Note: You can read many U.S. newspaper clippings concerning these years at:

https://yoshikoyamaguchi.blogspot.com/p/articles.html

Marriage: Dec 1951 - 1956, to Isamu Noguchi, a noted Japanese-American sculptor

the happiness expressed in her face in these photos was unprecedented:

above and below photos taken at wedding reception, 1951. According to the recent book "Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi", by Hayden Herrera, Isamu designed Yoshiko's kimono and waist sash - it does not have the layered lines of a traditional kimono because it's been made using less material and with modern hooked-dress technique:

the book can be ordered here:

http://www.amazon.com/Listening-Stone-Life-Isamu-Noguchi/dp/0374281165

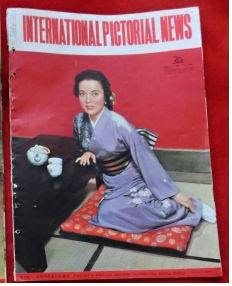

Yoshiko in traditional kimono:

in this video the author Herrera discusses her above book about Noguchi

taken on day of their marriage, Dec 15, 1951:

at Eames House: Man, Woman, Architecture:

other striking photos taken at the Eames House:

Chaplin does a passable imitation of a Japanese Noh dance:

[at least we know who performed that tea ceremony in 1951, even if the New York Times does not seem to know . . . ]

Lastly, this perceptive article on Noguchi by Michael Upchurch from the The Seattle Times:

on a trip to Egypt: (this must've been fun - I can imagine Yoshiko squealing as the camel stood up)

here the author Hayden Herrera describes the above picture:

the below sentence begins, "Rosanjin forbade her to . . . "

Noguchi biographer Herrera puts it very well:

Yoshiko did suffer two miscarriages. She writes in her memoir that this also probably had a negative effect on her marriage with Isamu - the fact "they had no children" and she never mentions the subject of children again in her memoirs.

one of the most famous shots of Yoshiko ever taken, in 1952 Hong Kong, by the great 'social realism' photographer Ken Domon, who had a gift of snapping a picture at just the right time:

https://yoshikoyamaguchi.blogspot.com/p/articles.html

Marriage: Dec 1951 - 1956, to Isamu Noguchi, a noted Japanese-American sculptor

the happiness expressed in her face in these photos was unprecedented:

above and below photos taken at wedding reception, 1951. According to the recent book "Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi", by Hayden Herrera, Isamu designed Yoshiko's kimono and waist sash - it does not have the layered lines of a traditional kimono because it's been made using less material and with modern hooked-dress technique:

the book can be ordered here:

http://www.amazon.com/Listening-Stone-Life-Isamu-Noguchi/dp/0374281165

Yoshiko in traditional kimono:

in this video the author Herrera discusses her above book about Noguchi

taken on day of their marriage, Dec 15, 1951:

menu (complete with haiku and graffiti) from their wedding day:

. . . was Yoshiko not a citizen of Japan?? see the above document.

While in Hollywood during the shooting of Japanese War Bride, they were invited to the Charles Eames House in Santa Monica. Charlie Chaplin was the honored guest and Yoshiko was asked to prepare his favorite dish (sukiyaki) and to conduct a Japanese tea ceremony. The below pictures were taken at this party:

Yoshiko conducts a tea ceremony at the Eames House: a rare photo:

the house, in Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, CA is now a National Landmark:

at Eames House: Man, Woman, Architecture:

other striking photos taken at the Eames House:

Yoshiko writes that she thought the world of Charles Chaplin, and learned a lot from him.

In 2012, the NYTimes published an article about the Eames House quoted here:

"Other designers have taken pains to safeguard their cultural legacies. The Japanese-American designer Isamu Noguchi ensured that his archive would be protected by setting up a private foundation to manage both it and the Noguchi Museum, which he built in the Long Island City neighborhood of Queens in New York, and opened in 1985, three years before his death.

Similarly, the Eames family was determined to conserve the house that the American designers Charles and his wife Ray Eames had built for themselves in the late 1940s on a meadow in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles. The family established a nonprofit foundation to run it.

“Our mom, Lucia Eames, Charles’s daughter, realized the only way to save the house was to create the foundation,” explained her son Eames Demetrios, who is the foundation’s chairman. “The house is on three acres overlooking the Pacific Ocean, and if we had sold it, it would have been turned into condominiums.”

The running costs of the Eames House are now funded partly by the Eames design company and partly by Vitra and Hermann Miller, the manufacturers of their furniture. The foundation also organizes fund-raising events to cover additional costs, such as a $1.5 million restoration program. On March 10, the foundation will stage a recreation of a Japanese tea ceremony held in the Eames House in 1951 with Noguchi and Charlie Chaplin among the guests. Tickets will cost $5,000 for each guest."

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/23/arts/design/preserving-fragile-memories-of-genius.html?_r=0[at least we know who performed that tea ceremony in 1951, even if the New York Times does not seem to know . . . ]

Lastly, this perceptive article on Noguchi by Michael Upchurch from the The Seattle Times:

‘Listening to Stone’: Definitive biography of ‘Black Sun’ sculptor Isamu Noguchi

Hayden

Herrera’s new biography of Isamu Noguchi, “Listening to Stone,”

charts the life of the flawed and visionary sculptor who created the

“Black Sun” sculpture in Seattle’s Volunteer Park

Originally

published Sunday, April 26, 2015

Isamu

Noguchi’s sculpture “Black Sun” serves as a sort of anchoring

lens through which to savor the glorious setting of Seattle’s

Volunteer Park.

Through

the void at its center, you can take in views of the Space Needle,

Puget Sound and the Olympic Peninsula. The power of the piece stems

from its imposing heft and its meditative quality.

One

other thing: People like to play with it. Every day you’ll find

adults and children alike posing for pictures in front of it, racing

around it, peeking through the gap in its center. It’s fitting,

then, that “Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi”

includes a photograph of the artist himself peering mischievously

through the hole in his mighty cosmic doughnut.

Even

Seattleites long familiar with “Black Sun” may know little about

Noguchi. Hayden Herrera’s welcome and comprehensive biography of

him provides a definitive portrait of a figure who, by the time he

died in 1988, was seen by many critics as the greatest American

sculptor of the 20th century.

“Listening

to Stone” is a complex account of a flawed and restless visionary

torn by inner conflicts of identity. Noguchi was an idealistic

aesthete who was irascible and manipulative in his dealings with his

collaborators. A self-declared outsider, he had connections with a

string of 20th-century arts celebrities, including Constantin

Brancusi, Frida Kahlo, Martha Graham, Arshile Gorky, Buckminster

Fuller and famed Japanese actress Shirley Yamaguchi, to whom he was

briefly married.

Noguchi’s

insecurities and pan-global artistic sensibility both can be traced

to his childhood. He was born in Los Angeles in 1904 to a

freethinking American woman and a self-absorbed Japanese father (poet

Yone Noguchi, who hung out with W.B. Yeats and George Bernard Shaw).

Their relationship didn’t last even a year, and when mother and

child followed Yone to Japan, he barely acknowledged them.

Still,

the future sculptor’s early exposure to Japanese culture —

especially Zen gardens and Japanese houses — influenced him

powerfully, especially in his creation of calm-inducing public

spaces.

Herrera

follows Noguchi’s progression from Japan to boarding school in

Indiana, apprenticeship in New York to sculptor Gutzon Borglum

(future creator of Mount Rushmore) and service as Brancusi’s studio

assistant in 1920s Paris. By the 1930s, he’d won acclaim as a

portraitist in stone and as a designer of stage sets and costumes for

choreographer Graham.

Wanderings

to China led to ink-brush painting experiments with Peking artist Qi

Baishi (subject of a recent exhibit at the Frye Art Museum). A stay

in Mexico City led to an affair with Kahlo — and gun-waving threats

from her philandering husband Diego Rivera.

The

strangest chapter in Noguchi’s life came during World War II when

he voluntarily joined ethnic Japanese evacuees at an internment camp

in Arizona with the idea of boosting their morale. His idealism

didn’t last long, once he realized he was being treated as just

another internee.

Postwar,

Noguchi was increasingly involved in designing public spaces — the

UNESCO garden in Paris, Yale University’s Beinecke Library garden,

the Billy Rose Sculpture Garden in Jerusalem — while still creating

personal work. His aim, he said, was to form “order out of chaos, a

myth out of the world, a sense of belonging out of our loneliness.”

Herrera

lucidly details the imagination, frustrations and temperamental

outbursts that went into Noguichi’s projects, while placing the

itinerant artist’s mournful mantra — “I am always nowhere” —

at the heart of her book.

by

Michael Upchurch

x--x--x--x--x

1953: While on a trip with Isamu to world-famous places:

Isamu (the photographer) compares Yoshiko with Athenian Greek goddesses:

what a stunning photo this is !on a trip to Egypt: (this must've been fun - I can imagine Yoshiko squealing as the camel stood up)

She mentions in her memoir that those traditional Japanese 'clogs' were very hard on her feet.

This love-note from Yoshiko was found in the Noguchi Archive:

below: yes, that's Isamu and Yoshiko walking to their beautiful tea-house in Ofuna, Japan: it was rented from the noted artist Rosanjin Kitaoji. The picture is idyllic, but from the tone of Yamaguchi's memoir, we can guess her feet were hurting and that the marriage was gradually slipping away as both artists realized the differences between themselves. Both had strong personalities. Yoshiko refers to the cake (shone in a previous picture) which says "East is East" and she draws the parallel "West is West" in comparing herself (eastern) to the Americanized (western) Isamu.

the below sentence begins, "Rosanjin forbade her to . . . "

Noguchi biographer Herrera puts it very well:

Hiroi was married to one of the Yamaguchi sisters. The sandal episode speaks for itself regarding the deterioration of the love match. The quote "It was hard for me to become a work of Isamu" is quite telling.

The below recounting of "When we went to a friend's house and I gave a gift to the host and I said this is from us he would deny it" needs to be more fully explained. A perfectionist such as Noguchi would understandably object to someone giving a gift which he himself had not seen (perhaps it did not have enough 'art' or was a simple 'off-the-shelf' box of chocolates, etc). But from an eastern point of view, the gesture and courtesy of purchasing and wrapping and bringing the gift were more important than the very gift itself. There is an old Chinese apocryphal proverb that says: "curse your wife at dinner; sleep alone" which I think apropos to this general situation. Noguchi in his western truthfulness about the gift was inadvertently stepping on Yoshiko's eastern attempts to be a well-mannered guest.

I don't believe Yamaguchi has ever said "she would never be able to bear a child", because that would have meant predicting a barren future, and it was not characteristic of Yoshiko to make such a statement.Yoshiko did suffer two miscarriages. She writes in her memoir that this also probably had a negative effect on her marriage with Isamu - the fact "they had no children" and she never mentions the subject of children again in her memoirs.

x-x-x-x-x

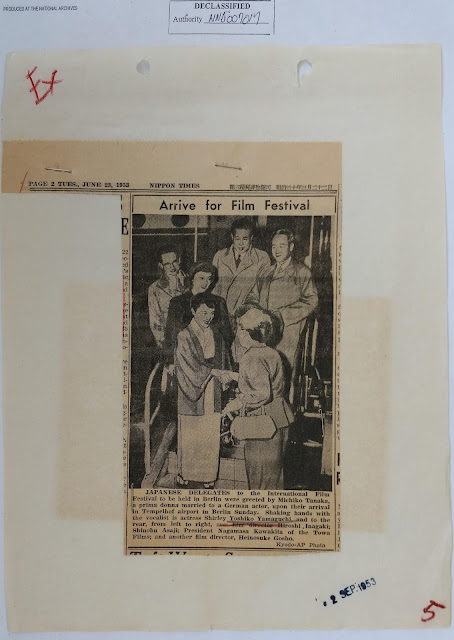

Yamaguchi was denied visa entry into the United States from Dec 1952 to May 1954 because of suspected 'communist agent espionage'. This visa action had a very deleterious effect on both Yoshiko's and Isamu's career and also their marriage.

He missed out on several design commissions and she was prevented from starring in movie projects and several Broadway plays which would have featured her beautiful singing. The Noguchi Archive contains dozens of letters from Noguchi to his attorneys and friends and between Isamu and Yoshiko. The following letter is a dejected Yoshiko mentioning an early divorce if her visa is not approved soon:

See the Intelligence files page for more details (a 10 page report) on the basic charges suspected against her and Noguchi by an over-zealous 1950's intelligence community; they did call this the great "Red Scare".

Here are all the newspaper articles from the intelligence file:

Yoshiko went elsewhere while the visa situation worked itself out. At an EMI music party in Hong Kong:

a flock of beautiful famous songbirds:

there were many such parties:

in another 1953 film named Hoyo (Last Embrace) with Toshiro Mifune:

this well-written 5 page Civil Intelligence report by a Mr. Kawamoto tells the whole Ri Koran story better than I can:

while in Paris, 1953 (Yoshiko and Isamu visited Chaplin in Switzerland also):

quite a revealing article:

Hong-Kong movies for Shaw Brothers:

Li Xianglan as the quintessential Chinese Princess:

This link is to an 85 page scrapbook of pictures provided by Hong Kong reader KYL.

Li Xianglan (on the left below) in Chinese Opera:

House of Bamboo, 1955:

Link to opening scene of movie with Mt. Fuji in background.

read an extensive review of House of Bamboo at this site.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gcN4BxiQsS8

(unfortunately there is no sound in these video clips)

The director, Sam Fuller, wrote his memoir The Third Face in 2007 and explained some of the story behind the making of House of Bamboo:

here is Fuller with Yoshiko "setting up a tricky scene at the waterfront market in Tokyo":

the above scene contains an outlandish dance sequence:

below is the unflattering picture that the New York Times featured in Yamaguchi's obituary

an example of propaganda the Times uses against people whose politics don't follow The Party Line: one of the biggest stars in Asian history is shown as a massage lady for a lucky white guy. The image provides a great low-road opportunity for the Times, and all because she went to Lebanon and refugee camps and supported the Palestinians and interviewed verboten people like Leila Khaled and Yasir Arafat: shame on you NYTimes! (and shame on you too Hollywood, for your lack of imagination and taste outside of the prurient !). For goodness-sake, couldn't you have included some of her great music in your film about gangster Americans and their "kimonos" ???Yoshiko writes that she almost didn't take the part in House of Bamboo because of it's inaccurate portrayal of everyday life in Japan. And she received a lot of criticism for accepting the role; especially later on from vitriolic feminist writers who had their own uses for her body of work.

She probably made the movie because she was living with her husband Noguchi in Kamakura at the time, and the many exterior shots in the movie were within daily driving distance.

This, and the fact that as a major production of 20th Century Fox, the movie starred well-known actors Sessue Hayakawa, Robert Ryan, Robert Stack, Cameron Mitchell, and was one of the first U.S. films to show Japanese people as normal ordinary people. So the potential of the film was great, even though the story-line involved tawdry crime (like most lurid film noir of the time did).

The director, Samuel Fuller, using the new technology of CinemaScope captured the city of Tokyo in many spectacular shots, especially the opening scene of Mount Fuji in the distant landscape, and the closing scene high above the Tokyo streets.

Here is Yoshiko crossing the street to the Imperial Hotel (Frank L. Wright designed this hotel structure and it withstood a large earthquake in 1922):

Even the famous Nichigeki Theatre makes it into the background scene of a bungled car heist (on the other side of the tracks below, with a long line of people as usual . . . ) :

At some points in the film, it looks like "House of Bath-towels" instead of Bamboo:

Fuller sets up a shot:

these black-and-whites don't do justice to the outrageous colors used in the actual movie, so I'm going to post my own color still shots someday:

Fuller continues:

Fuller recalls his last meeting with Yamaguchi in 1990, 35 years after House of Bamboo was made:

x--x--x--x--x

Photo taken at the time House of Bamboo was filmed: another remarkable image of Yoshiko in her prime. Her presence is palpable, impeccable, proud, and unbowed. Perhaps the expression on Yoshiko's face conveys her thinking "you have no idea who I am and what I've been through"

the wood paneling seen here is the same paneling used in the House of Bamboo interior shots - perhaps an attempt by some hapless set designer in Los Angeles to imitate the interiors of a Japanese house.

read about the Kobal Collection here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Kobal

below: at La vie in Rose, a New York nightclub:

on the cover of a Yugoslav(!) film magazine:

and on a Brazil cover:

http://losthorizon.org/1956/Shangri-La.htm

1956 Stage Play: Shangri-La. Musical.

Book by James Hilton, Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee. Based on the novel "Lost Horizon" by James Hilton. Produced by Robert Fryer and Lawrence Carr.

Music by Harry Warren. Lyrics by James Hilton, Robert E. Lee and Jerome Lawrence. Musical Director: Lehman Engel. Choral arrangements and musical continuity by Lehman Engel. Music arranged by Philip J. Lang. Ballet music composed and arranged by Genevieve Pitot. Additional dance arrangements by John Morris. Choreographed by Donald Saddler. Scenic Design by Peter Larkin. Directed by Albert Marre.

Winter Garden Theatre: 13 Jun 1956- 30 Jun 1956 (21 performances).

Cast: Jay Bacon (as "Singer"), Ralph Beaumont (as "Dancer"), Edward Becker (as "Singer"), Sara Bettis (as "Singer"), Elizabeth Burgess (as "Singer"), Jack Cassidy (as "Charles Mallinson"), Joan Cherof (as "Singer"), Robert Cohan (as "The Dancer Perrault"), Michael De Marco (as "Dancer"), Kaie Deei (as "Chao-Li"), Ray Dorian (as "Dancer"), Sylvia Fabry (as "Singer"), Walter Farrell (as "Singer"), Alice Ghostley (as "Miss Brinklow"), Martyn Green (as "Chang"), Eddie Heim (as "Dancer"), Dorothy Hill (as "Dancer"), Joan Holloway (as "Rita Henderson"), Ed Kenney (as "Rimshi"), Dennis King (as "Hugh Conway"), Berry Kroeger (as "High Lama"), Harold Lang (as "Robert Henderson"), Carol Lawrence (as "Arana"), George Lenz (as "Singer"), Greb Lober (as "Dancer"), Ellen Matthews (as "Dancer"), Leland Mayforth (as "The Little One") [Broadway debut], Bob McClure (as "Singer"), David McDaniel (as "Singer"), Teresa Montes (as "Singer"), Eileen Moran (as "Singer"), Illona Murai (as "Dancer"), Mary Ann Niles (as "Dancer"), Jack Rains (as "Singer"), Rico Riedl (as "Dancer"), Edward Stinnett (as "Dancer"), Ed Stroll (as "Singer"), Ted Wills (as "Singer"), Maggie Worth (as "Singer"), Doris Wright (as "Dancer"), Shirley Yamaguchi (as "Lo-Tsen"), Edward Kim (as "Ying Ti"), Marvin Zeller (as "Singer").

“Miss Yamaguchi has the flowing rhythms, the delicacy of manner and the artistic disciplines that bring ‘Shangri-La’ alive,” wrote the New York Times theater critic Brooks Atkinson. The Broadway of The New York Times Book of Broadway "is a shifting, even chimerical phenomenon. It may take its name from something as specific and substantial as the arterial avenue that runs diagonally through Manhattan. But Broadway the theatrical mecca—a name to be writ in flashing neon and pronounced with a drum roll—is too mythic to be confined by geography. It belongs on the same map that includes Camelot, Brigadoon and Shangri-la. The idealized, glamorous Broadway—in which the theater was the city’s heart and a new play opened every night—existed, if ever, only briefly."

from "The Complete Book of 1950s Broadway Musicals"

another Hong Kong film: Mysterious Beauty:

1956:Legend of the White Serpent or Madame White Snake; taken from a traditional Chinese folk-tale:

Buruma used the above glaring head-shot in his 1989 Interview magazine article, calling the picture a "Eurasian fantasy". However, few if any of the Oriental audience watching the film thought of her as a eurasian fantasy, which says something about his visceral dislike of Li Xianglan. (Ed: he might just as well have used a movie-still of her smoking a cigarette and then accused her of being "a bad woman" in real life).

x--x--x--x--x

1957: movie The Unforgettable Night:a final film wrap party:

a center-fold shot:

in an uncharacteristic pose in 1957, and she looks like she means business:

a film poster from the Thai movie "Anchor Wat":

1958: Yoshiko Yamaguchi retired from the world of film at age 38 in order to become the full-time wife of her second husband, a diplomat named Hiroshi Otaka.

Concerning the 1950 thru 1956 phase of her life, Yoshiko says in the Addendum to her memoir "I felt completely exhausted . . . I felt I was a failure in film, on stage, and also in life, and the person who was good enough to encourage and comfort me then was the young diplomat in-the-making. This young man's encouragement became the source of my strength."

She made the above statement following the short-lived run of the Broadway play Shangri-La, after which she found it necessary to spend two weeks in bed due to exhaustion. It's an example of how 'hard' Yoshiko was on herself, and how unrealistically high a bar she had set for herself. Any New York girl would have been ecstatic to become the 'It Girl' of the moment as she had, appearing in all the magazines, newspapers, radio shows, TV shows, parties, and the socialite world of the 1950's. Here she was competing successfully on the international stage, at well over the age of thirty against younger and more 'sexy' girls (who were only too ready to give their all to attain success), and yet Yoshiko felt like a failure!

February 1958: a fan who saw her on a movie-set in Hong Kong writes that she was still "outrageously beautiful":

Yoshiko and Setsuko:

Setsuko Hara (1920 - 2015) :: here is her obituary originally published by the Washington Post titled: "Acclaimed Japanese film actress"http://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-me-setsuko-hara-20151128-story.html

Of particular note is the obvious appreciation and admiration which the obit writer (Adam Bernstein) has for Setsuko, while only mentioning the p word (propaganda) only once in his tribute to her career.

x--x--x--x--x

.jpg)

Did Yao Li make a statement to the press on the occasion of Li Xianglan's passing in Sep 2014? I think they were friends based on the number of photographs of them together. Yao Li's brother, Yao Min, also composed many of Li Xianglan's Mandarin hit songs, he is pictured to the right in the photo of Li Xianglan, Yao Li, and Zhang Lu hooking arms. Now, Yao Li is the last surviving member of the Seven Great Singing Stars of China. -Eddie

ReplyDeleteBack in 1955, House of Bamboo was criticized by the Japanese for being unauthentic, despite employing a Japanese actress. Recently, I saw a comment that it was a propaganda film for US occupation of Japan. I don't totally agree, I think the author was reflecting on Ms. Yamaguchi's early roles in Manchuria. Despite it's shortcomings, House of Bamboo is one of the only color films of Ms. Yamaguchi that is available on DVD in the USA. I wished she sang a song in the gangster dinner party, but it never happened. -Eddie

ReplyDeleteDespite what the director (of House of Bamboo), Sam Fuller, said. Mariko and Eddie had a platonic relationship in the film. Mariko agreed to act as Eddie's kimono to enhance his reputation among the gangsters. At the end of the film, I think most of the audience were hoping that Eddie would realize that Mariko was meant for him and he should return to sweep her off her feet. No Madame Butterfly here. Unfortunately, life was not that simple or ideal for Yoshiko and Isamu. I read that Isamu blamed his divorce on the lack of time the couple spent together. However, your biography mentions Isamu's overbearing opinion on art and aesthetics and the cultural divide between West and East as contributing factors. -Eddie

ReplyDeleteEddie, Thank you for all your various comments! they add to our understanding of Yoshiko in her 'east meets west' ambassadress role.

ReplyDeleteMy favorite film is "Japanese War Bride" even though it was a B&W film; King Vidor was a very different personality from Sam Fuller. Brought up in New York and becoming an infantry soldier in WW2, Fuller had personally killed enemy soldiers and was seared for life by his experiences, which is why his films have the unfortunate 'noir' characteristics they do. King Vidor on the other hand had an interesting business background in Shanghai, and his portrait of life in Salinas is very real.

One can find both these films on sites such as amazon.com where they frequently appear in new, used and good condition.

If life or Broadway had turned out differently we may have had Shirley Yamaguchi as Mei-Li in the Flower Drum Song instead of Miyoshi Umeki. It is not that Miyoshi is not talented, but she was so Japanese, and Shirley would have made a credible Chinese character. It turns out that C.Y. Lee, the author of the Flower Drum Song and Li Jinguang, the composer of The Evening Primrose are brothers. I also read that Yoshiko vowed not to use the name Li Xianglan after her return to Japan. However she made exceptions when she stared in Chinese movies for the Shaw Bothers and made Mandarin Language recordings in Hong Kong in the mid 1950s. I am surprised that as late as 1966 she signed the dog walking photo as Li Xianglan, but that was before she became a journalist and senator. -Eddie

ReplyDeleteRecently, there was an event held in Hong Kong that exhibits rare pictures and movie magazines of Yoshiko Yamaguchi.

ReplyDeleteThose images were mostly pictures of Yamaguchi while she was working in Hong Kong with Shaw Studio. But there were also other interesting images of Yamaguchi as well.

pictures and movie magazines are uploaded online provided by HK01 (media company): http://www.hk01.com/media/webassets/campaigns/2016/space/lixianglan.pdf

PS: I am a Hong Konger and I can speak perfect Cantonese and fluent mandarin. So if anything needs to be translated from Chinese to English, please let me know and I will happy to do so:)

Kit Yu Lui:

ReplyDeleteThank you very much! - if you will forward your email address to me (by unpublished comment) I would appreciate it. Thanks for the link to 85 pages of Li Xianglan pictures and memorabilia!

John M.

I don't have much to comment other than that I am so glad you took the time to write so much about Li Xianglan. My parents grew up listening to her music but albeit don't know anything about her. Her life is very interesting and I'm so glad you've uncovered and translated as much documentation of her life as possible.

ReplyDelete