897, making him 23 years older than Yoshiko, but that did not stop him from developing a long-term friendship with her. In the beginning he was her 'knight in shining armor' and confidant, but as time went by, the roles were somewhat reversed in that she became his confidant, and as she became aware of more adult matters, he became less of a 'knight' and more of a 'knave'.

She would later learn that Yamaga was involved in the founding of Fengtian Broadcasting Station and was well-aware of how Yoshiko had been singing "New Melodies from Manchuria" under the name Li Xianglan for several years now. He was also instrumental in the 1937 establishment of the Manchurian Film Association (the same company which will feature Li Xianglan in several controversial 'propaganda' films in the future - but we're jumping a bit ahead of ourselves). So Toru Yamaga is constantly 'scouting for talent', and in the case of Li Xianglan may actually have been in the process of 'molding talent'.

Yamaga Toru is one of the most colorful characters involved in Japan's attempt at 'nation-building' in Manchuria, and the recruitment of talent for that cause. And he is quite skillful in dealing with the rebellious Li Xianglan, as shown by this masterful line: "Now that you've become accustomed to the Chinese way of life as Mr. Pan's adoptive daughter, it would be best to continue with your existing lifestyle as long as the situation allows. It is true that your father Pan Yugui has become a terrorist target, but my own investigation shows that his house is not marked for firebomb attacks. On the other hand, why don't you reconsider your thoughts about becoming a politician's secretary? I myself have no intention of dragging you into my business, [ but that's exactly what I'm going to do! - Ed ] and since you already have a good reputation with the Fengtian Broadcasting Station, why not think about a career as a professional singer with the Beijing Broadcasting Station?"

I don't think we can fault Li Xianglan for her decisions at the young age of 17. She's feeling her power as an individual start to grow and making her own way in the big city of Beijing (which was full of hostile sentiments) and in a time of impending war. She responds to Yamaga that to sing 'pop' songs requires special training which she hasn't had.

She accepts him as "a knight in shining armor" because he befriends her with small loans and buys her things she needs for her social life at the prestigious Yijiao Girls School. She is oblivious to the well-hidden machinations of propaganda boss Yamaga, and not aware of all the intrigues he is involved in; and as a teenager, understandably so.

x--x--x--x--x

Given the care with which Yamaguchi chooses her words in her memoirs, the insights and implications contained in the above paragraphs are obvious. She says later in life, "like Manchukuo, I was a Chinese entity concocted at the hands of the Japanese. It pains me whenever I think about it." hopefully, we can better understand now why she said this.

Given the care with which Yamaguchi chooses her words in her memoirs, the insights and implications contained in the above paragraphs are obvious. She says later in life, "like Manchukuo, I was a Chinese entity concocted at the hands of the Japanese. It pains me whenever I think about it." hopefully, we can better understand now why she said this.

x--x--x--x--x

In July 1937, the 'Marco Polo Bridge' incident occurred, marking the outbreak of war between Japan and China, a full four years and then some before the U.S. itself is attacked at Pearl Harbor in Dec 1941.

As Rana Mitter details in his book "Forgotten Ally - China's WWII 1937-1945", the western world is not fully aware of how valiantly the Chinese fought and died in their millions against the onslaught of more powerful Japanese forces during the 1937 - 1941 period.

At this point in time in Yoshiko's life, it was the summer vacation of 1937 and Pan Shuhua goes to Tianjin (where Mr. Pan has been appointed mayor - see above residence). Her father Fumio also just 'happens' to be in Tianjin (a city about 80 miles south of Peking) while on business:

In what must be one of the worst cases of 'parent inadvertently (or advertently) leads child into danger', Father takes her to an elegant party at an establishment called The House of the Rising East Restaurant. This next episode in Yoshiko's life is stranger than any fiction a Hollywood writer could ever have dreamed up, so I quote her extensively.

The Other Yoshiko (Kawashima)

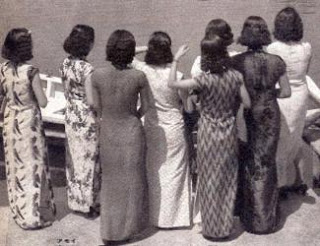

"When we arrived, the restaurant's spacious interior was ablaze in gorgeous colors. In the middle courtyard, a circle of young, high-society Chinese women adorned in an array of colorful dresses were having a good time chatting and laughing among themselves.

"When we arrived, the restaurant's spacious interior was ablaze in gorgeous colors. In the middle courtyard, a circle of young, high-society Chinese women adorned in an array of colorful dresses were having a good time chatting and laughing among themselves.Particularly eye-catching in the midst of this crowd was a white, slender face with a smile exuding flowing elegance.

The person was not particularly tall, but the long, black Chinese qipao, designed for men, concealed a well-proportioned form and produced a sensual beauty evocative of an oyama [a male actor who plays female roles in Kabuki plays]. The soft, short hair, parted more generously on one side, was just slightly slicked. Her full lips combined with the expression in the eyes, changing in sync with the line of vision, together gave off a mischievous charm."

The person was not particularly tall, but the long, black Chinese qipao, designed for men, concealed a well-proportioned form and produced a sensual beauty evocative of an oyama [a male actor who plays female roles in Kabuki plays]. The soft, short hair, parted more generously on one side, was just slightly slicked. Her full lips combined with the expression in the eyes, changing in sync with the line of vision, together gave off a mischievous charm."

"That's Kawashima Yoshiko!" "Commander Jin Bihui!" "Madame Dongzhen!" "Princess Xianyu!" -- I could hear whispers of this sort from the crowd. And so indeed this was Aisin Gioro Xianyu, alias Dongzhen, the fourteenth daughter of Shanqi, the tenth-generation Prince Su from the Qing Imperial family; she was also Commander of the Rehe Pacification Army, and came with the Japanese name Yoshiko Kawashima.

"While I didn't quite understand the implications of a woman dressing in a man's clothes, I did appreciate the extraordinary charm surrounding her alluring beauty. I looked at her as if I were observing a live doll. Kawashima appeared to be a young boy, while in fact at the time she was already over thirty years of age.

"After introducing himself, Father introduced me to her, and with a slight frown playing around her eyebrows, she surveyed me in my Chinese dress from head to toe and then murmured in Chinese, "Ah, so you are Japanese!" Responding in Chinese, I told her that I was a student at Beijing's Yijiao School where only Chinese girls attended, that I had never been to Japan even though I was Japanese, and for that reason I was not familiar with the conditions in Japan.

"Kawashima then surprised me by replying in Japanese, this time assuming a male role: Yoshiko? What a coincidence! I've got the same name. Glad to make your acquaintance. People called me 'Yoko-chan' when I was small, and that's what I'll call you. You, on the other hand, will call me 'Onii-chan' (dear brother).

"As a result of this close bond that developed between "Yoko-chan" and "Onii-chan" at that party, I was often called upon to be Kawashima's guest at various gatherings. She would ask her aide, Ms. Liu, to telephone me, making up all kinds of excuses for an outing. And Pan Shuhua did become a frequent visitor to Kawashima's establishment, The House of the Rising East.

"Kawashima always surrounded herself with what could well be called her own palace guard of fifteen or sixteen young girls. Among these guards, the apparent leader was one Ms. Liu, who was a woman of absolutely unparalleled beauty. Sometimes, Kawashima would appear with a little monkey sitting quietly on her shoulder. Due to pain from previous injuries suffered in military operations, she was in the habit of injecting herself with a syringe filled with drugs. At one time she had assembled and led a military force of thousands of fighters, but now that was all in the past.

"Now her life had descended to one of empty lies, debauchery, and exhibitionism. Kawashima led a life in which the order of day and night was turned completely upside down. She would arise like an apparition at around two in the afternoon and have a light breakfast at around three or four. From then on, friends in two's and three's would gather at her place, or Ms. Liu would summon them by phone. Mealtime for everyone was after ten at night, after which came party time. By then, more of her hangers-on would show up, along with actors and musicians from the Beijing opera. People drank, sang, danced, acted, performed acrobatics and magic, played mahjong, and gambled at cards. The scene became increasingly rambunctious with every passing hour. Just when you thought you'd seen it all, there'd be an exodus of revelers to nightclubs, dance halls, billiard parlors, and cabarets . . . and when fatigue finally took over as night turned into first light of day, it was time for a night snack. It wasn't until around seven in the morning that the revelers would disperse like apparitions.

Yamaguchi continues:

"I went a number of times to Kawashima's wild parties during those summer nights, but once I had satisfied my curiosity, I began to feel disgusted by them. Most of the time, I would leave the party-goers before they called it a 'day', but other girls would stay on for as long as a week. Perhaps one could describe their behavior as a way of living for the moment, of turning their backs on reality when times were getting rough. I came to realize later that Kawashima's lifestyle involved nothing more than abandoning herself to debauchery at a time when she could no longer enjoy the prestige of being a 'Commander', or a 'Mata Hari', or a 'Joan of Arc' as she once had been called.

"For me, this was a time when I was transforming from a young girl into a young woman, a time when I was beginning to develop an interest in the world of grown-ups. I was also getting bored with having nothing else to do but study and with wearing nothing more elegant than the same blue cotton school uniform.

and those alluring summer days, when I could dance away in beautiful Chinese dresses, allowed me a breath of freedom from my prosaic life in Beijing. Kawashima gave me the opportunity to feel emancipated from the regimented routines at home and school (although what really surrounded her was an air of perverse degradation and self-abandoning decadence).

x--x--x--x--x

Once her adoptive father Pan Yugui learned about her association with Kawashima, he gave Pan Shuhua 'a piece of his mind' and demanded she return to Beijing (it was the end of summer anyway). She also received a scolding from Yamaga, the Japanese military-man.

And if the above story is not fantastic enough, it turns out that Yamaga Toru was Kawashima's first love interest! It is here that one has to believe that he had something to do with Yoshiko's introduction to Kawashima, for what specific purposes we may never know. Perhaps Yamaga hoped that Kawashima would seduce the young Yamaguchi and 'turn' her from the ambivalent position she held while going to school in Beijing into giving more support to the Japanese side.

x--x--x--x--x

The story of Yoshiko Kawashima's tragic fate: 'Eastern Jewel' was born a Chinese Imperial Princess, adopted into a Japanese family at age seven, brought up in Japan, abused by her adoptive father, and had great charisma and leadership qualities. She fell in love and out of love with the young cadet Yamaga Toru, tried to commit suicide, joined the Japanese military cause in Manchukuo and China, and leads thousands of troops against Chinese resistance fighters. At one point she was even married to a Prince of Mongolia. She has both male and female characteristics, is wounded in battle, falls out of favor, and was eventually executed by the KMT in 1948 for the crime of treason against China, and that isn't even the half of it! her story reads like a screen-play from beginning to end.

x--x--x--x--x

It is obvious from the candid way that Yamaguchi describes Kawashima, that there was some mutual fascination between the two of them, at least in the summer of 1937. Based on Yamaguchi's memoirs, she did try to avoid contact with Kawashima in succeeding years. Kawashima had a house in Beijing at #34 Dongsi Jiutiao: from a Chinese website:

This rather nondescript yard at #34 was the last residence of one of modern Chinese history’s most famous spies, Kawashima Yoshiko (1908-1948). She was born Aisin-Gioro Xianyu to an elite Manchu family in 1908 but was adopted and raised in Japan by the Japanese nationalist Kawashima Naniwa, who named her Yoshiko. By the 1920s, Yoshiko had returned to China where she became notorious for her behavior and a series of high-profile affairs with powerful men. It was also about this time that Yoshiko began a lifelong habit of dressing, speaking, and wearing her hair like a man. During the War with Japan, Yoshiko identified herself as a Manchu patriot and participated in a number of clandestine operations on behalf of the Japanese and the government of the puppet state of Manchukuo. It probably helped that the ruler of Manchukuo at the time was her cousin, the Emperor Puyi. Her exploits made her famous, but by the time she moved to Dongsi Jiutiao in the early 1940s, she was dealing with depression and drug addiction. She lived as a semi-recluse with her assistant Ogata Hachiro and her four pet monkeys. On October 11, 1945, her seclusion came to a brutal end, when the police barged through her door and dragged Kawashima Yoshiko out of her home. With a bag covering her head, she was hustled into a waiting car and driven a short distance to the Paoju Prison, located just east of Yonghegong. She was put on trial as a collaborator and traitor a month later. In 1948, she was executed in the Paoju Prison yard by a single shot to the back of her skull.

This rather nondescript yard at #34 was the last residence of one of modern Chinese history’s most famous spies, Kawashima Yoshiko (1908-1948). She was born Aisin-Gioro Xianyu to an elite Manchu family in 1908 but was adopted and raised in Japan by the Japanese nationalist Kawashima Naniwa, who named her Yoshiko. By the 1920s, Yoshiko had returned to China where she became notorious for her behavior and a series of high-profile affairs with powerful men. It was also about this time that Yoshiko began a lifelong habit of dressing, speaking, and wearing her hair like a man. During the War with Japan, Yoshiko identified herself as a Manchu patriot and participated in a number of clandestine operations on behalf of the Japanese and the government of the puppet state of Manchukuo. It probably helped that the ruler of Manchukuo at the time was her cousin, the Emperor Puyi. Her exploits made her famous, but by the time she moved to Dongsi Jiutiao in the early 1940s, she was dealing with depression and drug addiction. She lived as a semi-recluse with her assistant Ogata Hachiro and her four pet monkeys. On October 11, 1945, her seclusion came to a brutal end, when the police barged through her door and dragged Kawashima Yoshiko out of her home. With a bag covering her head, she was hustled into a waiting car and driven a short distance to the Paoju Prison, located just east of Yonghegong. She was put on trial as a collaborator and traitor a month later. In 1948, she was executed in the Paoju Prison yard by a single shot to the back of her skull.

x--x--x--x--x

In Beijing, Yamaguchi's classmates "had been working with total devotion for the resistance movement", while she had spent the summer of 1937 in "pleasurable diversions". Yoshiko came back to Beijing and "faced the reality of unrelenting anti-Japanese demonstrations and gatherings." These student gatherings caused Yoshiko a lot of grief, as mentioned above.

And then this astounding event occurs: "Two months before my graduation [most likely in 1938 - Ed.] from Yijiao Girls School, the school building was dynamited and demolished by an unknown party. The situation was getting increasingly unstable, and there would be no formal graduation ceremony."

x--x--x--x--x

During a memorable day-trip to the Summer Palace grounds, Yoshiko states "the Second Sino-Japanese War was becoming more ferocious, and increasingly my feelings about the conflict were threatening to tear my whole body apart. Having no idea what I would do after graduation, I was seized with an indescribable sense of anxiety about the future." In the main hall of a Buddhist temple, she and her classmate Wen Guihua pray. Yoshiko prays that the war would end soon and that "I would be enlightened with regard to how to live my life after graduation from the girls' school."

At this point in her memoir, Yoshiko uses a boat-ride across the Kunming Lake (picture below) to convey the momentous journey that she is about to make:

Accompanied by a hermit-like old boatman "who had once served as an attendant to the Empress Dowager" and who speaks in mysterious old Mandarin phrases, she recalls how radiantly the sun was setting against the backdrop of beautiful temples, pagodas, covered walkways, and gardens:

For one, the sun is not rising, it is falling beautifully out of the sky. Another was that the sun was setting on her time in Beijing as the high-school girl Pan Shuhua. It was setting on those innocent days spent in the Forbidden City as though she were a royal Chinese princess riding her horse through her private gardens.

The boat itself is a vehicle taking her to an opposite shore; the Summer Palace a destination that had "brought soothing comfort that day as it had done in the past." There will be other vehicles in her life, taking her to far shores, but this day marks the end of her school-girl phase of life and the beginning of the next.

The ninety year old boatman must have given the two Chinese princesses in his care a very good blessing indeed, because when Yoshiko returns home, two emissaries await her bearing a proposal for her to embark on the journey which will bring her world-fame.

x--x--x--x--x

Yamaga (the intelligence agent) and someone named Yamanishi (from the Manchurian Film Association) are on a recruiting mission and have been waiting for Pan Shuhua to return. They all go off to a fine restaurant in order to discuss business.

Yamaga leads off the conversation, explaining to Yoshiko that the Manchurian Film Association (Man'ei) was formed "to promote Japan's political objectives", ie, "Cooperation and Harmony among the Five Races" and "Japanese-Manchurian Friendship." He further tells her that "they wanted me to assist in that enterprise", because Man'ei could not find someone suitable who could sing. Yamanishi continues the subterfuge, asking "Well, how about it Yoshiko-chan? We are not asking you to appear in a film, just do a recording of its songs." Yoshiko "thought it wouldn't matter much if all they were asking was just for me to sing" and she "has nothing against singing itself."

It was in this way that Yamaga and Yamanishi secured Yoshiko's agreement to join the Man'ei operation in Manchukuo, which Japan had created in 1932. Almost fifty years later, in June 1985, Yoshiko visited Yamanishi at his home in Tokyo to reminisce about that past meeting and the slight-of-hand that was used to recruit her.

It was in this way that Yamaga and Yamanishi secured Yoshiko's agreement to join the Man'ei operation in Manchukuo, which Japan had created in 1932. Almost fifty years later, in June 1985, Yoshiko visited Yamanishi at his home in Tokyo to reminisce about that past meeting and the slight-of-hand that was used to recruit her.

Yamanishi candidly revealed that actually, Man'ei was seeking "A native Manchurian girl who could sing, speak Mandarin, and understand Japanese - that's why I became so eager to persuade you to take the job." Furthermore, he says Yamaga was the only one capable of convincing Li Xianglan to join Man'ei, and that the two of them had "colluded" together in not revealing the whole truth to her: "we had all along wanted you to appear in the entire film" and not just "to dub a few songs".

x--x--x--x--x

This chapter in her life had begun in May of 1934, when a nervous 14yr old Yoshiko had boarded the train to Beijing, "pretending to be Chinese" in the 'hard-seat' section. Now, she was going back home as a confident 18yr old, sitting in the same 'hard-seat' section, mingling and conversing with fellow Chinese passengers, as a Chinese, and not afraid to travel alone.

There is no way that Yoshiko, sitting there watching the countryside glide by, could ever have imagined the abrupt and total change her life would take with just one step off of that train car - from a schoolgirl with her hair tied in a bun wearing a plain blue cotton uniform, and instantly into a world of smiling waving 'fans' cheering her arrival, hanging on her every word, and chauffeur-driven cars, movie-making, and everything that came with it!

Imagine the scene then: a large number of people, including all the top-brass of the Manchurian Film Association were "feeling pretty fidgety at Xinjing Station" as they waited for their prize recruit:

Finally, the train pulls into the station and everyone rushes to the 'soft-seat' cars where the Japanese and upper-class Chinese usually sit, but no one they recognize gets off! Deflated, as they all wonder what happened to Li Xianglan, way off at the end of the station could be seen a plainly dressed short girl waving goodbye "to Chinese passengers leaning forward from the windows of their hard-seat car". [One wonders, which songs did she sing for them during the trip?]

The girl then turns to see this crowd of people so happy to see her and thinks to herself "why are all these people here to greet me if all I'm going to do is sing some songs?" The Man'ei top-brass can see in an instant how friendly and at ease this girl is with everyday Chinese people. They think to themselves "Yes! That's our girl! - Man'ei's Li Xianglan, beloved by the ordinary people of China, the birth of a star befitting the goals of 'Japanese-Manchurian Friendship' and Harmony among the Five Races!" The die has been cast.

x--x--x--x--x

The next morning, a car picked up Li Xianglan and took her "to a squalid place that appeared to be a film studio". She's sat down in front of a big mirror, whereupon some man crudely puts cream and makeup on her face until she resembles someone out of a Chinese opera (ie, very heavy makeup). Then they asked her to stand in front of a big camera, and strike posses, looking this way and that way, hold her head this way, now that way. "Smile, look sexy, open your mouth slightly", etc.

Meanwhile, Li is wondering when they are going to ask her to sing, and feels like she's "breaking down" because of the humiliation of posing and following precise orders with no regard for how she feels. It's only later that she realizes she's "been hoodwinked" into making a screen test that day.

You can imagine the delight of the director who was firing orders like some army officer at her; he probably couldn't believe his luck in finding this 'diamond in the rough' who could inadvertently smile one hundred different ways! They must have known instantly what they had.

Two days later, she's on a train bound for Beijing along with other actors and a large film-crew. The "silly comedy" (her words) of her first film involves the capers of a couple of newlyweds inside the sleeper car of a train traveling from Xinjing to Beijing (see below for details on this film). Trains at that time were like the internet is today: exciting and cutting edge technology. Li Xianglan's film career was in motion! And here is probably one of her first of many magazine covers:

Yoshiko's star rose quickly. In 1938 the below magazine showed her doing a variety of home-activities, designed to cheer up soldiers on the battlefield, who no doubt appreciated her femininity and beauty:

Yoshiko's star rose quickly. In 1938 the below magazine showed her doing a variety of home-activities, designed to cheer up soldiers on the battlefield, who no doubt appreciated her femininity and beauty:

Many of the below photos were probably taken after the 1938 year, but then again, I thought readers would appreciate them here anyway (someday I hope to organize them into a time-line, he said):

Ian Buruma's novel "The China Lover", describes Manchurian women thusly:

“The Mukden women were the most beautiful north of Shanghai: the Chinese girls, lithe and nimble as eels in their tight qi pao dresses; the kimonoed Japanese beauties, perched like finely plumed birds in their rickshaws bound for the teahouses behind the Yokohama Specie Bank; the perfumed Russian and European ladies taking tea at Smirnoff’s in feathered hats and furs.”

It is here that I'd like to express a personal opinion about the pure oriental beauty of Yoshiko's face. It is one of the most divinely beautiful, yet 'changeable' faces I have ever seen. So variable that at times she leaves you wondering "can this be the same girl?"

She has one of the most extraordinary live 'presences' in still photos that have ever been seen.

She seemed to have a different 'look' in every photo that was ever taken of her, and it was quite an effortless and natural beauty. Combined with her singing talent and charming personality, it is no wonder that she became a super-star and a beloved one at that: not just a vision of loveliness, but lovely in every way.

Even her pensive and moody expressions are beautiful:

The following video shows Yoshiko at about age 18 singing while sitting precariously atop a building in the New Capitol (or Hsinking, Xinjing or Changchun as the city is called today). The video is delightful, showing as it does a positive image of all the work and accomplishments of the (mainly Japanese) people who are waving at the camera. Then we see Yoshiko sitting on a big tractor and having a fun lunch with the field hands on a large farm. (That nudge and smile between the guys as Yoshiko is handing out fruits is part of that great universal language which everyone in the world knows.)

It's almost impossible to consider that this beautiful little film was made during the same period in which the Japanese army was committing the worst atrocities against the Chinese citizenry in places like Nanjing. What a mystery of 'the human condition'!

I guess you could also say that one man's "delightful video" is another man's "propaganda film", but the truth was that the Japanese government was using these images to promote Manchuria, the land of promise, to the poor masses of Japan people who's labor was sorely needed to develop the new land. Stories abound of how so many were misled into expecting tractors, nice houses, and fields of grain to the horizon, when in reality they were issued one cow or water-buffalo to manually till the soil, and often had the back-breaking chore of clearing the land while living in primitive conditions worse than what they had left behind in Japan. And always present were the actions of Chinese 'bandits', who didn't appreciate being displaced on their land by Japanese farmers.

What this means to me, is that history is not some simple story of 'good guys' verses 'bad guys', nor can it be summarized in just a few sentences (contrary to what government propaganda would have you believe). This is one of the reasons I decided to delve into Yamaguchi's life story in the manner you see here; I felt there was more to her story than what we were being sold (told) by media like the NY Times and the Washington Post - if what her films and the above short video shows is propaganda, then 'what the world needs now' is more of it!

Yoshiko's image was used in the many brochures extolling the positives that came out of Manchukuo during this time. Here's one such magazine.

this next video (with jazz-music of the time) shows how those buildings in Changchun were actually built (by real people, ie Japanese and Chinese, etc):

other Chinese sites which feature the same video:

or:

Some people refer to this type of architecture as "fascist architecture", which is ill-advised considering the obvious beauty and longevity of these buildings. They have given Changchun among other cities it's present unique character; what do tourists come to see, the drab factories? no, they want to see real character as reflected in the beauty of real Manchukuo architecture. People who try to poke fun at this architecture are missing the point right under their noses: these buildings have character and longevity.

For those who want to see what the new capitol Xinjing (now Changchun) looked like in the 1930s with all the massive Japanese construction projects and wide european type boulevards, here are two videos that convey it very well:

but thats not all you get - there are the 'old town' Chinese areas also:

x--x--x--x--x

In 1938, the Manchurian Film Association (Man'ei, based in Xinjing, the New Capitol of Manchukuo) coerced Li Xianglan to act in the film Honeymoon Express [as in express-train]. They told her she would only be singing and would not have to do any acting. At the time of her first screen test:

candid snapshots pasted in someone's scrapbook:

a lovely genuine smile from the beginning stage of her career:

She states that her whole first film experience was humiliating, embarrassing and miserable - she had no training in acting and was forced to make a fast transition from innocent school-girl to dolled-up newly-wed whispering sweet nothings in her (comedic) husband's ear! It was a harsh introduction to the real world of film production from the school-girl life of privilege she had led in Beijing, and required a fast transition from innocence to adulthood.

They had to film in freezing conditions in a primitive train shed while a new studio building was being built. In the winter, the temperature would drop to minus five degrees Fahrenheit inside the shed. The equipment had to be heated over an old coal stove before they could start shooting.

The film-director would scold her, screaming "That's all you can do? just get out of my sight!" After work, she'd go cry alone in her hotel room. She vowed to herself this would be the last film she ever made!

She sang the hit song "We Are Young", (music composed by Masao Koga) a love song for newlyweds, while on a train running from Xinjing to Beijing:

You hear the 'call and response' in this song as Yamaguchi says:

When I called you 'My dear', you answered,

'Yes, my dear?'

The echoes from the hills ring with joy My dear!

'Yes, my dear?'

The sky is blue, and we are young!

She got through the movie by 'gritting her teeth', expecting it to be her last such endeavor. However, unbeknownst to her, Man'ei (the film company) had already signed a contract with her parents, so the die was doubly cast.

various stills from Honeymoon Express, her first film:

Following this movie, in 1938 she made two other movies in quick succession: "The Spring Dream of Great Fortune" and "Retribution of the Vengeful Spirit". These three films "were all experiments" involving different story styles.

below, from another film titled "Blood of Arms and Heart of Wisdom": Yoshiko is the second girl from the right:

Throughout her association with Man'ei, she was entertaining Japanese troops (because that was what top-stars were obligated to do). Her biography makes no attempt to hide or obfuscate it; this next photo was taken in November 1938:

throughout this phase of her life, the Japanese military were in the background.

throughout this phase of her life, the Japanese military were in the background.

In the beginning, her lodgings were quite spare, but eventually Man'ei paid Li Xianglan very well (about 6x what other Chinese actors received) and she didn't have to live in a dormitory as the other actors did. Her pay was 4x that of a college graduate working in Japan.

At the hotels where she lived, and when she traveled, a chauffeured car was always provided for her personal use (you can find an account by her personal chauffeur of what she was like, at the bottom of this page) one of the cars pictured below may be the very-same Ford he owned:

Her coworkers suspected she was either full Japanese or of mixed-blood, especially after they noticed her speaking Japanese to her 'attendant', Masako Atsumi. But even so, everyone got along fine and shared a camaraderie, mainly because Yoshiko was such a friendly person. Forty some years later, when she went back to meet them, she states "they were all wonderful people" - "we belonged to the same generation and spent the spring of our youth together."

x--x--x--x--x

The next pictures were taken during her 1939 visit to celebrate the Greater East Asia Construction Exposition held in Osaka. Here are some news photos taken of this huge event which lasted a couple of weeks (Yoshiko performed songs twice a day). Arriving at Tokyo Station:

the person on left is Toshiko Sekiya, a highly-educated international opera star. She and Yoshiko had the same voice coach (Miura Tamaki). Sekiya's brief life tragically ended in 1941.

in the next series of pictures below, she was chosen to be an "ambassadress" from Manchukuo, a great honor for her and Meng Hong:

Please note the high-collared Chinese dress she is wearing (few of her pictures from this phase of her career show her in typical Japanese dress). To me, the above picture is significant because she is telling the sold-out crowds of thousands of fans: "I am not your typical Japanese girl, I'm Manchurian born and bred, and I'm my own person".

When she would walk around Tokyo wearing the same type qipao (cheongsam) dress, she notes in her memoirs the racist and demeaning 'Chankoro' comments which were made, and this was a new and sad experience for Yoshiko (much like the unpleasant encounter she had with a ship's policeman while coming to her 'ancestral' country – story below).

According to accounts of the time, Chinese songs were popular in Japan, as they are even today. A lot of the most loving videos of Li Xianglan on YouTube today have been made by her Japanese fans, although they use the name "Ri Koran" which is the Japanese pronunciation of Li Xiang Lan: 李香蘭

Another picture from the same series of concerts (the two fellows on the left are comedians (perhaps Japan's version of Abbott and Costello) and the girl on the right is Yoshiko's good friend Meng Hong:

below, at a 1939 show:

1938 - First visit to Japan

In her later memoirs, Xianglan recalls her first visit to Japan in 1938: the first leg of journey from Fengtian to Pusan, Korea: (thanks to Japanese blogger Yanagi470 for this series of pictures - Ed: Yanagi and myself apparently have the same impulse to write and post pictures about Yoshiko's life):

"yes, it was on the [ferry] boat between Pusan and Shimonoseki", left side of below map:

one of the ship's policemen said - "Aren't you ashamed, wearing Chankoro (Chink) clothing like that and speaking that Chink language?" and "If you're a subject of the Japanese empire, speak Japanese!"

she then says:

"When he said that, I didn't say "I'm Japanese". I took those words as if I were Chinese. Having such experiences, I grew to hate [those] Japanese people. What a nasty group of people, I thought, with their blatant feelings of superiority and prejudice against Asian people."

Please note the "I took those words as if I were Chinese". To me, this 'says it all' about what she thought of herself. And there are many instances in her memoirs that recount similar sentiments - of a young person who considered herself to be Chinese, and of other people around her who also considered her to be Chinese (or at least half Chinese). Later, in the addendum to her memoir, she would say "spiritually, I was a mixed race child between China and Japan". It's clear that emotionally and intellectually she considered herself Chinese during this time period. [left photo below is from 2019 Asahi Shimbun]

"On that same visit, I participated in the Exposition for the Founding of Manchukuo as a representative of Man'ei. For promotional events at the exposition and at the Nichigeki Theater, I sang wearing a Chinese dress. There too, I directly experienced the disdainful gaze that was directed at 'Chankoro'."

What a great disappointment - to finally reach your ancestral country that you've longed to see, only to experience racial prejudice and be publicly scolded!

It's clear from the above comments that Yoshiko was hurt by Japanese attitudes towards Chinese and later she says that Chinese denigration of Japanese also hurt her - it is something she says she emotionally never fully recovered from, "that two countries who should be the closest of friends, were at war" (another way she phrased it, was that 'people with black-hair and black eyes should not be fighting one another').

As an idealistic young person, she misjudged the level of hatred between China and Japan and how it would be directed at her in the near future. As a young woman "she considered China her home country and Japan her ancestral country. She had always loved them both, she told The Boston Globe in 1991, and never fully recovered from the war between them. “The war, in my mind, is never over,” she said. . . By making the comparison of China as her motherland and Japan as her fatherland, she was saying it felt like the two parents were killing one another in the war.

x--x--x--x--x

|

Yoshiko says "at the beginning, acting in front of a camera was so embarrassing that I wanted to cry. But once I got used to it, the exercise became sufficiently interesting that I was inspired to take an active initiative in studying acting." You might look at this last statement as an example of how her lively spirit can be somewhat 'lost in translation'; unfortunately this happens frequently in her memoirs.

This is why the live performance she gave in 1950 is so important - it shows what a 'full of life' bright spirit and energetic entertainer she actually was.

And since she was the type that became "totally engrossed in whatever she did," this meant taking lots of lessons and classes that Man'ei sponsored for it's stable of actresses below:

the woman at top left of below picture is the beautiful actress Li He, Yoshiko is directly below her:

Yoshiko is on the far right of above picture.

Construction of the new studio building in Changchun was finished in spring of 1939, it was "the largest in Asia", had state-of-the-art equipment, and was a sophisticated facility, greatly boosting everyone's morale who worked there:

below, as it looked during Yoshiko's visit in the 1990s:

The history of the Manchurian Film Association (Man'ei) is quite interesting, involving as it does a former right-wing militarist named Masahiko Amakasu who was appointed as managing director. He's an example of someone who has a rigid militarist past, who apparently 'sees the light' (or perhaps decides to 'make amends' for past murderous deeds) when he becomes the head of Man'ei in 1937.

He emigrated to Manchuria in the late 1920's after serving jail time in Japan for his involvement in the murder of several anarchist political opponents. It seems he then participated in 'behind the scene' intrigues such as the 1931 Manchurian Incident (which had the effect of launching Japan's militarists into northeastern China), the Tianjin riots, and other schemes involved with installing the last Qing dynasty heir named Puyi as 'emperor' of the new country of Manchukuo.

However, you could almost say he became something of a 'Manchurian nationalist' when dealing with his home country of Japan. As one reads about the actions of various key people (both Chinese and Japanese) in the history of Manchuria, it appears there indeed was a belief in the nascent 'new country' which was not just propaganda. It is easy to parrot the phrase "puppet government", but as Masahiko demonstrated, at times the puppet had a life of it's own.

Yoshiko says that Xinjing's Japanese community was quite concerned about an ex-militarist being appointed manager, fearing his authoritarian influence. But, according to several accounts, he becomes a good leader for Man'ei (ie, raising everyone's wages, improving the working conditions, acquiring the latest equipment, employing many talented film-people without regard to their race or political views) and really followed his own path rather than one handed down from Japan's military authorities.

At the risk of spoiling a good story, I've decided to jump ahead in time, as Yamaguchi does in her memoirs. Regarding Masahiko Amakasu: while the Soviet army was entering Xinjing in late August 1945 at time of defeat of Japan, Masahiko took potassium cyanide and died. He remained true to his own code of honor to the Emperor.

x--x--x--x--x

in 1939 Yoshiko also worked on the film "The Monkey's Journey to the West", which was based on a traditional Chinese folk-tale. Here is a snippet of the film:

x--x--x--x--x

At Man'ei, classes were given in acting, "practical skills", Chinese classics and poetry, martial arts, the er'hu (Chinese violin), classical dancing, Western ballet, etc. There were also light moments, such as this one where Meng Hong and Yoshiko are playing with rabbits:

At times, Xianglan would play the piano to accompany the Man'ei lecturer. Whenever she had spare time, it was up to the third floor rehearsal room to practice piano and voice lessons. A group photo of Man'ei people taken in Taiwan:

Li Xianglan was by far the hardest worker, continuing to take voice lessons until stopping her film career in 1958 (and maybe after also). She had notable voice teachers in every major city (Fengtian, Beijing, Shanghai, Tokyo, New York) and her voice progress through the years can be heard in her many recordings.

I don't think enough credit has been given Yamaguchi for her achievement in rising to the 'top seven' rank of Shanghai divas. The competition was fierce and also beautiful:

And when you add in the fact she was successful in both the Chinese and Japanese markets, it was a remarkable achievement.

Here is a rare short clip of Yoshiko singing with small orchestra in 1938.

x--x--x--x--x

Her next film in 1939 would be "Travels to the East", the story of two Manchurian 'bumpkins' who go on a sightseeing tour in Tokyo. "The aim of the film was to introduce Japan to Manchuria's Chinese audience." but it also served the reverse purpose:

Then came "Blood of Arms and Heart of Wisdom", about police who expose the activities of a group of smugglers. One of the scenes involved the police cavalry chasing a horse-riding gang. Man'ei used actual race-horses loaned from a local Anshan race-course for the scene; Yoshiko had a good laugh watching the men fall off their steeds, since she well knew how to ride from her days with the Pan family, riding through the Imperial gardens in Beijing.

This next photo is not of Yamaguchi, but it's so exuberant and perfect that I thought it might convey how Japanese film loves to portray horses, men, women, etc:

by coincidence, the actor on the right is Toshiro Mifune, who was also born in Manchuria, and also in 1920! He made several films with Yamaguchi, starting with the 1950 film Scandal.

here is what Akira Kurosawa said of him:

Remembering their earliest work together, Kurosawa later wrote of Mifune in his autobiography:

"Mifune had a kind of talent I had never encountered before in the Japanese film world. It was, above all, the speed with which he expressed himself that was astounding. The ordinary Japanese actor might need ten feet of film to get across an impression; Mifune needed only three. The speed of his movements was such that he said in a single action what took ordinary actors three separate movements to express. He put forth everything directly and boldly, and his sense of timing was the keenest I had ever seen in a Japanese actor. And yet with all his quickness, he also had surprisingly fine sensibilities."

Those Manchurian-Japanese actors . . . . it must be the air . . .

here is what Akira Kurosawa said of him:

Remembering their earliest work together, Kurosawa later wrote of Mifune in his autobiography:

"Mifune had a kind of talent I had never encountered before in the Japanese film world. It was, above all, the speed with which he expressed himself that was astounding. The ordinary Japanese actor might need ten feet of film to get across an impression; Mifune needed only three. The speed of his movements was such that he said in a single action what took ordinary actors three separate movements to express. He put forth everything directly and boldly, and his sense of timing was the keenest I had ever seen in a Japanese actor. And yet with all his quickness, he also had surprisingly fine sensibilities."

Those Manchurian-Japanese actors . . . . it must be the air . . .

x--x--x--x--x

Summary thoughts on the 1937 phase of Yamaguchi's life, by John M.

Yoshiko's 'managers' (if we may call them that) such as Toru Yamaga, were intimately knowledgeable about the development of a Chinese-born girl into the Japanese woman-warrior named Yoshiko Kawashima (after all, Yamaga was her first lover). So it was no coincidence that having noticed and nurtured the young Yamaguchi, they would bring these two bright sparks together just to see what would happen and how one might influence the other.

And so, in one of life's stranger than fiction situations, these two fascinating women who were both Chinese and Japanese (one a 17yr old ingenue and the other 30yrs old, wounded in body and soul) met one another in Tianjin. Yes, they were allured by one another and probably danced together . . Westerners (some with Puritan ethics overlain by porn-addled imaginations) might never understand that oriental girls holding hands and dancing, or Arabic men holding hands while strolling, or Russian leaders embracing and kissing each other on each side of the face, or European tennis-players who have fought for five hours and end up in a sweaty embrace at the net, do not imply anything at all about their sexuality while they are doing something which to most people of the world is very human.

Judging from the tone of her memoir, Yamaguchi was indeed enamored with Kawashima in the beginning of their relationship, but came to realize she did not want to be a follower or an associate of Kawashima. This was important, because her sense of danger (that her friend Kawashima had to be avoided) eventually saved her life. This was because during the trial in late 1945, both Yoshikos were jailed (one in Beijing, the other in Shanghai) and accused of being traitors. Even the newspapers of the time claimed that both Yoshikos (as well as Tokyo Rose!) would be executed. And indeed, in 1948 Kawashima was executed by means of a bullet to the back of her head.

Yamaguchi specifically tells us that Kawashima "only gave me two Chinese dresses" mentioning that this was a point of contention during the trial. Since we don't have any trial proceedings, it's possible that Yamaguchi was forced to renounce her friendship with Kawashima; perhaps this is part and parcel of the 'great guilt' that Yamaguchi felt regarding these years. Remember that in another of those 'made for a movie scene' episodes, Kawashima secretly enters Yamaguchi's hotel-room and leaves her a long, revealing, and heart-rending letter, specifically warning Yamaguchi to avoid the fate of being 'treated like garbage' when the party was over with Japanese militarists.

. . and perhaps her 'managers' wanted to give Yoshiko a taste of the 'good life' to see whether she had any weaknesses of character that could be exploited. If Yoshiko at age 34 and arriving at Tokyo airport was so fun-loving and uninhibited as to end up laughing in the rain while being lifted off the ground by Robert Stack . . . well you can just imagine how energetic and playful she must have been at age 17!

Has any critic yet (such as Wang, Stephenson, or Buruma, et al) ever mentioned how beckoning it would have been for a pretty and vivacious young girl in the social milieu of that time to have been side-tracked into an easy life as a high-priced consort to the drug-addled aristocracy, a rich-man's wife or mistress, or a war-lord's concubine or a night-club denizen singing and dancing her life away - alas, this was the fate of many girls who did not have the talent, focus, and personal fortitude that Yamaguchi had. In her time here on earth, she never succumbed to the easy life.

In any case, the far-seeing, open-eyed Yoshiko Yamaguchi in her little boat somehow managed to come through all the life-threatening shoals of her late teenage life.

to be continued:

No comments:

Post a Comment