HAPPY BIRTHDAY YOSHIKO! FEB 12, 1920

After much consideration and years of work in assembling all the various information contained on this website, I would like to offer the reader some further thoughts and insights about Yoshiko's life which they may find surprising. First, some general comments:

Concerning how I have written this history of Li Xianglan, I've decided not to revise my earlier opinions and assessments written over several years time (such as are on the 1920-1933 page) based on new discoveries (unless matters of fact are involved). This means the reader will find contradictions throughout the website, however, this page you are reading contains my latest thinking on the subjects presented.

So let us begin with Yoshiko's early life: in her 1987 memoir: Yoshiko already reaches the age of 12 (1932) by page 6 in the English translation (page 3 in the Chinese and Japanese editions), ie, she speeds through her early years as if they didn't really matter that much. And in these first pages, she never mentions the names of her siblings. However, she does mention her two best friend's names and the 'little society' they formed. Yoshiko does not even name all the people in her family group-photos (or give us the year the photos were taken). One wonders why there are no recollections, vignettes, favorite episodes, or childhood escapades, etc. specifically involving family members. Were there no warm memories of her childhood family life? Yoshiko never says things like “I got this trait (or that talent) from my mom, or dad”, or "my sister was also good in Chinese" or "so-and-so fell into a mud puddle while we were playing" or "one of my sisters contracted polio". In none of the many editions of her memoir will you find any photos of her and any of her sisters/siblings just having fun or on an outing somewhere, and this adds to the general feeling I expressed above.

Ok you say, maybe she just wanted to speed through these early years: but then wouldn't you expect someone in the Yamaguchi family (over the next 80 years or so, 1940 - 2020) to reveal some small heartwarming detail or story like "My famous sister (or Aunt) - what life was really like" or "Growing up with the super-star who always forgot her lunch" or some similar memory?

The sum total of all the above possibilities for the family to have said something is almost zero. But this silence of the family also includes Yoshiko: outside of the few pictures and glimpses of the family we get from her memoirs, Yoshiko herself apparently never published or revealed anything much further about the Yamaguchi family. I have found no article or photo showing any family member after the below fascinating 'mystery' photo taken in a Buddhist temple circa 1939 (and believe me, I have looked for them!).

The only such instance where we even see a sibling is the post-decease 2015 TV program presented by Nikkei Business which featured Yoshiko's youngest sister Seiko. Until recently, the YouTube police had taken it down. A screen shot of Seiko is shown.

The only such instance where we even see a sibling is the post-decease 2015 TV program presented by Nikkei Business which featured Yoshiko's youngest sister Seiko. Until recently, the YouTube police had taken it down. A screen shot of Seiko is shown.

However (and this is a recent development), other people outside the family are starting to write down their memories (especially as they are now all in advanced age). Here are two such memory-accounts: one by a Taiwanese man who lived and worked in Shenyang during the 1938-1948 period, and the other by someone named Miyake who was Yamaguchi's classmate (although in a higher grade) in the same elementary school she attended. In this classmate's account, he recalls that everyone thought she was Chinese and when she started singing on radio, the whole school would adjourn to the schoolyard and all clap and cheer after her performance was over. (Ed: still trying to get a better translation of this source).

Her adoptions by the Li family in Mukden and the Pan family in Peking: The full significance of a Japanese family allowing their oldest daughter to attend Chinese rather than a Japanese school and to join not one, but two other Chinese families has been overlooked by history. My sense is that no Japanese family of that time period would've allowed a biological daughter to be 'passed off' to Chinese families like this. As the eldest daughter, she would've been essential to her mother in caring for all the younger siblings. Given the complex cultural web of duty and honor which strongly enmeshes a Japanese child, I feel it is highly unlikely that a biological 14yr old daughter would be sent off to parts unknown, even if the ostensible reason was to further her education. Add to this the fact that by 1934, it had already become dangerous for Japanese people to travel in China.

Where was the concern about Yoshiko's safety in strange households? - yes, you may trust the god-father of your 14yr old daughter, but what about the other males in a 100 person labyrinthine compound of many houses? - this was a time in history where an unattached female was 'fair game' and a time when 15yr olds became concubines of powerful men. In my research on Manchuria, I have not come across similar adoption stories, so the Yamaguchi adoption seems implausible [the Kawashima adoption not having complete similarity].

In 1937 her father Fumio accompanied Yoshiko to Tianjin to meet the famous woman-warrior Kawashima (who by this time had become something of an embarrassment to the Japanese military). It must have been known by Japanese authorities that Kawashima was leading a fairly debauched existence (addicted to drugs, awake all night and asleep all day, surrounded by a 'palace-guard' of young beautiful girls, hangers-on, drug-addicts, etc), and yet the decision was made to introduce Pan Shuhua (ie, our Yoshiko) to her. Would a loving father approve of this meeting, personally accompany her there, and leave his 17yr old daughter almost unchaperoned for her summer vacation in this degenerate situation?

Furthermore, we have what appears to be a daring photo (considering social norms at the time) of a bare-shouldered Yoshiko, perhaps taken at a swimming facility. In her memoir, she admits to sowing some 'wild oats' during her 1937 summer. Although we don't know the date of the photo, it is yet another example of the mystery, daring, and stunning allure of Yamaguchi.

Many of Yoshiko's films reflect or reprise actual elements of her real life.

Another film containing elements of her real life story is the 1952 "Woman of Shanghai" reviewed in "The Attractive Empire" by Michael Baskett. He writes the film "was a fictionalized film biography of Yamaguchi" and "obvious parallels with Yamaguchi's own life can be found" in it.

Yamaguchi's memoir states "I was born in the suburbs of present-day Shenyang". But her signed 1950 visa application shows Place of Birth as "Bujun". Granted, this name is close in Chinese pronunciation to "Fushun" and perhaps this is only a minor issue:

John M. theory about Li Xianglan/Yoshiko Yamaguchi origin.

1. Her birth-name was Li Xianglan. She was not a 100% biological Yamaguchi (if indeed she had any percentage at all). Her exact parentage is unknown at this point in time, but perhaps her quote "China is my motherland, Japan my fatherland" is a big clue.

1. Her birth-name was Li Xianglan. She was not a 100% biological Yamaguchi (if indeed she had any percentage at all). Her exact parentage is unknown at this point in time, but perhaps her quote "China is my motherland, Japan my fatherland" is a big clue.

At her birth, someone looked down at her perfectly formed baby face and said "what a sweet flower you are!" and presciently named her Xiang Lan (or fragrant orchid). She may have been a foundling from a war-zone, or because of her surname Li, more likely a daughter of Li Jichun or a relative in his extensive household and an unknown mother, possibly Japanese (possibly from the Ishibashi clan - ie, mother's side - both Aiko (a beauty in her own right) and Yoshiko were quite short in stature whereas Fumio was tall).

Li Jichun was a major participant in the warlord military history of north and east China during the 1912 - 1945 period and especially during the founding of Manchukuo.

9. Finally, I believe it is a western intellectual misconception (or a conceit) to label Yamaguchi as basically a deceptive Japanese person, when in fact she clearly exhibited characteristics of both cultures and hence may have been genetically mixed. Her extraordinary life-story is a fascinating example of human complexity, resilience, and survival, rather than one of just being a simple 'made for TV' masquerade. The typical western scholar's propensity to use 'jargon' and 'buzzwords' when analyzing Li Xianglan has the effect of obscuring rather than revealing her life. The mental gymnastics that these people engage in while trying to judge Yoshiko's life-story by modern politically-correct gendered studies is something to behold.

As we gaze at this last exquisite image of the teenage Li Xianglan, dressed in Chinese brocade and autographed with her Chinese name, let us consider the obvious possibility I propose. My final assessment of all the circumstantial evidence leads me to strongly suspect that a baby named Li Xianglan (subsequently named Yoshiko Yamaguchi) was legally adopted at an early age by the Yamaguchi family: she does not appear to be 'of this family' even though she was raised and beloved by it. She has stated in her memoirs that it caused her a lifetime of pain.

Concerning how I have written this history of Li Xianglan, I've decided not to revise my earlier opinions and assessments written over several years time (such as are on the 1920-1933 page) based on new discoveries (unless matters of fact are involved). This means the reader will find contradictions throughout the website, however, this page you are reading contains my latest thinking on the subjects presented.

It has always seemed to me that Yoshiko's singing goes beyond ideology, straight to the depths of one's heart and conveys a poignant sadness beyond words (particularly her Suzhou Serenade, or Soshu Yakyoku). Many of her pictures also convey a wistfulness to me. Her memoir is a gold-mine of historical data and information about her life, both for what she says and what she does not say. I believe she knew more than she revealed she knew; this is certainly not the equivalent of saying "she did not tell the whole truth". Furthermore, I think she experienced more than she revealed she experienced, and this included the good, the bad, and the ugly aspects of life.

x--x--x--x--x

With the above generalities out of the way, I will preface my particular thoughts with this famous 1957 quote from Hong Kong Shaw Brothers movie-publicity: ". . . she is as mysterious as the fog. Is her real name Yamaguchi Yoshiko or Li Xianglan? Is she Japanese or Chinese?". This is a very significant statement because it confirms what most Chinese and Japanese people were thinking (the Shaw Brothers were very astute businessmen and in-tune with their society). Everyone had questions about this fascinating mystery at the time. However, when we read Western academic work on her, this mystery is completely absent the discussion, and it is an interesting question why this is so.

Another question concerns why Yamaguchi felt it necessary to have someone else (ie, Fujiwara Sakuya) write her biography along with herself. She would have been quite capable of authoring her own biography given her language proficiency and diplomatic experience. Fujiwara was born in 1937 in Japan and spent his early years there; his family emigrated to Manchuria in about 1941 and narrowly escaped being killed in the Soviet attack of August 1945 (see the above link for further biographic information). As a proficient word-smith. he became a news-reporter and at times was based in the United States and Canada. Surpringly, he also became a Bank of Japan representative, and even delivered erudite lectures on the financial system.

So let us begin with Yoshiko's early life: in her 1987 memoir: Yoshiko already reaches the age of 12 (1932) by page 6 in the English translation (page 3 in the Chinese and Japanese editions), ie, she speeds through her early years as if they didn't really matter that much. And in these first pages, she never mentions the names of her siblings. However, she does mention her two best friend's names and the 'little society' they formed. Yoshiko does not even name all the people in her family group-photos (or give us the year the photos were taken). One wonders why there are no recollections, vignettes, favorite episodes, or childhood escapades, etc. specifically involving family members. Were there no warm memories of her childhood family life? Yoshiko never says things like “I got this trait (or that talent) from my mom, or dad”, or "my sister was also good in Chinese" or "so-and-so fell into a mud puddle while we were playing" or "one of my sisters contracted polio". In none of the many editions of her memoir will you find any photos of her and any of her sisters/siblings just having fun or on an outing somewhere, and this adds to the general feeling I expressed above.

Ok you say, maybe she just wanted to speed through these early years: but then wouldn't you expect someone in the Yamaguchi family (over the next 80 years or so, 1940 - 2020) to reveal some small heartwarming detail or story like "My famous sister (or Aunt) - what life was really like" or "Growing up with the super-star who always forgot her lunch" or some similar memory?

To my knowledge, only one person in the Yamaguchi family (or the Li or Pan family) has ever made any public statement about their famous sister (or daughter, or relative): Seiko, the youngest child of the Yamaguchi family appeared in two separate interviews after the passing of Yoshiko (see link below).

This is strange: one would think that such great public interest in Yoshiko's life-story would have encouraged someone (anyone!) in these 3 families to at least write or say something: a letter to a newspaper, a communication with an academic, a remembrance by a grand-child, a radio interview: anything that could corroborate details, satisfy public curiosity, and add to our knowledge about her life. The lack of any such info from these families speaks loudly given the importance of family in oriental culture.

Photos of Yoshiko's first marriage, a very public event (to Isamu Noguchi, in Tokyo) contain no Yamaguchi family members; I believe this contradicts Japanese familial tradition. In a normal family of a famous personage, you would expect one or two members to have appeared either alone or with Yoshiko somewhere, possibly in some newspaper photo or gossip column in a film (eiga) magazine. There isn't even 'hearsay', ie, of the type "sources told us her mother said . . ."

The sum total of all the above possibilities for the family to have said something is almost zero. But this silence of the family also includes Yoshiko: outside of the few pictures and glimpses of the family we get from her memoirs, Yoshiko herself apparently never published or revealed anything much further about the Yamaguchi family. I have found no article or photo showing any family member after the below fascinating 'mystery' photo taken in a Buddhist temple circa 1939 (and believe me, I have looked for them!).

If any of my readers can elucidate what is occurring in this photo, please let me know. We see Yoshiko at the center of the photo with father to her right and mother seated to her left. If I recall correctly, a Pan family son is seated (he had joined a religious order); standing next to Yoshiko is her sister (who I think contracted polio, as recounted in an intelligence file). Is it possible that the ceremony shown in this photo represented the formal adoption of Yoshiko into the Yamaguchi (or the Pan) family?

The only such instance where we even see a sibling is the post-decease 2015 TV program presented by Nikkei Business which featured Yoshiko's youngest sister Seiko. Until recently, the YouTube police had taken it down. A screen shot of Seiko is shown.

The only such instance where we even see a sibling is the post-decease 2015 TV program presented by Nikkei Business which featured Yoshiko's youngest sister Seiko. Until recently, the YouTube police had taken it down. A screen shot of Seiko is shown. [recently a great friend of the blog located another TV show featuring Seiko as well as several other noted contemporaries of Yoshiko. They all revealed interesting anecdotes about Yoshiko as will be noted further in this essay.]

I find all the above-noted silence (over 80 years!) from the family incongruent, and an indication of just how estranged/distant Yoshiko and the Yamaguchi family may have been. Another possibility might be that the family is hiding something and has taken extraordinary steps to keep themselves out of the public eye.

I find all the above-noted silence (over 80 years!) from the family incongruent, and an indication of just how estranged/distant Yoshiko and the Yamaguchi family may have been. Another possibility might be that the family is hiding something and has taken extraordinary steps to keep themselves out of the public eye.

However (and this is a recent development), other people outside the family are starting to write down their memories (especially as they are now all in advanced age). Here are two such memory-accounts: one by a Taiwanese man who lived and worked in Shenyang during the 1938-1948 period, and the other by someone named Miyake who was Yamaguchi's classmate (although in a higher grade) in the same elementary school she attended. In this classmate's account, he recalls that everyone thought she was Chinese and when she started singing on radio, the whole school would adjourn to the schoolyard and all clap and cheer after her performance was over. (Ed: still trying to get a better translation of this source).

We have many photos taken in Yamaguchi's Tokyo apartment living room (she lived in this spacious apartment for about 20 years). Hanging there are artworks and photos of all the famous people she associated with. None of these photos show the Yamaguchi family or any family members (although yes, they could have been put up elsewhere), but no interviewer ever mentions seeing a family photo in her apartment. (the disparaging remarks of Prof. Yomota confirm that he noticed no family photos in her apartment which "he visited frequently in the early 90s").

Of all the interviews she granted in those last years, none mentioned the presence of any other person with Yoshiko except for an elderly 'amah' maid and care-giver; the family was non-existent and obviously not protective of her in the least.

Several sources do mention how lonely a life she leads towards the end, being wheelchair-bound and not leaving her residence in the final two years. One source says that after a final stroke, life-support was terminated and her body was cremated along with two of her favorite photos: (one of her taken with Charles Chaplin, the other with Margaret Thatcher).

The family had a 'spokesman' who barely spoke anything to the media following her demise, and has been silent since. Whereas other famous actresses and songbirds from her generation have received proper (and even elaborate) grave-sites, no such respect has been accorded Yoshiko. These appear to be the actions of an uncaring (or even spiteful for burning her photos) family. The implications of all the above points are clear: was there even a familial sibling and parental relationship here?

Of all the interviews she granted in those last years, none mentioned the presence of any other person with Yoshiko except for an elderly 'amah' maid and care-giver; the family was non-existent and obviously not protective of her in the least.

Several sources do mention how lonely a life she leads towards the end, being wheelchair-bound and not leaving her residence in the final two years. One source says that after a final stroke, life-support was terminated and her body was cremated along with two of her favorite photos: (one of her taken with Charles Chaplin, the other with Margaret Thatcher).

The family had a 'spokesman' who barely spoke anything to the media following her demise, and has been silent since. Whereas other famous actresses and songbirds from her generation have received proper (and even elaborate) grave-sites, no such respect has been accorded Yoshiko. These appear to be the actions of an uncaring (or even spiteful for burning her photos) family. The implications of all the above points are clear: was there even a familial sibling and parental relationship here?

x--x--x--x--x

The lack of basic information on her family leads to further questions such as: (1) was Yoshiko the only child who received father's tutoring in Chinese, (2) were her other siblings also given Chinese names? (3) was Yoshiko the only Yamaguchi attending Yong-an Elementary School? (4) were other of her siblings or friends also adopted into Chinese families? the lack of information in her memoir is telling in my view, and her omission in effect tells us the answers to these and other questions. [Note: the recent 2019 memorial Asahi Shimbun digital site has photo #116 on which Yoshiko comments that indeed, she was the only child in the family studying Chinese language.]

Given the tonal complexity of the Chinese language, there is great question in my mind as to whether a non-native speaker (ie, her father Fumio) could have given her the proficiency in Chinese which made her career possible. In a TV movie it is believable that "Fumio taught Yoshiko how to speak Chinese" but in real life it is superficial to think you can learn to speak Mandarin from a non-native father. You need total immersion in Chinese culture to speak like a native. Perhaps linguists can investigate this matter further someday and confirm what I'm saying here.

Her adoptions by the Li family in Mukden and the Pan family in Peking: The full significance of a Japanese family allowing their oldest daughter to attend Chinese rather than a Japanese school and to join not one, but two other Chinese families has been overlooked by history. My sense is that no Japanese family of that time period would've allowed a biological daughter to be 'passed off' to Chinese families like this. As the eldest daughter, she would've been essential to her mother in caring for all the younger siblings. Given the complex cultural web of duty and honor which strongly enmeshes a Japanese child, I feel it is highly unlikely that a biological 14yr old daughter would be sent off to parts unknown, even if the ostensible reason was to further her education. Add to this the fact that by 1934, it had already become dangerous for Japanese people to travel in China.

Where was the concern about Yoshiko's safety in strange households? - yes, you may trust the god-father of your 14yr old daughter, but what about the other males in a 100 person labyrinthine compound of many houses? - this was a time in history where an unattached female was 'fair game' and a time when 15yr olds became concubines of powerful men. In my research on Manchuria, I have not come across similar adoption stories, so the Yamaguchi adoption seems implausible [the Kawashima adoption not having complete similarity].

As Eri Hotta frankly mentions in her 2007 book Pan-Asianism, and John Dower confirms in War Without Mercy, the typical Japanese attitude in Manchukuo was that they were a higher class of people (after all, they had been the one oriental country who westernized first, had fully adopted the scientific and political ideas of the west, and had beaten both China (1895) and Russia (1905) with a westernized military). Yamaguchi's memoir itself gives us the best example of this superiority in the character of the policeman on-board the Pusan-Shimonoseki ferry checking her passport, who famously curses her up and down for using a Chinese name, wearing a Chinese dress, and speaking in Chinese while actually being Japanese. So what I am saying here is that her parents Fumio and Ai were people of their time, and I now doubt they would've been so idealistic as to give their own daughter over to another culture. However, if Yoshiko were not their real daughter, her leaving the family and 'adoptions' by other families sound much more reasonable and natural.

Although I have previously expressed idealistic opinions about the early life Yoshiko experienced with the Yamaguchi family, in hindsight there may be other practical reasons why Yoshiko was taken out of Japanese school and allowed to attend the Yong'an school, learn Chinese language as a native, and be 'adopted-out' into Chinese families. I now feel she was 'different' from the very start of her life with the Yamaguchi family (and by different I mean racial as well as facial features). It's very painful for a 'different' child in a typical Japanese school (the old Japanese saying being "a nail which sticks up gets pounded down"). The most logical reason she attended Yong-an school was that she could not fit in with the Japanese school and was probably bullied by classmates (just like happens today).

The same could be said when it came time to attend a high school in Fengtian: no ordinary Mukden school would suffice; instead she was sent to Beijing, not to attend an average school, but to attend the prestigious Yijiao mission-school for 'pillar of society' Chinese girls (this school appears to have been the 'finishing school' for the very top-tier of Chinese aristocracy). With her typical low-key style of writing, Yoshiko does not mention these aspects of the Yijiao school in her memoir.

Although I have previously expressed idealistic opinions about the early life Yoshiko experienced with the Yamaguchi family, in hindsight there may be other practical reasons why Yoshiko was taken out of Japanese school and allowed to attend the Yong'an school, learn Chinese language as a native, and be 'adopted-out' into Chinese families. I now feel she was 'different' from the very start of her life with the Yamaguchi family (and by different I mean racial as well as facial features). It's very painful for a 'different' child in a typical Japanese school (the old Japanese saying being "a nail which sticks up gets pounded down"). The most logical reason she attended Yong-an school was that she could not fit in with the Japanese school and was probably bullied by classmates (just like happens today).

The same could be said when it came time to attend a high school in Fengtian: no ordinary Mukden school would suffice; instead she was sent to Beijing, not to attend an average school, but to attend the prestigious Yijiao mission-school for 'pillar of society' Chinese girls (this school appears to have been the 'finishing school' for the very top-tier of Chinese aristocracy). With her typical low-key style of writing, Yoshiko does not mention these aspects of the Yijiao school in her memoir.

The lack of photos of adult family members has a bearing on the subject of whether the family or Yoshiko indeed "had a French ancestor". Did any of her siblings exhibit similar aspects of Yoshiko's adult beauty, ie, large eyes, western nose, curly hair, etc.? it would appear the answer is no. Is it genetically possible to have French genes and have only one child out of 6 or 7 which exhibits their traits? (I honestly don't know the answer to this question). A Japanese professor is researching the "French connection" to the family, which is suspected as being on the mother's side.

The four 'family sitting' photos which we have contain inconsistencies: one of the pictures shows 7 children instead of the 6 mentioned in her memoir. [this TV show host welcomed Seiko "as the oldest of seven children"] There are age inconsistencies between the pictures which I cannot understand (given we don't know who each child was and when each picture was taken). One of the photos appears to be an early example of what today one might call 'photo-shop'. The first photo below is very rare and did not appear in any of Yoshiko's books (one wonders why - could it be that she stands out so differently from all the other children, and she does not appear to be the oldest child). The large black figure of Yoshiko in 3rd picture below (in foreground) looks much older than a young girl. When I look at these photos, I do so realizing that one of the people shown is not like the others:

-who is the extra 7th child (not mentioned in her memoir) in the photo directly above?

Yoshiko never even names all of the people in the above photos, so we don't know which side of the family grandfather is, or who all the children are by name. One would expect a famous person writing a memoir to say "this was me at eight years old" or "picture taken circa 1933", unless there were reasons not to do so.

x--x--x--x--x

Let's then examine closely some chronological events in her life mentioned in her memoir. One of the most important is this one: her train-trip in 1934 from Mukden to Peking. When her father Fumio buys her a 3rd class 'hard-seat' ticket for the overnight train from Mukden to Peking, he says (in the Prof. Chang translation) "you'll be living as a Chinese person from now on, so get used to it" (or in the Stephenson translation) "from now on, you must start being a Chinese person, and must accustom yourself to the Chinese person's lifestyle". If these translations are accurate, this is a completely revelatory statement (not to mention a cold way to say goodbye to your daughter).

Those partial to conspiracy will believe Fumio said "it's been decided you are to go underground now and pretend to be Chinese". On the other hand, if the Yamaguchi family were actually raising a Chinese infant and teaching her Chinese, father's statement "you'll be living as a Chinese person from now on" makes much more sense, despite the cold sentiment. (Is it believable that a Japanese man raises his own daughter for thirteen years, teaching her Chinese from kindergarten age, and then says 'ok, now you're a Chinese person'! it's almost as if he said "I've done my part, now you go live as the Chinese person you always have been". . .). As to her having to travel 3rd class on an overnight train, any father would've bought his daughter a more comfortable (and safe) seat in a carriage where other Japanese would be seated. In those days the 3rd class section was known to be full of live chickens, ducks, garlic, farmers, and the many smells of the poorer class - certainly not a nice place for a 14yr old travelling alone.

I do believe that Yoshiko put her father's words down with the full intention of revealing something to us, knowing that history would examine them some day. When I first heard the coldness of these words, I began to formulate that Fumio was probably not Yoshiko's biological father.

I do believe Fumio's words "from now on, you must start being a Chinese person" confirm the reality of Yoshiko not being his real daughter, ie, in accordance with her Chinese family wishes, she must now go to Peking in order to finish her education as a member of the Chinese-aristocrat class.

As Yoshiko mentions, it was downright dangerous, even for Japanese military personnel to travel on this train through Chinese territory due to the activities of 'bandits'. Would a caring father put his own daughter alone on this train? Any father who loved his daughter would've merely changed the departure date so they could travel together. This episode of her life does not accord with the accepted version of her life, ie, that she was born a Yamaguchi and loved as a daughter. It makes more sense that she is travelling as a Chinese person, albeit someone who has been raised in a Japanese family. Perhaps there are other events in her life which can add confidence to the picture which starts to emerge.

Those partial to conspiracy will believe Fumio said "it's been decided you are to go underground now and pretend to be Chinese". On the other hand, if the Yamaguchi family were actually raising a Chinese infant and teaching her Chinese, father's statement "you'll be living as a Chinese person from now on" makes much more sense, despite the cold sentiment. (Is it believable that a Japanese man raises his own daughter for thirteen years, teaching her Chinese from kindergarten age, and then says 'ok, now you're a Chinese person'! it's almost as if he said "I've done my part, now you go live as the Chinese person you always have been". . .). As to her having to travel 3rd class on an overnight train, any father would've bought his daughter a more comfortable (and safe) seat in a carriage where other Japanese would be seated. In those days the 3rd class section was known to be full of live chickens, ducks, garlic, farmers, and the many smells of the poorer class - certainly not a nice place for a 14yr old travelling alone.

I do believe that Yoshiko put her father's words down with the full intention of revealing something to us, knowing that history would examine them some day. When I first heard the coldness of these words, I began to formulate that Fumio was probably not Yoshiko's biological father.

I do believe Fumio's words "from now on, you must start being a Chinese person" confirm the reality of Yoshiko not being his real daughter, ie, in accordance with her Chinese family wishes, she must now go to Peking in order to finish her education as a member of the Chinese-aristocrat class.

As Yoshiko mentions, it was downright dangerous, even for Japanese military personnel to travel on this train through Chinese territory due to the activities of 'bandits'. Would a caring father put his own daughter alone on this train? Any father who loved his daughter would've merely changed the departure date so they could travel together. This episode of her life does not accord with the accepted version of her life, ie, that she was born a Yamaguchi and loved as a daughter. It makes more sense that she is travelling as a Chinese person, albeit someone who has been raised in a Japanese family. Perhaps there are other events in her life which can add confidence to the picture which starts to emerge.

The BS Asahi TV show mentioned above contains this revealing fact: her sister Seiko states that all the Yamaguchi children referred to Yoshiko as "jiejie". This word is the Mandarin word for 'older sister'. So the Yamaguchi children were actually calling her 'Chinese older sister'. This word by itself (instead of the equivalent Japanese word 'onesan') is a significant check-mark on the side of her actually being a Chinese person.

In 1937 her father Fumio accompanied Yoshiko to Tianjin to meet the famous woman-warrior Kawashima (who by this time had become something of an embarrassment to the Japanese military). It must have been known by Japanese authorities that Kawashima was leading a fairly debauched existence (addicted to drugs, awake all night and asleep all day, surrounded by a 'palace-guard' of young beautiful girls, hangers-on, drug-addicts, etc), and yet the decision was made to introduce Pan Shuhua (ie, our Yoshiko) to her. Would a loving father approve of this meeting, personally accompany her there, and leave his 17yr old daughter almost unchaperoned for her summer vacation in this degenerate situation?

Furthermore, we have what appears to be a daring photo (considering social norms at the time) of a bare-shouldered Yoshiko, perhaps taken at a swimming facility. In her memoir, she admits to sowing some 'wild oats' during her 1937 summer. Although we don't know the date of the photo, it is yet another example of the mystery, daring, and stunning allure of Yamaguchi.

Let us also recall the famous recruiting meeting which Yoshiko has with ToruYamaga and Minoru Yamanishi at which he says "Man'ei was seeking "A native Manchurian girl who could sing, speak Mandarin, and understand Japanese". [Ed: Apparently, they found one!] It should not be lost on us either to understand that the two gentlemen above would not have had to work so hard to coerce a Japanese girl as much as they had to work to coerce the Manchurian girl.

Just as Yoshiko was adopted by the Li and Pan families, she herself is candid about her own 'adoption' of yet another family where "she most felt at home" during the 1938-1942 period of her career. This was the General Yoshioka family, where Yoshiko says she “felt like a sister” to their own daughters Yukiko and Kazuko (and even includes a photo of them in her memoir: well, what about her 'real' sisters, Kyoko, Etsuko, and Seiko? I haven't found any pictures of them, together or not). And contrary to the paucity of stories about the Yamaguchi family, Yoshiko recounts many happy vignettes of life with the Yoshioka family (even down to such details as favorite foods, how bad a tennis-player General Yoshioka was, his hobby of ink-painting calligraphy, and his favorite impromptu song.) This is but further confirmation of her questionable bonds with the Yamaguchi family.

While making her film "Kimi to boku" in Korea in 1941, Yoshiko specifically mentions being brought to a police station to meet "her parents": a Korean couple named Lee who swore she was their long-lost daughter. The Korean couple cried bitterly and thought their missing baby (Yoshiko) had been kidnapped, taken to Manchuria, and raised by another family. They asserted their baby had a mole on her left wrist: Yoshiko was then examined and found to also have a mole in the same location! Stephenson ("Her Traces are Found Everywhere") personally met with Yoshiko in 1996 and confirms she "never really managed to convince them [the Korean parents] that they were wrong".

Yamaguchi did not have to reveal this story in her memoir: why even include it, if not to inform or tantalize the reader with the possibility that it was true? Everything in her memoir is carefully vetted and worded; by including this item, Yoshiko is not only informing us that this type of thing happened in those days, but also that a Korean couple saw their own racial features in Yoshiko's face (she was their baby!) and nothing convinced them otherwise.

Yamaguchi did not have to reveal this story in her memoir: why even include it, if not to inform or tantalize the reader with the possibility that it was true? Everything in her memoir is carefully vetted and worded; by including this item, Yoshiko is not only informing us that this type of thing happened in those days, but also that a Korean couple saw their own racial features in Yoshiko's face (she was their baby!) and nothing convinced them otherwise.

Prior to recounting the above story, Yoshiko says "Come to think of it, ever since I was young, my facial features had never struck anyone as being authentically Japanese" and immediately following, she laments her facial features "which have characteristics of people everywhere in the world, except for the Japanese". Clearly and in her subtle diplomatic way, Yoshiko is telling the reader she could very well be of other origins than Japanese.

Her famous 'seven rings around' the Nichigeki Theater concert of Feb 1941 contains this Man'ei publicity statement which is quoted in her memoir: "Her name is pronounced Ri Koran in Japanese and "Li Xianglan" in the Manchurian language. Born in the eighth year of the Chinese Republic and the ninth year of Taisho, she has just now reached the adorable age of 21. . . Raised in Beijing as the beloved daughter of the mayor of Fengtian, she speaks fluent Japanese just by virtue of attending a school for Japanese children. So what we have is truly a representative young girl from an Asia on the rise, a woman who speaks the three languages of Japanese, Manchurian, and Chinese with remarkable dexterity". First, this statement confirms her name is Li Xianglan and her age as 21. Second, that she is the daughter of Li Jichun. Third, that she learned Japanese in a school (not at home). By putting this quote into her memoir, I believe Yamaguchi 'was hiding in plain sight'.

Her famous 'seven rings around' the Nichigeki Theater concert of Feb 1941 contains this Man'ei publicity statement which is quoted in her memoir: "Her name is pronounced Ri Koran in Japanese and "Li Xianglan" in the Manchurian language. Born in the eighth year of the Chinese Republic and the ninth year of Taisho, she has just now reached the adorable age of 21. . . Raised in Beijing as the beloved daughter of the mayor of Fengtian, she speaks fluent Japanese just by virtue of attending a school for Japanese children. So what we have is truly a representative young girl from an Asia on the rise, a woman who speaks the three languages of Japanese, Manchurian, and Chinese with remarkable dexterity". First, this statement confirms her name is Li Xianglan and her age as 21. Second, that she is the daughter of Li Jichun. Third, that she learned Japanese in a school (not at home). By putting this quote into her memoir, I believe Yamaguchi 'was hiding in plain sight'.

Many of Yoshiko's films reflect or reprise actual elements of her real life.

The art-film/musical "My Nightingale" (filmed in 1943 & 1944) contains one such tantalizing example of art reflecting life: it is the story of a Japanese baby separated from her family during a violent attack, who is then raised by a Russian opera singer. Her natural father searches for her until she is found by him fifteen years later; by this time she had 'become' a Russian girl named Mariya who sings beautifully. Just think how this film-story might be similar to Yoshiko's own story: a baby is separated from her family, adopted and raised by a Japanese family, eventually becoming a famous singer. I think the writers of "My Nightingale" were channeling parts of Yoshiko's own life story.

Another film containing elements of her real life story is the 1952 "Woman of Shanghai" reviewed in "The Attractive Empire" by Michael Baskett. He writes the film "was a fictionalized film biography of Yamaguchi" and "obvious parallels with Yamaguchi's own life can be found" in it.

note "she spoke Japanese clearly and quickly with a Mandarin accent".

note also "a Japanese raised by Chinese foster parents". These quotes tend to support my theory (below) on the biological origins of Yamaguchi.

No one to my knowledge has ever accused Yoshiko of speaking Mandarin with a Japanese accent; in fact the unanimous opinion is that her spoken Chinese was natural and native, whereas the above quote confirms that her spoken Japanese was not natural because of a Mandarin accent. And according to Baskett, she was the only actress in Japan who had natural Chinese language skill.

note also "a Japanese raised by Chinese foster parents". These quotes tend to support my theory (below) on the biological origins of Yamaguchi.

No one to my knowledge has ever accused Yoshiko of speaking Mandarin with a Japanese accent; in fact the unanimous opinion is that her spoken Chinese was natural and native, whereas the above quote confirms that her spoken Japanese was not natural because of a Mandarin accent. And according to Baskett, she was the only actress in Japan who had natural Chinese language skill.

In my view, the fact that no other Japanese actor was able to learn native Chinese speaking ability is very telling and points to her not being Japanese.

In a similar vein, and moving forward to the 1991 Shiki Theater musical-production "Li Xianglan": this play contains a fictional character named Li Ailian (LAL) who is a Chinese biological daughter of Li Jichun. The two 'sisters' of LXL and LAL are very close; in the final scene of the play when LXL is on trial for her life, it is LAL who presents the judge with the Japanese family register paper, thereby exonerating her 'sister' LXL. The obvious tantalizing question then becomes: were LXL and LAL one and the same person in real life?

In a similar vein, and moving forward to the 1991 Shiki Theater musical-production "Li Xianglan": this play contains a fictional character named Li Ailian (LAL) who is a Chinese biological daughter of Li Jichun. The two 'sisters' of LXL and LAL are very close; in the final scene of the play when LXL is on trial for her life, it is LAL who presents the judge with the Japanese family register paper, thereby exonerating her 'sister' LXL. The obvious tantalizing question then becomes: were LXL and LAL one and the same person in real life?

In 1945: Her detention and trial in Shanghai lasted for about five months. Her 'protector' during this period was not her father as one might have expected, but Kawakita Nagamasa.

[Kawakita also 'gave her away' in her 1951 marriage to Noguchi, a further sign that father and family was completely out of the picture]

Yoshiko mentions in memoir: "apparently, the only question was whether or not I was really Chinese". There are also these earthy words she quotes from a court official: "ordinary Chinese believe that Chinese blood flows in at least half of your body". The Chinese authorities 'turned over every stone' for months while trying to prove Li Xianglan was Chinese, but (so we are told) were unable to do so (however, there were other factors which may have influenced the court).

[Kawakita also 'gave her away' in her 1951 marriage to Noguchi, a further sign that father and family was completely out of the picture]

Yoshiko mentions in memoir: "apparently, the only question was whether or not I was really Chinese". There are also these earthy words she quotes from a court official: "ordinary Chinese believe that Chinese blood flows in at least half of your body". The Chinese authorities 'turned over every stone' for months while trying to prove Li Xianglan was Chinese, but (so we are told) were unable to do so (however, there were other factors which may have influenced the court).

The political situation at the time of her trial was complicated. The war against the Japanese had just ended and both the KMT and the Communists were trying to control as much territory as possible. Historians have pointed out little known details about how both sides were also actually trying to recruit their former enemy (ex-Japanese military) for the coming civil-war. On two occasions, Yoshiko was approached by unknown parties who offered her the good life in Manchuria, "complete with a house, servants, and a chauffeur-driven Cadillac" if she would agree to spy on Communist activity.

The more history I read, the more I believe the decision by the KMT not to execute Li Xianglan was motivated by political considerations rather than proof she was or was not Chinese. The decision to acquit Li Xianglan made the KMT look merciful (while other political aspects, such as not offending the Japanese military were also satisfied).

The more history I read, the more I believe the decision by the KMT not to execute Li Xianglan was motivated by political considerations rather than proof she was or was not Chinese. The decision to acquit Li Xianglan made the KMT look merciful (while other political aspects, such as not offending the Japanese military were also satisfied).

When her Yamaguchi *family register paper (see below) is presented to the court, the official says: "How can you prove the Yamaguchi Yoshiko recorded on this register and you now standing before me are one and the same person? You don't have any scientific proof such as finger-print verification, do you?". Indeed, there was none, and again it is Yoshiko herself who provides us with this very good ammunition to question her origin:

*Yoshiko writes this passage about the typical family register paper (birth-certificate):

"Kawakita in his "My Life History" described the family register as "crude and strange". You could just print some indecipherable characters on a paper using a stencil. Then you have a cheap-looking seal from the head of so-and-so village; there wasn't even an identification number on the thing! There was no way a foreign official could have any faith in such a dubious document and no way to prove that the Yamaguchi Yoshiko on the document is the same person as Li Xianglan."

Would not the above passage tend to imply that it was fairly easy to 'manufacture' the family register paper? Here again, I think Yoshiko in her subtle way was confirming the obvious, if indeed, an 'old and soiled' piece of paper meant the difference between life and death [ie, between herself and Kawashima].

Yoshiko also says that if Kawashima (born into a royal Qing Chinese family) had been added to the Japanese family register, and had been able to produce a piece of paper, her life would've been saved. We can posit then, in Yamaguchi's case, she may have been adopted also, but was able to produce that 'old and soiled' piece of paper which saved her life.

Pertinent to the above Shanghai trial is a March 2019 book: "Another Girlfriend" by Japanese academic Kenko Kawasaki: もう一人の彼女-山口淑子-シャーリー・ヤマグチ-川崎-賢子 . I cite this book because Kenko points out that Yoshiko's last memoir (see above picture) dated 2004, includes the actual court record of Kawashima's trial! Now this is 'passing strange', and it does raise the question of why we have the formal court record of Kawashima but we don't have the court record of Yamaguchi (since they were contemporaneous trials). Kenko answers this question by claiming that Yamaguchi did not have a formal trial, which explains the lack of court records. Perhaps history in the form of memoirs written by Yamaguchi's contemporaries (or even Chinese government records) will be the final arbiter of this issue.

Yoshiko also says that if Kawashima (born into a royal Qing Chinese family) had been added to the Japanese family register, and had been able to produce a piece of paper, her life would've been saved. We can posit then, in Yamaguchi's case, she may have been adopted also, but was able to produce that 'old and soiled' piece of paper which saved her life.

Pertinent to the above Shanghai trial is a March 2019 book: "Another Girlfriend" by Japanese academic Kenko Kawasaki: もう一人の彼女-山口淑子-シャーリー・ヤマグチ-川崎-賢子 . I cite this book because Kenko points out that Yoshiko's last memoir (see above picture) dated 2004, includes the actual court record of Kawashima's trial! Now this is 'passing strange', and it does raise the question of why we have the formal court record of Kawashima but we don't have the court record of Yamaguchi (since they were contemporaneous trials). Kenko answers this question by claiming that Yamaguchi did not have a formal trial, which explains the lack of court records. Perhaps history in the form of memoirs written by Yamaguchi's contemporaries (or even Chinese government records) will be the final arbiter of this issue.

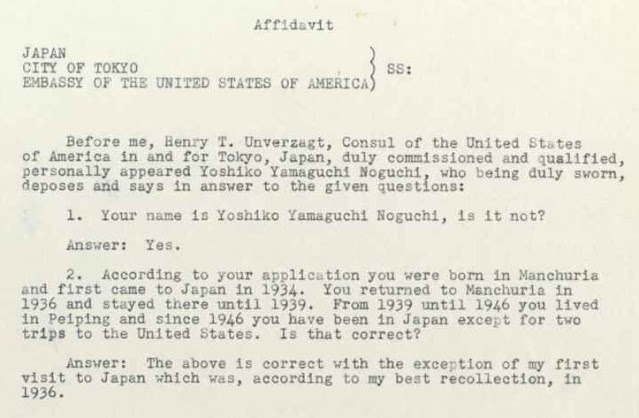

Yamaguchi's memoir states "I was born in the suburbs of present-day Shenyang". But her signed 1950 visa application shows Place of Birth as "Bujun". Granted, this name is close in Chinese pronunciation to "Fushun" and perhaps this is only a minor issue:

Moving forwards in time to the 1950’s, several small UP newspaper clips reported her as saying "I am not Japanese, but a Chinese born in China". United Press was a reputable news organization. Of course, these news-clips are unsubstantiated and may just be hearsay. But many Chinese were convinced she was at least half-Chinese:

Recently, this revealing photo of a young Li Xianglan was acquired by me:

Typical hearsay evidence concerning her origin:

The photo is autographed with her Chinese name, Li Xianglan. I think it obvious that we behold a Chinese girl here: her pose and strong expression and her clothing are all saying "I am Chinese".

Also in the 1950's: Yoshiko's memoirs candidly reveal the underhanded way that father Fumio used her chop/seal to borrow money using her Asagaya house as security, and how she was then forced to legally disown him in order to save the house from being foreclosed. She states "my name and my siblings names were then removed from the Yamaguchi family register".

After he passed away, Yoshiko wrote: "That was the same man who had listened with such undivided attentiveness to my Mandarin pronunciation, the same person who had praised me for having completed a long trip from Fengtian to Beijing, and who had kept the newspaper clippings about my execution in Shanghai with such sympathetic care . . . " if the translation is correct, this is what is called in the west "damning someone by using faint praise".

Her 1987 memoir discusses this question. Chapter 5, titled The Birth of Li Xianglan, quotes Fumio Niwa as saying : "People say this girl is Japanese, but it's not true. She is really Chinese". Yoshiko then says: "For some reason, those words sank deeply within me and remain so until this day." Perhaps Yoshiko is telling us: those words should sink deeply into you, the reader, also.

In this same chapter, Yoshiko makes clear the fact that all of her co-workers at Man'ei assumed she was half Chinese and half Japanese, although her good friends treated her as though she was a fellow Chinese (to the extent they would cease a conversation if a Japanese were to enter into it). This is very telling evidence indeed, ie, of her acceptance as a Chinese person by other Chinese people.

Second is "I was a Chinese made by Japanese hands, it pains me whenever I think about it". The simple and mysterious wording she uses here has always intrigued me because of what they imply. She loved 'becoming' or 'returning to being Chinese' at the time. Later in her life she often frankly stated "China is my home" [see the Buruma 1989 interview for instance]. However, her quote makes more sense to me if she is really saying here I was, born a Chinese person, and the Japanese tried to make me into a Japanese person, and subsequently I found out my nature was basically Chinese, and it caused me a lifetime of pain.

Third would be her expression of "great guilt" and "wish to atone" to the Chinese people. This guilt, the urge to atone, and the pain, would be greatly increased if in fact she was born some percentage of Chinese, for obvious reasons. Stephenson in "Her Traces Are Found Everywhere" confirms that in 1944 Yoshiko said ". . . I have always felt that I have let us Chinese people down". Although I would not consider this a 'smoking gun' of proof, it does add to the totality of my case. And of course, I have always maintained throughout my research that Yoshiko is above blame for anything and everything she did at a young age. [allow me to also add here that academics like the one above usually accuse Yoshiko of wearing a qipao dress (cheongsam) as a "costume": There is no doubt in my mind that Yoshiko's lifelong wearing of the qipao was serious and actually a signal to the world of her Chinese roots. There was no better reason for Yoshiko to be wearing a Chinese collar in the 1950s when this gorgeous picture was taken.]

Fourth is her statement at the c.1937 student's anti-Japanese demonstration: "I will stand on the City wall" [Ed: and take a bullet from either side]. Given the heated emotions of the situation, where everyone was shouting rabid anti-Japanese slogans, Yoshiko's declaration was bravely even-handed to both sides, and could have easily attracted scorn as not being anti-Japanese enough.

In 1991, she said "Even now, it hurts me" while remembering the reporter who asked her in 1943: "you are Chinese - right? So how could you appear in movies that offended China? Don't you have any pride as a Chinese?". And in her 2004 interview recounting the Shimonoseki ferry incident she states "I took those words as if I were Chinese . . . I grew to hate Japanese people. What a nasty group of people . . . with their blatant feelings of superiority and prejudice . .". Obviously, in all these quotes she is speaking and feeling as a Chinese person.

Finally, in Chapter 2 My Fengtian Years, Yoshiko states that Li Jichun "was also kind enough to take a liking to me as if I were his own daughter". Here is another interesting memoir statement: "I was a spiritual mixed-race child between Japan and China". The sentence could well be interpreted as saying 'I am spiritual, and half-Japanese and half-Chinese'.

After he passed away, Yoshiko wrote: "That was the same man who had listened with such undivided attentiveness to my Mandarin pronunciation, the same person who had praised me for having completed a long trip from Fengtian to Beijing, and who had kept the newspaper clippings about my execution in Shanghai with such sympathetic care . . . " if the translation is correct, this is what is called in the west "damning someone by using faint praise".

x--x--x--x--x

Finally, let us consider Yoshiko's own quotes about her life; for me the main one is her 2012 "Am I Japanese or am I Chinese?". While most researchers consider this a rhetorical question, she may have indirectly meant it quite literally (ie, who am I descended from?). Her 1987 memoir discusses this question. Chapter 5, titled The Birth of Li Xianglan, quotes Fumio Niwa as saying : "People say this girl is Japanese, but it's not true. She is really Chinese". Yoshiko then says: "For some reason, those words sank deeply within me and remain so until this day." Perhaps Yoshiko is telling us: those words should sink deeply into you, the reader, also.

In this same chapter, Yoshiko makes clear the fact that all of her co-workers at Man'ei assumed she was half Chinese and half Japanese, although her good friends treated her as though she was a fellow Chinese (to the extent they would cease a conversation if a Japanese were to enter into it). This is very telling evidence indeed, ie, of her acceptance as a Chinese person by other Chinese people.

Second is "I was a Chinese made by Japanese hands, it pains me whenever I think about it". The simple and mysterious wording she uses here has always intrigued me because of what they imply. She loved 'becoming' or 'returning to being Chinese' at the time. Later in her life she often frankly stated "China is my home" [see the Buruma 1989 interview for instance]. However, her quote makes more sense to me if she is really saying here I was, born a Chinese person, and the Japanese tried to make me into a Japanese person, and subsequently I found out my nature was basically Chinese, and it caused me a lifetime of pain.

Third would be her expression of "great guilt" and "wish to atone" to the Chinese people. This guilt, the urge to atone, and the pain, would be greatly increased if in fact she was born some percentage of Chinese, for obvious reasons. Stephenson in "Her Traces Are Found Everywhere" confirms that in 1944 Yoshiko said ". . . I have always felt that I have let us Chinese people down". Although I would not consider this a 'smoking gun' of proof, it does add to the totality of my case. And of course, I have always maintained throughout my research that Yoshiko is above blame for anything and everything she did at a young age. [allow me to also add here that academics like the one above usually accuse Yoshiko of wearing a qipao dress (cheongsam) as a "costume": There is no doubt in my mind that Yoshiko's lifelong wearing of the qipao was serious and actually a signal to the world of her Chinese roots. There was no better reason for Yoshiko to be wearing a Chinese collar in the 1950s when this gorgeous picture was taken.]

Fourth is her statement at the c.1937 student's anti-Japanese demonstration: "I will stand on the City wall" [Ed: and take a bullet from either side]. Given the heated emotions of the situation, where everyone was shouting rabid anti-Japanese slogans, Yoshiko's declaration was bravely even-handed to both sides, and could have easily attracted scorn as not being anti-Japanese enough.

In 1991, she said "Even now, it hurts me" while remembering the reporter who asked her in 1943: "you are Chinese - right? So how could you appear in movies that offended China? Don't you have any pride as a Chinese?". And in her 2004 interview recounting the Shimonoseki ferry incident she states "I took those words as if I were Chinese . . . I grew to hate Japanese people. What a nasty group of people . . . with their blatant feelings of superiority and prejudice . .". Obviously, in all these quotes she is speaking and feeling as a Chinese person.

Finally, in Chapter 2 My Fengtian Years, Yoshiko states that Li Jichun "was also kind enough to take a liking to me as if I were his own daughter". Here is another interesting memoir statement: "I was a spiritual mixed-race child between Japan and China". The sentence could well be interpreted as saying 'I am spiritual, and half-Japanese and half-Chinese'.

x--x--x--x--x

Based on the preceding points, one could logically ask:

1. Was Yoshiko a biological daughter of Fumio and Aiko Yamaguchi?

It appears she was not, given all of the information I have gathered about her life. She seems to have been different from her siblings and parents, and subsequently (as she said in her memoirs) they all went their own way in life.

[in her memoir, Yoshiko makes a point of informing the reader that her parents, "being from the Meiji period" did not even inform her if romance brought them together or whether they had a traditional arranged marriage. There are no marriage pictures extant that I (John M) have been able to find. Since they were secretive about this matter, it is reasonable to think they could have kept other secrets.]

It appears she was not, given all of the information I have gathered about her life. She seems to have been different from her siblings and parents, and subsequently (as she said in her memoirs) they all went their own way in life.

[in her memoir, Yoshiko makes a point of informing the reader that her parents, "being from the Meiji period" did not even inform her if romance brought them together or whether they had a traditional arranged marriage. There are no marriage pictures extant that I (John M) have been able to find. Since they were secretive about this matter, it is reasonable to think they could have kept other secrets.]

Recently, while researching the Isamu Noguchi Archive, I came across this document (from a June 1953 Affidavit conducted by the American Consulate in Tokyo):

Of interest is the "My family and I have no connection with each other". I interpret this to be further confirmation of her not being a biologic part of the Yamaguchi family.

2. Could she have been adopted at birth or at a very early age?

Yes, adoption was not only possible but prevalent in those days; her memoir clearly states she was adopted twice, so a possible third adoption is not out of the question (objectively, it would appear she was 'passed' from one family to the next). One must also bear in mind the lack of 'legal papers' in a chaotic China of that time. The earliest picture of Yoshiko and her parents (far right) does not appear to show a new-born baby.

Yes, adoption was not only possible but prevalent in those days; her memoir clearly states she was adopted twice, so a possible third adoption is not out of the question (objectively, it would appear she was 'passed' from one family to the next). One must also bear in mind the lack of 'legal papers' in a chaotic China of that time. The earliest picture of Yoshiko and her parents (far right) does not appear to show a new-born baby.

Her memoir states on Page 1: "my whole family moved to Fushun soon after I was born": such a move could well be interpreted as a convenient way to conceal an adoption.

As to her origin, perhaps she was a 'love-child' from a close or distant Yamaguchi relative, or possibly from the large and extended Li or Pan Chinese aristocrat families, or a 'foundling' from one of the war-zones in northern China. I could well believe that her biological father was either Mr. Li or Pan (both having at least two wives and many concubines also). Yoshiko specifically mentions that Mr. Pan's first wife did not produce a son, necessitating him taking a second wife, "who gave birth to 3 boys and 7 girls".

Obviously, Yoshiko must have been aware and wondered about these matters; if she suspected or knew anything definite it seems to have been taken to the grave by her. And it does not diminish her life one iota in my eyes if what I propose has some truth to it.

Of interest is the "My family and I have no connection with each other". I interpret this to be further confirmation of her not being a biologic part of the Yamaguchi family.

2. Could she have been adopted at birth or at a very early age?

Yes, adoption was not only possible but prevalent in those days; her memoir clearly states she was adopted twice, so a possible third adoption is not out of the question (objectively, it would appear she was 'passed' from one family to the next). One must also bear in mind the lack of 'legal papers' in a chaotic China of that time. The earliest picture of Yoshiko and her parents (far right) does not appear to show a new-born baby.

Yes, adoption was not only possible but prevalent in those days; her memoir clearly states she was adopted twice, so a possible third adoption is not out of the question (objectively, it would appear she was 'passed' from one family to the next). One must also bear in mind the lack of 'legal papers' in a chaotic China of that time. The earliest picture of Yoshiko and her parents (far right) does not appear to show a new-born baby. Her memoir states on Page 1: "my whole family moved to Fushun soon after I was born": such a move could well be interpreted as a convenient way to conceal an adoption.

As to her origin, perhaps she was a 'love-child' from a close or distant Yamaguchi relative, or possibly from the large and extended Li or Pan Chinese aristocrat families, or a 'foundling' from one of the war-zones in northern China. I could well believe that her biological father was either Mr. Li or Pan (both having at least two wives and many concubines also). Yoshiko specifically mentions that Mr. Pan's first wife did not produce a son, necessitating him taking a second wife, "who gave birth to 3 boys and 7 girls".

Obviously, Yoshiko must have been aware and wondered about these matters; if she suspected or knew anything definite it seems to have been taken to the grave by her. And it does not diminish her life one iota in my eyes if what I propose has some truth to it.

3. Yoshiko's facility with the Chinese language: is it possible her birth mother was Chinese, and she heard the tones of Chinese language and culture while still inside the womb and/or for a short period after she was born? Her father Fumio recognized her facility with the Chinese language quite early on and hence tutored her, but none of the other Yamaguchi children seems to have had a similar talent or was similarly tutored. [and indeed, she confirms in these 2007/8 Asahi Shimbun interviews that she was the only child educated in the Chinese language].

4. Could there be some significance to the sad fact that Yoshiko's demise was not honored (or even noted) by any Japanese government source that I have been able to find. However, the Chinese government Ministry of Foreign Affairs Hong Lei did honor Li Xianglan's death in an official statement. Is it not significant that this statement refers to her as "Ms. Li Xianglan" instead of her Japanese name Yamaguchi, which the 1945 Chinese court accepted as her real name?

4. Could there be some significance to the sad fact that Yoshiko's demise was not honored (or even noted) by any Japanese government source that I have been able to find. However, the Chinese government Ministry of Foreign Affairs Hong Lei did honor Li Xianglan's death in an official statement. Is it not significant that this statement refers to her as "Ms. Li Xianglan" instead of her Japanese name Yamaguchi, which the 1945 Chinese court accepted as her real name?

5. Does right-wing hatred of Yamaguchi explain the official Japanese government neglect, or is there a further racial component to the question?

If Yoshiko were truly Japanese, and accepted as Japanese, one would have expected the Japanese government (which she faithfully served for eighteen years in the Diet, not to mention her early years in China) to at least acknowledge her passing as marking the end of an historic era. However, if you look closely at her Marriage Certificate of 1951, it says she is not a Citizen of Japan, but is a Subject of Japan. This is a revealing piece of information, wouldn't you agree?

4. Could there be some significance to the sad fact that Yoshiko's demise was not honored (or even noted) by any Japanese government source that I have been able to find. However, the Chinese government Ministry of Foreign Affairs Hong Lei did honor Li Xianglan's death in an official statement. Is it not significant that this statement refers to her as "Ms. Li Xianglan" instead of her Japanese name Yamaguchi, which the 1945 Chinese court accepted as her real name?

4. Could there be some significance to the sad fact that Yoshiko's demise was not honored (or even noted) by any Japanese government source that I have been able to find. However, the Chinese government Ministry of Foreign Affairs Hong Lei did honor Li Xianglan's death in an official statement. Is it not significant that this statement refers to her as "Ms. Li Xianglan" instead of her Japanese name Yamaguchi, which the 1945 Chinese court accepted as her real name?

5. Does right-wing hatred of Yamaguchi explain the official Japanese government neglect, or is there a further racial component to the question?

If Yoshiko were truly Japanese, and accepted as Japanese, one would have expected the Japanese government (which she faithfully served for eighteen years in the Diet, not to mention her early years in China) to at least acknowledge her passing as marking the end of an historic era. However, if you look closely at her Marriage Certificate of 1951, it says she is not a Citizen of Japan, but is a Subject of Japan. This is a revealing piece of information, wouldn't you agree?

x--x--x--x--x

John M. theory about Li Xianglan/Yoshiko Yamaguchi origin.

1. Her birth-name was Li Xianglan. She was not a 100% biological Yamaguchi (if indeed she had any percentage at all). Her exact parentage is unknown at this point in time, but perhaps her quote "China is my motherland, Japan my fatherland" is a big clue.

1. Her birth-name was Li Xianglan. She was not a 100% biological Yamaguchi (if indeed she had any percentage at all). Her exact parentage is unknown at this point in time, but perhaps her quote "China is my motherland, Japan my fatherland" is a big clue. At her birth, someone looked down at her perfectly formed baby face and said "what a sweet flower you are!" and presciently named her Xiang Lan (or fragrant orchid). She may have been a foundling from a war-zone, or because of her surname Li, more likely a daughter of Li Jichun or a relative in his extensive household and an unknown mother, possibly Japanese (possibly from the Ishibashi clan - ie, mother's side - both Aiko (a beauty in her own right) and Yoshiko were quite short in stature whereas Fumio was tall).

Li Jichun was a major participant in the warlord military history of north and east China during the 1912 - 1945 period and especially during the founding of Manchukuo.

1a. The controversy over the actual number of children in the Yamaguchi family (6 as mentioned in Yoshiko's memoirs vs 7 mentioned above and by this retrospective 2016 TV show host) obviously could point to Yoshiko herself as being the 7th child.

2. Shortly after her birth, Li Xianglan was given to (and/or adopted by) the Yamaguchi family, who then moved to Fushun (where it can be posited the family presented the baby as their own). Her new name Yoshiko Yamaguchi was then entered into the family register (the Japanese equivalent of a birth-certificate) either immediately or at some time in the then-future. A possible scenario which could explain this: if the first Yamaguchi baby was stillborn, an adopted baby would help assuage the family's pain, and could have assumed it's identity (there being many stories of assumed identity in the prevailing culture). Another scenario might involve Fumio, say marrying someone who already had a child, since this is also a common human situation.

She was certainly raised in her formative years (to about age fourteen) by the Yamaguchi family (but as she points out in her memoir, not forced to study the traditional school-subjects which all Japanese girls study - yet another indicator that she was 'different' from birth). In effect she was not raised as a typical Japanese girl, and this may be due to her strong Chinese genes resisting the efforts of her parents to treat her as a Japanese child (if in fact they did).

Even so, there were certainly aspects of Japanese culture which inevitably worked there way into Li Xianglan's character (hard work, obeyance to authority, courtesy and diplomacy, courage, stoic attitude, etc). She is perhaps a fascinating example of the 'nurture vs. nature' question personified. And of course the most important aspect impacting her growth was to internalize and appreciate both cultures (the idealist adults who made these arrangements were thinking of the future of Manchukuo and how it would need exactly the type of person that Yoshiko was and ultimately became).

3. Fumio Yamaguchi treated Yoshiko from kindergarten age as if she were Chinese, going so far as teaching her Mandarin in adult evening classes, allowing her to transfer in second grade to the local Manchurian Yong-an school from a Japanese school, and letting her completely depart the family at age fourteen, facilitating her 'return' to the Chinese society from whence she had come.

My assessment is that Fumio would not have taken these steps with a biological daughter, and he did not do anything similar with his other children. The fact that Fumio did not go to Shanghai in 1945 to protect his daughter, and apparently allowed Kawakita to be her 'protector', speaks to his not being her real father (Yoshiko does not mention whether he tried to and what efforts he may have made to get to Shanghai).

Yoshiko's mother Ai would not have been happy having to give up her eldest daughter who was in effect her 'right-hand-man' in taking care of 5 other siblings - another consideration which lends weight to the theory (I don't believe she would have parted with a biological daughter).

One could conclude from these initial facts that Yoshiko was part Japanese and part Chinese (especially so if in fact she came from the Li family, who would more likely want her raised by a Chinese family if she were 100% Chinese).

4. After the Chinese rebel attack of September 1932 on the Fushun Coal Mine, the Yamaguchi family was forced to re-locate their household to the Li Jichun family compound in Mukden. Li Xianglan in effect returned to her origin point and in a memorable 'adoption' ceremony was welcomed back into the Li family. It was then decided she would leave Mukden and join another Chinese family while attending a prestigious Chinese mission school in Peking. [both the Yamaguchi and Li families (not to mention also the Pan family) made this decision - possibly a psychologically devastating situation for a fourteen your old who thinks she is purely Japanese]. Fumio then put her on the train to travel alone through dangerous 'bandit' country. This move to Peking caused her severe depression in her teen years (as she no doubt wondered why she had to be torn away from her childhood family in Fengtian in order to study in Peking and why if she were Japanese she was 'given-away' to Chinese families). Although Li never mentions the subject of abuse in her memoir, any such abuse she might have experienced at the hands of the Li or Pan family would only have added to her sense of estrangement from the Yamaguchi family.

5. The Pan family. For some as yet unknown reason (possibly as a reaction by Li Xianglan at being cruelly torn from her life in Manchuria) she agreed to be adopted by the Pan family and renamed Pan Shuhua. It could point to her frame of mind as being "ok - if I'm no longer a Yamaguchi, I'm free to join the Pan family". Perhaps someone forbid her using her real name Li Xianglan in Peking, forcing her to take the new name. We can understand why the prominent (and collaborationist) Li family might want to conceal her identity for her own safety in Peking, but the Pan family was essentially no different. The fact she took another Chinese name rather than a Japanese name is in keeping with my overall theory.

Perhaps Chinese researchers can find the records of the Yijiao Girl's Mission School which Li attended or other sources, such as friends of hers who may have written down memories of her. [Other sources of historical information on Li Xianglan may be contained in the Chinese memoirs of famous song-birds such as Bai Guang or Yao Lee and other luminaries who knew her].

5a. As a child raised by a Japanese family, Yoshiko would never have questioned such a thing as whether Fumio and Ai were her natural father and mother (and her siblings also would not have questioned whether she was a real sister). So as a young teenager in Shenyang (Mukden), she most likely still fully believed she was Japanese. I conjecture perhaps her knowledge she was other than a natural Yamaguchi daughter occurred around the age of fourteen when it was decided she must go to Beijing.

2. Shortly after her birth, Li Xianglan was given to (and/or adopted by) the Yamaguchi family, who then moved to Fushun (where it can be posited the family presented the baby as their own). Her new name Yoshiko Yamaguchi was then entered into the family register (the Japanese equivalent of a birth-certificate) either immediately or at some time in the then-future. A possible scenario which could explain this: if the first Yamaguchi baby was stillborn, an adopted baby would help assuage the family's pain, and could have assumed it's identity (there being many stories of assumed identity in the prevailing culture). Another scenario might involve Fumio, say marrying someone who already had a child, since this is also a common human situation.

She was certainly raised in her formative years (to about age fourteen) by the Yamaguchi family (but as she points out in her memoir, not forced to study the traditional school-subjects which all Japanese girls study - yet another indicator that she was 'different' from birth). In effect she was not raised as a typical Japanese girl, and this may be due to her strong Chinese genes resisting the efforts of her parents to treat her as a Japanese child (if in fact they did).