Sometime during this period of her life, Yoshiko posed for this most beautiful set of photos. in my eyes her smile even exceeds that of the famous Mona Lisa of Leonardo da Vinci:

The 1943 year was extremely busy for Yamaguchi; she appeared in the movies Sayon's Bell, Chorus of Prayer, The Fighting Street, My Nightingale, and Glory to Eternity.

And of course there also were also music hits: this one is "When Will You Return" (He'ri jun zai lai):

however, as Yoshiko writes, "the song's popularity was short-lived, as both my Japanese and Chinese versions of the song were banned because the censors felt that such a song celebrating free love from a foreign country would surely corrupt public morals." [Ed. just another one of Yoshiko's many achievements!]

to the unknown photographer and film-processor who captured these images: So well-done!

x--x--x--x--x

The 1943 year was extremely busy for Yamaguchi; she appeared in the movies Sayon's Bell, Chorus of Prayer, The Fighting Street, My Nightingale, and Glory to Eternity.

And of course there also were also music hits: this one is "When Will You Return" (He'ri jun zai lai):

however, as Yoshiko writes, "the song's popularity was short-lived, as both my Japanese and Chinese versions of the song were banned because the censors felt that such a song celebrating free love from a foreign country would surely corrupt public morals." [Ed. just another one of Yoshiko's many achievements!]

Fan-Club

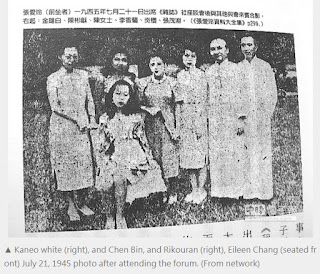

In her memoirs, Yamaguchi mentions a 'fan-club' made up of mainly well-known and powerful men of the time. Herewith is a very rare picture which may show that actual fan-club:

the 1943 film My Nightingale:

a link to the movie (provided by alert reader Peter Z.): 私の鶯 My Nightingale 1943

shot over a 2 year period (mainly in Harbin), it became a true 'phantom film' as it was never released. Made with Japanese, Chinese, and Russian actors and directed by talented Man'ei directors, it was a true 'friendship film' and everyone got along famously. The dialogue was in Russian, which everyone learned to speak passably.

In fact, My Nightingle is barely acknowledged in Japanese film history to this day, even though it was a historic 'art-film' of high calibre, and one of the first authentic Japanese musicals:

The movie cost about five times that of an average film! And what's sad is that the original print lasting two hours may have been lost for all time!

here's Yoshiko with the Russian co-star who plays her father:

If you search Google for "Rakuten Yoshiko Yamaguchi Nightingale" however, you can find this VHS version of it for only $250.01 (if it's available at all):

Fortunately for us, YouTube has rescued the beautiful (Hattori-composed) Russian theme-song of this movie: does Yoshiko enjoy singing this or what?

https://youtu.be/Y0W99Q0rmtc

https://youtu.be/Avvmz_De3YA

another song from "My Nightingale": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6vwdcyRlp4I

Yoshiko recounts that during winter-time, the cast would have a great time taking horse-drawn sleigh-rides through the countryside (like below). Although, when the temperature got too low, the camera would need to be heated on a stove in order to continue filming!

Spying: it turns out that both Japan, China and Russia (and who else?) had agents (spies) keeping tabs on this film because of the many personalities of different cultures involved in it's production.

the 1943 film My Nightingale:

a link to the movie (provided by alert reader Peter Z.): 私の鶯 My Nightingale 1943

shot over a 2 year period (mainly in Harbin), it became a true 'phantom film' as it was never released. Made with Japanese, Chinese, and Russian actors and directed by talented Man'ei directors, it was a true 'friendship film' and everyone got along famously. The dialogue was in Russian, which everyone learned to speak passably.

In fact, My Nightingle is barely acknowledged in Japanese film history to this day, even though it was a historic 'art-film' of high calibre, and one of the first authentic Japanese musicals:

The movie cost about five times that of an average film! And what's sad is that the original print lasting two hours may have been lost for all time!

here's Yoshiko with the Russian co-star who plays her father:

If you search Google for "Rakuten Yoshiko Yamaguchi Nightingale" however, you can find this VHS version of it for only $250.01 (if it's available at all):

Fortunately for us, YouTube has rescued the beautiful (Hattori-composed) Russian theme-song of this movie: does Yoshiko enjoy singing this or what?

https://youtu.be/Y0W99Q0rmtc

https://youtu.be/Avvmz_De3YA

another song from "My Nightingale": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6vwdcyRlp4I

Yoshiko recounts that during winter-time, the cast would have a great time taking horse-drawn sleigh-rides through the countryside (like below). Although, when the temperature got too low, the camera would need to be heated on a stove in order to continue filming!

Spying: it turns out that both Japan, China and Russia (and who else?) had agents (spies) keeping tabs on this film because of the many personalities of different cultures involved in it's production.

x--x--x--x--x

Sayon's Bell (Sayon no kane) was the story of a native Taiwanese girl:the complete Sayon's Bell movie:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LFvYUUwig00

It appears from her exuberant abandon that Yoshiko completely enjoyed playing the role of an aboriginal Taiwan girl in this film! Whether it was calling and chasing pigs, poling a bamboo raft, or handling children and babies, she expresses a true joy in the simple pleasures:

While chasing this wild-pig, Yoshiko shows how daring she was!

The movie was shot on location in Taiwan and in retrospect is a beautiful image of this mountain village, almost a documentary of the village life, showing the handiwork of farming, spinning, weaving, milling grain, and typical village animals like chickens, pigs and geese. I admire how the film-makers showed these every-day aspects of living in such a normal manner.

Yoshiko always had obligations to perform for the Japanese military, as shown by the below Taiwan-Japanese Army song:

the same military song in the Sayon's Bell movie:

The scene where Yoshiko happily sings the Sayon's Bell theme song as she herds a gaggle of geese towards a camera moving backwards up the road is quite memorable:

Yoshiko writes about how during the shooting of this film, she was treated with great hospitality by the aboriginal people because she so resembled the chief's daughter! They honored her by performing a head-hunting dance ceremony around a roaring bonfire, which she says in fact really "terrified" her.

There is controversy even today regarding the fact that the Sayon's Bell script was based on an actual event which was 'twisted' in order to conform with Japanese 'national film policy' as it applied to Taiwan. This video (and below column) makes the case:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kUAykNHTG0g

Taiwan (like Korea) was a protectorate of Japan since the early 1900's (although such words as 'protectorate', 'mandate', or 'trust territory', do not fully convey the complexity of the situation for everyday people):

x--x--x--x--x

1943: the film Glory to Eternity or Eternal Fame (Wanshi Liufeng) opens in Shanghai.

This was a very important film in Yamaguchi's career. Prior to it, she was popular mainly in Manchuria and Japan, and this film actually was her debut into the mainstream Chinese market covering the whole continent. Unlike her prior films which were made by Man'ei or various Japan-based film companies, Eternity was essentially made by Chinese*. Further, she more than 'held her own' in the company of the most prominent Chinese actors and actresses of the time. Above photo and others below are with her co-star Chen Yunchang.

*ie, those Chinese who were skillful enough to satisfy Japanese military censorship on one hand, and the Chinese citizenry on the other. It was not an easy task, and Yamaguchi comments "men of conscience were doing their very best under the most trying [wartime] conditions."

1942 marked the centennial of the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing which a humiliated entity called China was forced to sign following defeat by the British in the Opium War.

The film Glory to Eternity was named thusly to memorialize the exploits of the heroic Lin Zexu in his struggles against the British while fighting against the pernicious effects of opium.

below is a 26 minute video of Yoshiko's singing and acting in the 1943 film Glory to Eternity.

Those critics who have summarized Yoshiko's whole career with the three words "propaganda film actress" should be ashamed of their shoddy scholarship - this clip shows how and why she should be remembered for Eternity.

-the clip represents the very high-point of Yoshiko's movie career in mainland China - Enjoy!:

the below music video contains many shots of the principals in Eternity:

Concerning Eternity's plotline, Yamaguchi says it was cleverly written with the idea of "borrowing from the past to ridicule the present". In this case it meant using a famous Chinese story from the Opium War of 1842 to allegorically criticize the 1942 Japanese. It was meant to be a patriotic film driven by nationalistic sentiments, with it's theme of exhorting China to rise up as a nation: this is why it was enormously popular with all Chinese, so much so that they would stand up en-mass in the theater and clap their approval at various times in the film.

Yoshiko says the following about Chen Yunchang: "as the leading actress of her generation, she made no attempt initially to conceal her displeasure and treated me with guarded caution, suspecting I was Japanese. However, after living with me for awhile, she began to notice how different I was from the average Japanese and gradually warmed up to me as a consequence." These pictures show this very well indeed.

A well-known prior example of a patriotic film like Glory to Eternity was Mulan Joins the Army, (also starring Chen Yunchang) the story of a Chinese girl who dresses as a boy and joins the army, and thereby scores a great victory for her country. Glory to Eternity was a huge hit when it was released in June 1943, garnering the largest audience in Chinese film history. As an example of Li Xianglan's popularity in the film is the below cigarette package, which was named "Li Xianglan" and "National Resistance" [Ed: ie, resist the Japanese invader!]

you can play her famous "Quit Smoking" song from this sheet:

(above passage by Yiman Wang in the book "Sino-Japanese Transculteration".

(above passage by Yiman Wang in the book "Sino-Japanese Transculteration".The fact that the film "Eternity" basic story-line was strongly anti-imperialist (and hence anti-Japanese as well) seems to have eluded Ms. Wang).

however, the best review and insights regarding the film "Eternity" were written by the great writer Eileen Chang:

x--x--x--x--x

One of the more humorous episodes in Yoshiko's Shanghai memories occurs when she tells the story of how "one of the Japanese army big-shots" demanded she join him at a local tea-house: when she refuses his invitation he is so miffed that he actually had the place burned to the ground! It's stories like this one that endeared her to her Chinese co-workers on the set of Eternity, while at the same time adding to the hatred of the Japanese military. Link to 78 still photos of the movie.

x--x--x--x--x

A last look at Li Xianglan singing in Eternity, as quoted in this work:http://www.japansociety.org.uk/29953/my-life-as-li-xianglan/

Yamaguchi as Li Xianlang was propelled to stardom with movies including “Leaving a Good Name for Posterity” about the Opium War. It was produced in Shanghai by a joint venture between Japanese and Chinese as Japanese propaganda. The head of the production company, Kawakita Nagamasa, was a veteran in the film industry and chose themes that passed Japanese military censorship but appealed to Chinese audiences. In this movie, the Chinese understood that British colonial ambitions in China had been parallel to modern Japanese ambitions. General Lin Zexu who fought against British was a national hero. Li Xianglan appeared as a girl selling candy in the opium dens, and exhorts them to "stop smoking my dears".

Wikipedia summarizes Eternity:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoshiko_Yamaguchi

In 1943, Yoshiko appeared in the film Eternity (萬世流芳). The film was shot in Shanghai commemorating the centennial of the Opium War. A few top Chinese stars in Shanghai also appeared in the film and consequently endured the repercussion of controversy. Though the film, anti-British in nature, was a collaboration between Chinese and Japanese film companies, its anti-colonization undertone might also be interpreted as a satire of the Japanese expansion in east Asia. Despite all this, the film was a hit and Yoshiko became a national sensation.

"Eternity" had two hit songs: "Candy-Peddling Song" (賣糖歌) and "Quitting Opium Song" (戒煙歌), they elevated her status to among the top singers in all Chinese-speaking regions in Asia overnight.

another contemporary review of "Eternity" (by Eileen Chang) which you may find interesting:

https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10524/32551/1/79-Volume4.pdf

Totally exhausted from film work toward the end of 1943, Yoshiko just wanted to rest although thoughts about retiring from the film industry were going through her mind.

She was experiencing ever greater guilt and misgiving over her Li Xianglan name, especially as close Chinese friends were beginning to disappear into the underground resistance movement. One such example was her best friend (Wen Guihua) from the Yijiao Girl's School in Beijing, who made a long and dangerous trip through Japanese occupied territory to reach her boyfriend who was in the underground; some forty-four years later this couple had survived to live in Taiwan.

"Today I don't want to hold back anything anymore. May I say at the outset that Li Xianglan is really Yamaguchi Yoshiko, a Japanese woman who was born in China and loves China?"

Mr. Li shakes his head and strongly disapproves her demand: "I am absolutely against it. There may be some Chinese who know exactly who you are, but even they won't acknowledge the fact. You are Chinese and a star that we and Beijing produced; I don't want you to shatter our dreams. You must present yourself as Chinese!"

The press conference proceeded in a friendly manner discussing various aspects of the Glory to Eternity film. Just when it seemed to be over and safety had been reached, a young reporter with expert timing sharply interrupted Mr. Li's closing words: "Miss Li Xianglan! I wish to ask you one last thing." Yamaguchi's heart skipped a beat, she knew this would happen. The young reporter wanted to know what her real intentions had been in making 'Japanese films' like Song of the White Orchid and China Nights, which could be taken as insults to the Chinese. The journalist asks “You are Chinese, aren't you?" and "Where is your pride as a Chinese?”

Yamaguchi writes that at this point, she almost confessed she was born a Japanese. Seconds tick by as her mind grappled for an answer to the young reporter's excellent questions. But the pressure on her not to disclose her true identity had been applied by different groups who all had an interest in her remaining silent.

She bowed deeply to the journalists, saying "it was a mistake I made before the age of twenty when I was young and unaware of the full situation. I made this mistake out of ignorance and I regret it today. Please forgive me. I will not make the same mistake again."

The assembled journalists applauded her response. By asking her "you are Chinese, aren't you?", the young reporter confirms what most people already suspect about Li Xianglan, ie, that she is of mixed parentage:

She was experiencing ever greater guilt and misgiving over her Li Xianglan name, especially as close Chinese friends were beginning to disappear into the underground resistance movement. One such example was her best friend (Wen Guihua) from the Yijiao Girl's School in Beijing, who made a long and dangerous trip through Japanese occupied territory to reach her boyfriend who was in the underground; some forty-four years later this couple had survived to live in Taiwan.

x--x--x--x--x

Yamaguchi recalls a 1943 press conference in Beijing shortly after Eternity was released. Prior to appearing in front of about fifty journalists, she discussed her wish to finally reveal herself with one Mr Li, the head of the Press Club (and also a friend of her father, Fumio). "Today I don't want to hold back anything anymore. May I say at the outset that Li Xianglan is really Yamaguchi Yoshiko, a Japanese woman who was born in China and loves China?"

Mr. Li shakes his head and strongly disapproves her demand: "I am absolutely against it. There may be some Chinese who know exactly who you are, but even they won't acknowledge the fact. You are Chinese and a star that we and Beijing produced; I don't want you to shatter our dreams. You must present yourself as Chinese!"

Yamaguchi writes that at this point, she almost confessed she was born a Japanese. Seconds tick by as her mind grappled for an answer to the young reporter's excellent questions. But the pressure on her not to disclose her true identity had been applied by different groups who all had an interest in her remaining silent.

She bowed deeply to the journalists, saying "it was a mistake I made before the age of twenty when I was young and unaware of the full situation. I made this mistake out of ignorance and I regret it today. Please forgive me. I will not make the same mistake again."

The assembled journalists applauded her response. By asking her "you are Chinese, aren't you?", the young reporter confirms what most people already suspect about Li Xianglan, ie, that she is of mixed parentage:

x--x--x--x--x

Yamaguchi traveled to North Korea to make a short appearance in a film called Soldiers (perhaps called Field Army Orchestra in her memoir): the camera-work is just superb in this clip:

What was the 24yr old Li Xianglan like in person?

An interview with her was published in Sep/Oct 1944 (see Stephenson "Her Traces" p.231).

I paraphrase it thusly: The interviewer is quite impressed with Li Xianglan's energy and movement. Li meets her at the door in her pajamas, not having changed yet:

"So fast that I almost didn't see the dazzle of those pretty red pajamas, like lightning she entered a side room. Later, having changed clothes she came out, but she didn't settle down at all. She laughs and asks for my opinion, and before I can answer, calls to the amah (maid) for food and cool drinks, and then, amidst many 'excuse me, excuse me's', she finally sits down. And throughout the interview, the star is constantly moving: looking up at the ceiling while answering a question, squeezing her handkerchief, fluttering her eyelashes, fixing her hair, jumping up to answer phone calls or get more drinks."

"So fast that I almost didn't see the dazzle of those pretty red pajamas, like lightning she entered a side room. Later, having changed clothes she came out, but she didn't settle down at all. She laughs and asks for my opinion, and before I can answer, calls to the amah (maid) for food and cool drinks, and then, amidst many 'excuse me, excuse me's', she finally sits down. And throughout the interview, the star is constantly moving: looking up at the ceiling while answering a question, squeezing her handkerchief, fluttering her eyelashes, fixing her hair, jumping up to answer phone calls or get more drinks."

Stephenson then remarks that the above minutiae of detail is more typical of articles about Li Xianglan than about any other stars [and to this I say of course! it was the result of Li Xianglan's charisma, not some dark plot of the Japanese 'national film policy'].

Most interesting also is Stephenson's description of a cartoon about Yamaguchi which appeared alongside a 2 page article on "Eternity" in Feb 1943. The cartoon depicts Li Xianglan (the "goldfish beauty") with enormous eyes, dressed in her ubiquitous cheongsam, carrying a suitcase plastered with travel stickers while striding across the Asian nations on a globe below her feet. Under her feet are also the characters for 'East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere'. So everyone was aware of the so-called 'propaganda' that Li Xianglan was promoting, and it was an open secret, or even a public item of amusement in this cartoon.

In the above Sep/Oct 1944 interview, Li Xianglan says "Really, speaking honestly, because of these films [like China Nights], I have always felt that I have let us Chinese people down". The fact that she said "let us Chinese people down" should be accepted at face value - she honestly felt Chinese.

x--x--x--x--xYamaguchi traveled to North Korea to make a short appearance in a film called Soldiers (perhaps called Field Army Orchestra in her memoir): the camera-work is just superb in this clip:

This film 「兵隊さん」 (Heitaisan) was _discovered_ in 北京 in 2006.

In 2009, 한국영상자료원 (韓國映像資料院) remastered the film and released it on DVD.

The language spoken in the movie is entirely Japanese. The location is Korea.

In the scene here, soldiers are enjoying live performances of music & dance during their training life.

李香蘭 appears as the last performer for 1 min 30 sec.

Soldiers are Korean and Japanese, and the place you see is the training school. Here she is during the filming of another picture (Kimi to Boku):

If anyone is doing research on the above movie and reads Baskett's "Attractive Empire" page 87, they might get a kick out of how he notes that Yi Hyang-ran (a bad translation of Li Xiang-lan) is a "Korean top-box office star"!

The army in Korea (朝鮮軍) started recruiting volunteers (志願兵) in 1938, and started conscription (徵兵) in 1944.

Here is a film on volunteers in Korea:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1dTBnLJwr4

(remarks courtesy of 'oldindrub')

some history of "Korea as a Protectorate of Japan":

http://www.pennfamily.org/KSS-USA/hist-map9.html

the Koreans (also) thought Yoshiko was one of their own people:

In autumn of 1944, Yoshiko finished shooting "Field Army Orchestra".

here's a full-throated song from that movie:

She then has a meeting with Masahiko Amakazu (Director of Man'ei) and tells him "I can no longer pretend I am Chinese. I have found myself squeezed between Japan and China, and it's become unbearable for me. I hope you'll rescind my contract." This was not a trivial request, because Masahiko had been responsible for a lot of mayhem in his life, and who knows what he could have done, given what he was capable of doing.

However, quite the gentleman at this point, he replies "I understand perfectly. Thank you for all your hard work over the years," and then he adds "I have no idea what Manchukuo and Man'ei will become, but you have a long future ahead; let your own wishes be your guide. If you do decide to work in Japan, I'm sure there will be many difficult moments for you. Take good care of your health and follow your heart." Amakasu must have seen the end coming for Japan's 40 year 'continental dreams' when he expressed the above to Yamaguchi.

Nine months later, he would take his own life as the Soviet army entered Xinjing following Japan's surrender in August of 1945.

After resigning from Man'ei at end of 1944, Yamaguchi lived in Shanghai where there still was some film activity going on (despite the war approaching ever closer to the city limits). She was tentatively selected to star in several movie projects but these eventually were all cancelled. Li Xianglan had planned to 'come out' as a Japanese following these movies, but for one reason and another, these plans were put on hold.

War was coming closer as the Japanese were pushed back towards the coast. The Imperial Japanese Navy ship Izumo with the Bund in background:

Yoshiko recalls how one of the beautiful Chinese stars in "Eternity" was forced to present the Izumo captain with a big bouquet of flowers, giving the newspapers a propaganda photo (which everyone who saw it knew was propaganda). The young Chinese star (most likely Chen Yunchan) wept whenever she recalled the humiliating situation.

At this time Yamaguchi lived at the exclusive Broadway Mansions hotel (tall building below) by the Huangpu river:

looking towards the Bund district (perhaps similar to the view from Li Xianglan's apartment):

here's one of the best panorama pictures of the Bund as it was then:

http://uetoayarikoran.cocolog-nifty.com/photos/uncategorized/photo_36.jpg

Broadway Mansion Hotel History:

The hotel, completed in 1934, was built by the British as an exclusive residential hotel under the English name, Broadway Mansions. Located near Shanghai's Little Tokyo, it immediately became the headquarters for Japanese commercial activities. The Japanese military commandeered it in 1937 for the headquarters of the Japanese Army Liaison Office when Japan invaded China, even though they did not at that time take over the Shanghai International Settlement, which included the Bund. A Japanese stock company purchased the hotel in 1939 for about half of its $3.4 million (US) cost of construction.

At the end of WWII, ownership was transferred to the Shanghi Municipal Counsel, and it became the headquarters for the American Military Mission, and the residence of a number of US Army officers, with an Army hospital on the ground floor. The top four floors became the residence for members of the Foreign Correspondents' Club of China, from which they covered the end of Chinese Civil War and the founding of the People's Republic of China. The army left, but the journalists remained until they were ousted by the new government.

Shanghai of 1945 (courtesy of the U.S. Army):

In late 1944, Yoshiko recorded two songs composed by Masao Koga which were 'test recordings' and never released to the public. They were found in a large wooden trunk a few years ago as recounted by the following Kyodo News item:

And here are the 2 songs.

and the record as it appears today in the Koga Music Museum:

Found it all: 2 compositions in a large wooden chest, composed by Masao Koga (古 賀 政 男) "Cloudy Hometown" (雲 の ふ る さ と)and "Moonlight droplets" (月 の し ず く) '. According to the history of Colombia and Japan as a test plate was recorded in studios in Tokyo in November 1944. [Kyodo News]

June 1945 - the Concert at Shanghai's Grandest Theater

Perhaps due to the general atmosphere of frustration and worry caused by the approaching war's end, all the musical people then came up with the idea of presenting "a grand musical" featuring Li Xianglan (one has to sympathize with how the artists realized their Shanghai world was coming to an end fairly soon, and how this last 'blast' of a musical would be a coda of sorts to that world). The program's songs were arranged by Ryoichi Hattori in the symphonic jazz style of his idol George Gershwin, presenting a glorious amalgamation of eastern and western music. Here is Hattori with Yamaguchi:

The Shanghai Philharmonic orchestra composed of 100 musicians, conducted by Hattori and Chen Gexin, accompanied Li Xianglan at the very height of her career in China. The concert venue was the Grand Theatre:

The Shanghai Grand Theater (called Da'guangming Daxiyuan) was the most elegant in Shanghai and had two thousand plush seats, all of them reserved and sold out for her performances. The below view shows the Park Hotel (mentioned by Yamaguchi's memoirs) in background, with Grand Theater in foreground facing the Shanghai Race Course:

Constructed by the Hungarian architect Laszlo E. Hudec in 1928, the original Shanghai Grand Cinema enjoyed a very long and celebrated history, once dubbed “The Best Cinema of The Far East” by many Westerners who enjoyed attending the theater in the 1930’s and 40’s.

The outer theater was constructed in a very creative and imaginative modern style for the time. The cream-maize colored outer façade took the shape of a full mainsail blowing in the breeze against a crescent wave, accompanied by a brilliant water lily shaped three-tier roof. Meanwhile, the inner theater was marked by the opulence of crystal chandeliers and imported Italian marble, which gave the theater an elegant feel. These features made attending the Grand Cinema quite the status symbol among Shanghai’s elite during the theaters early years.

On top of the theater's luxurious and graceful style, the Grand Cinema has also benefited from a long history of creativity and innovation in the industry. In 1939, the theater installed a simultaneous translation system which placed a personal earpiece in each of the main theater’s then 1,913 seats. The owners of the Grand Cinema would hire a translator to narrate and interpret the dialogue of the Western movies to the largely Chinese audience.

The cinema was also marked by a series of firsts. For example, it was the first theater to offer widescreen viewing as well as the first to introduce a stereo system. And it had air-conditioning!

The Grand Theater as it appears today:

the lobby, newly renovated in 2008:

a site having 30 pictures of the theater, interior and exterior:

http://shjytan.cn/8c60ba86c/

newly renovated:

and as it appeared during Yoshiko's visit in 1998:

It's a shame we don't have a recording of this almost final Yamaguchi performance in Shanghai! But I did find this amazing performance (complete with full orchestra) of the Hattori Night Fragrance Fantasia in the style of Gershwin. And it is exactly as Yamaguchi described it in her memoir, a riotous amalgamation of western and oriental music styles (the elderly Hattori himself is shown in the opening scenes): enjoy!

https://youtu.be/j4OCKoqsoD4

and we do have the re-enactment of Aya Ueto (2007 Fuji TV movie) which conveys the concert atmosphere very well:

https://youtu.be/MbUmhMPutEE

Held in June 1945 over a three day period (23rd, 24th, and 25th), there were two shows each day for a total of six performances of "The Evening Primrose Rhapsody". Every show was sold out. Scalpers were charging three times the face value of tickets because of the demand. Management asked Li Xianglan to perform for another week but she declined because of the stress on her vocal-chords.

In 2009, 한국영상자료원 (韓國映像資料院) remastered the film and released it on DVD.

The language spoken in the movie is entirely Japanese. The location is Korea.

In the scene here, soldiers are enjoying live performances of music & dance during their training life.

李香蘭 appears as the last performer for 1 min 30 sec.

If anyone is doing research on the above movie and reads Baskett's "Attractive Empire" page 87, they might get a kick out of how he notes that Yi Hyang-ran (a bad translation of Li Xiang-lan) is a "Korean top-box office star"!

The army in Korea (朝鮮軍) started recruiting volunteers (志願兵) in 1938, and started conscription (徵兵) in 1944.

Here is a film on volunteers in Korea:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1dTBnLJwr4

(remarks courtesy of 'oldindrub')

some history of "Korea as a Protectorate of Japan":

http://www.pennfamily.org/KSS-USA/hist-map9.html

the Koreans (also) thought Yoshiko was one of their own people:

In autumn of 1944, Yoshiko finished shooting "Field Army Orchestra".

here's a full-throated song from that movie:

She then has a meeting with Masahiko Amakazu (Director of Man'ei) and tells him "I can no longer pretend I am Chinese. I have found myself squeezed between Japan and China, and it's become unbearable for me. I hope you'll rescind my contract." This was not a trivial request, because Masahiko had been responsible for a lot of mayhem in his life, and who knows what he could have done, given what he was capable of doing.

However, quite the gentleman at this point, he replies "I understand perfectly. Thank you for all your hard work over the years," and then he adds "I have no idea what Manchukuo and Man'ei will become, but you have a long future ahead; let your own wishes be your guide. If you do decide to work in Japan, I'm sure there will be many difficult moments for you. Take good care of your health and follow your heart." Amakasu must have seen the end coming for Japan's 40 year 'continental dreams' when he expressed the above to Yamaguchi.

Nine months later, he would take his own life as the Soviet army entered Xinjing following Japan's surrender in August of 1945.

After resigning from Man'ei at end of 1944, Yamaguchi lived in Shanghai where there still was some film activity going on (despite the war approaching ever closer to the city limits). She was tentatively selected to star in several movie projects but these eventually were all cancelled. Li Xianglan had planned to 'come out' as a Japanese following these movies, but for one reason and another, these plans were put on hold.

War was coming closer as the Japanese were pushed back towards the coast. The Imperial Japanese Navy ship Izumo with the Bund in background:

At this time Yamaguchi lived at the exclusive Broadway Mansions hotel (tall building below) by the Huangpu river:

the stolid Garden Bridge today is an architectural and historical landmark of Shanghai:

the Broadway Mansions building is on the right in this well-known Shanghai photo:

looking towards the Bund district (perhaps similar to the view from Li Xianglan's apartment):

http://uetoayarikoran.cocolog-nifty.com/photos/uncategorized/photo_36.jpg

Broadway Mansion Hotel History:

The hotel, completed in 1934, was built by the British as an exclusive residential hotel under the English name, Broadway Mansions. Located near Shanghai's Little Tokyo, it immediately became the headquarters for Japanese commercial activities. The Japanese military commandeered it in 1937 for the headquarters of the Japanese Army Liaison Office when Japan invaded China, even though they did not at that time take over the Shanghai International Settlement, which included the Bund. A Japanese stock company purchased the hotel in 1939 for about half of its $3.4 million (US) cost of construction.

At the end of WWII, ownership was transferred to the Shanghi Municipal Counsel, and it became the headquarters for the American Military Mission, and the residence of a number of US Army officers, with an Army hospital on the ground floor. The top four floors became the residence for members of the Foreign Correspondents' Club of China, from which they covered the end of Chinese Civil War and the founding of the People's Republic of China. The army left, but the journalists remained until they were ousted by the new government.

Shanghai of 1945 (courtesy of the U.S. Army):

x--x--x--x--x

And here are the 2 songs.

and the record as it appears today in the Koga Music Museum:

Found it all: 2 compositions in a large wooden chest, composed by Masao Koga (古 賀 政 男) "Cloudy Hometown" (雲 の ふ る さ と)and "Moonlight droplets" (月 の し ず く) '. According to the history of Colombia and Japan as a test plate was recorded in studios in Tokyo in November 1944. [Kyodo News]

for a link to a CD which has these 2 beautiful songs, click http://yoshikoyamaguchi.blogspot.com/p/the-songs.html

x--x--x--x--x

June 1945 - the Concert at Shanghai's Grandest Theater

Perhaps due to the general atmosphere of frustration and worry caused by the approaching war's end, all the musical people then came up with the idea of presenting "a grand musical" featuring Li Xianglan (one has to sympathize with how the artists realized their Shanghai world was coming to an end fairly soon, and how this last 'blast' of a musical would be a coda of sorts to that world). The program's songs were arranged by Ryoichi Hattori in the symphonic jazz style of his idol George Gershwin, presenting a glorious amalgamation of eastern and western music. Here is Hattori with Yamaguchi:

The Shanghai Philharmonic orchestra composed of 100 musicians, conducted by Hattori and Chen Gexin, accompanied Li Xianglan at the very height of her career in China. The concert venue was the Grand Theatre:

The Shanghai Grand Theater (called Da'guangming Daxiyuan) was the most elegant in Shanghai and had two thousand plush seats, all of them reserved and sold out for her performances. The below view shows the Park Hotel (mentioned by Yamaguchi's memoirs) in background, with Grand Theater in foreground facing the Shanghai Race Course:

Constructed by the Hungarian architect Laszlo E. Hudec in 1928, the original Shanghai Grand Cinema enjoyed a very long and celebrated history, once dubbed “The Best Cinema of The Far East” by many Westerners who enjoyed attending the theater in the 1930’s and 40’s.

The outer theater was constructed in a very creative and imaginative modern style for the time. The cream-maize colored outer façade took the shape of a full mainsail blowing in the breeze against a crescent wave, accompanied by a brilliant water lily shaped three-tier roof. Meanwhile, the inner theater was marked by the opulence of crystal chandeliers and imported Italian marble, which gave the theater an elegant feel. These features made attending the Grand Cinema quite the status symbol among Shanghai’s elite during the theaters early years.

On top of the theater's luxurious and graceful style, the Grand Cinema has also benefited from a long history of creativity and innovation in the industry. In 1939, the theater installed a simultaneous translation system which placed a personal earpiece in each of the main theater’s then 1,913 seats. The owners of the Grand Cinema would hire a translator to narrate and interpret the dialogue of the Western movies to the largely Chinese audience.

The cinema was also marked by a series of firsts. For example, it was the first theater to offer widescreen viewing as well as the first to introduce a stereo system. And it had air-conditioning!

The Grand Theater as it appears today:

the lobby, newly renovated in 2008:

a site having 30 pictures of the theater, interior and exterior:

http://shjytan.cn/8c60ba86c/

newly renovated:

and as it appeared during Yoshiko's visit in 1998:

x--x--x--x--x

It's a shame we don't have a recording of this almost final Yamaguchi performance in Shanghai! But I did find this amazing performance (complete with full orchestra) of the Hattori Night Fragrance Fantasia in the style of Gershwin. And it is exactly as Yamaguchi described it in her memoir, a riotous amalgamation of western and oriental music styles (the elderly Hattori himself is shown in the opening scenes): enjoy!

https://youtu.be/j4OCKoqsoD4

and we do have the re-enactment of Aya Ueto (2007 Fuji TV movie) which conveys the concert atmosphere very well:

https://youtu.be/MbUmhMPutEE

Held in June 1945 over a three day period (23rd, 24th, and 25th), there were two shows each day for a total of six performances of "The Evening Primrose Rhapsody". Every show was sold out. Scalpers were charging three times the face value of tickets because of the demand. Management asked Li Xianglan to perform for another week but she declined because of the stress on her vocal-chords.

newspaper ad for the grand concert:

Each performance had three parts. The first part was "Songs from the East and the West" and included Japanese and Western classic favorites. The second part was Chinese songs which included all the latest hits. Chen Gexin was the conductor for parts one and two. The following photos were taken at the concert:

After the above portion finished, it was followed by the sound of an er'hu (Chinese violin) playing "Peddling Evening Primrose", which had been the original inspiration for Li Xianglan's hit song. A Chinese folksong, it's lyrics (in a melancholic prescient fashion) spoke poetically to the audience:

"The beautiful evening primrose blossom, dimly white in the darkness of night, sends forth its graceful scent. Its color and fragrance will shortly fade; let's enjoy its beauty while it lasts. Now is the time to buy them, the evening primrose blossoms."

followed by the string section playing the same song in waltz-time, and as if that was not enough sonic innovation for one song, the finale had everyone moving to an eight-beat boogie-woogie rhythm!

As for how this new beat sounded, listen to Hattori's "Tokyo Boogie Woogie" (with almost 900,000 views!) sung by a dancing Shizuko Kasagi at the Nichigeki theater in 1946:

As anyone can see from this dance-video, risque American tastes were very quickly adopted by a defeated Japan; the colonizing process was just beginning and in full swing. In one of Yamaguchi's movies of 1955 called House of Bamboo, you'll see another outlandish dance scene (I'll post it someday), which in terms of Japan's traditional culture, probably was seen as strangely obscene.

Following Li Xianglan's last performance of the series, the audience was in no mood to leave the theater and they clapped and clapped until she sang an encore song, and then another, and another, until members of the audience began to get on the stage. Two of Shanghai's most famous divas, Bai Hong and Zhou Xuan (see picture at right and below) then came on stage and presented Li with a huge bouquet of flowers and the evening ended with onstage embraces between them all.

http://auction.artron.net/paimai-art0040695792/ (shows magnification of above photo)

someone made this beautiful colorization:

You would think that this curtain-fall on the final show is where this particular story ends, but (like so many stories in Yamaguchi's life) you'd be quite wrong.

You would think that this curtain-fall on the final show is where this particular story ends, but (like so many stories in Yamaguchi's life) you'd be quite wrong. While trying to make her way through the congratulating crowd, who does Xianglan bump into but Lyuba Monosova Gurinets, the same Lyuba that she hasn't seen since her Fengtian days in 1934! Both are astounded: Lyuba endearingly calls her "Yoshiko-chan", and Xianglan calls her "Lyubochka" as they did when they were younger. Lyuba and her parents have come to see the Li Xianglan they once knew as a fourteen year old.

They throw a traditional Russian party for Yoshiko-chan, complete with favorite food she loves to eat: mounds of fried piroshki! When she sees a picture of Stalin hanging on the wall, Yoshiko says "I don't care whether she is White or Red Russian, Lyuba is Lyuba".

Unfortunately, Lyuba's family were communists (the word seems harsh and incongruent now, but during those times it was a word of different importance), and both Lyuba and her father worked for the Soviet Consulate in the area of cultural affairs. Unbeknownst to Yamaguchi, the Japanese Consul was in touch with the Soviets regarding items of mutual interest such as films, etc.

You can understand why Yamaguchi with her excellent linguistic ability and wide circle of friendships of every nationality, was suspected by everyone (especially the Chinese) of transferring information, (otherwise known as spying for the enemy).

In these waning days before defeat, Japan was making diplomatic efforts to reach out to Russia as a possible intermediary in peace talks with the United States and Britain. Yoshiko was enlisted to convey diplomatic messages to her good friend Lyuba; this association would also add to the impression that Yoshiko was a spy and sympathetic to the Communists.

x--x--x--x--x

All of the diligence and hard work she put into her career took it's toll on Li Xianglan's personal life, as she expressed it in a 1945 magazine interview following her smashing performance at the Grand Theater. Participating also in this discussion was the writer Eileen Chang. Quoted from the "Her Traces are Everywhere" chapter by Stephenson in "Cinema and Urban Culture in Shanghai" on p. 244, Li Xianglan revealingly says:

"I wish to discover how to be a person! . . . My ideal, I should be a healthy person - having a healthy body, a healthy life, a healthy love. To be a person without having a healthy life, to me is like not being a [whole] person . . . How to do it, how to be a person? . . . Of course, every day I sing, every day I have teachers teaching me English, Russian, and music. This is study, this is training, but it's not the basic principle behind being a person . . . I don't know how to go about being a person . . . A girl's blessing doesn't consist of fame and fortune . . . of what does it consist? . . . I don't know . . . Coming home from my concert at Shanghai Grand [Daguangming] Theater, all at once I cried, I cried like anything. I feel lonely! . . . My philosophy of life and what I express in films are two different things. . . Sometimes, I really want to do something bad . . . "

Stephenson then comments on the above thusly: "Without the unceasing process of construction of that "character" - that is, without travel and language study and music lessons - there exists in her nothing else. ... The construction of character through the blurring of boundaries may be utopian but it is also, by her formulation, deeply dehumanizing."

It's here that I must respectfully object to Ms. Stephenson's characterization, putting words into Li's mouth. Li said nothing about boundaries and would certainly have objected to being accused of "construction of character" (an outright slur which is typical of Stephenson's type of freighted implications throughout her writings about Li Xianglan).

Li is being quite candid by telling the world "I don't know how to be a [full] person" and "I feel lonely"; in fact, this was merely her way of saying "all work and no play makes Jill a dull girl". To try and twist this as Stephenson has done is sadly the type of 'reaching' scholarship now being applied to Li's life story. Yamaguchi was continually improving herself through education and dedication to harmony in every sense of that word: she was born with character and didn't need to construct it or fake it.

The "constructions" are Stephenson's area of expertise on p. 223:

"the received image of Li Xianglan presents a movie star famous for masquerading on- and off-screen as a Chinese woman"

Li did not masquerade off-screen and she acted the parts in movies that were given her. Li makes very clear in her memoir that in many ways her thinking and personality were more Chinese than Japanese, so Stephenson et al should stop propagating an incorrect image. You have to wonder if people like Stephenson are really annoyed because Yamaguchi did not conform to the received image in the west of a stereotypical Japanese girl. And 'one more thing': how is it that caucasians can point their finger at an oriental personage and presume to know anything about their "real identity", as Stephenson obnoxiously does? If both Japanese and Chinese intellectuals themselves all thought Li was Chinese (the list of such people is very long), it means the Stephenson's of the world are way off base.

Yamaguchi felt very comfortable in a Chinese dress (intellectually and physically) and she looked fabulous in it; perhaps her critics feel threatened because she transcended the ordinary and mediocre notions of nationality which their whole thesis is based on:

on p. 229 "closely tied up with the image of Li Xianglan as a figure absent from the star system in Shanghai is her image as a traveler": Li was absent because she really was traveling.To say "her image as a traveler" is an insult - she was traveling constantly from the age of 18 until quitting movies at age 38 - and she didn't do this to maintain 'an image', she did it to make her daily bread and get from point A to point B.

on p. 232 "role as traveler through her various identities": Please: Roles are played in movies, Li did not play a role in real life, she was not schizophrenic and did not have separate identities. She was lively, beautiful, and multi-talented, which is why she was such a fascinating woman.

But here I want to also praise Stephenson for the many pieces of scholarly information she included in her chapter. One of which is below:

The perception of a writer:

During the above discussion, Eileen Chang praised Li . . . "noting that after hearing Li sing, she could only feel that she's not human but rather some kind of fairy".

a lot has been written about this meeting between Chang and Li. This thoughtful article compares the two.

Eileen seated next to Li Xianglan

(above passage by Yiman Wang)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eileen_Chang

Note: Zhang Ailing (Eileen Chang) has written one of the best 'true-to-life' stories about 1940s Shanghai: Lust Caution. Her story which is loosely based on actual events is the basis of the Ang Lee hit-film of the same name. You can read my research into this fascinating story here:

(still under construction as of 2025.)

During these last few months of mid-summer 1945 prior to Japan's formal acceptance of defeat, everyone in Shanghai with access to short-wave radio or other 'outside information' was aware that the end was indeed near.

One day, Li Xianglan was requested to sing for a group of dignitaries at the Cathay Hotel (built by Victor Sassoon 1929 on the Huangpo River: The Cathay Hotel now called The Peace Hotel:)

As she started to sing, air-raid sirens went off, bombs started falling, and American planes were diving and strafing with machine-guns. Everyone ran down to the basement and huddled in the dark, wondering if they would all be killed by bombs that were shaking the building like earthquakes. This terrifying scene lasted about an hour:

She recalls with horror the sight from an upper floor: of "heaps" of dead bodies in the Shanghai streets and the blood in the water around the ships being full of body parts of people killed by the strafing planes:

that same view in 1998 when Yoshiko visited Shanghai:

After the planes left, Yoshiko was calmly asked to continue her concert, which she did, although as you might expect, her singing "was well off the mark".

August 1945 - Japan defeated

On August 10th or so, as Yamaguchi was commuting to her daily voice lesson, she noticed "hordes of people filling the streets" shouting phrases like "Japan has surrendered" and "The war has ended" and "China for the Chinese". Her voice-teacher Madam Vera Mazel informed her that Japan had already surrendered, and (in a prescient piece of good advice) told Yoshiko to "just keep singing" through the coming turmoil and upheaval. [this person Vera also stood by Yoshiko later in NYC, 1951 when the FBI came knocking and seeking 'information' on Yamaguchi].

On August 15th, everyone listened to hear the "Imperial Rescript on Surrender" and the voice of the Emporer for the first time. The speech is remarkable for what it says, what it does not say, and for the style of how it is written:

Yamaguchi says he sounded "no different" than anyone else, but it was clear that Japan had lost the war and was now a defeated nation.

She returned to her flat, changed clothes and promptly hailed a rickshaw, which she rode around Shanghai for the next few hours, soaking up the historic day, and alternately weeping as she went. Once again, she was a witness to history: this time to the fall of the Japanese empire as it was celebrated in the streets of Shanghai (and no doubt in every city in China also). If she had "been Japanese" as her critics maintain, certainly she would have felt extremely vulnerable riding around in a rickshaw.

watch the excellent 1989 depiction of this rickshaw ride here:

Dorama Kouranseries Video 2

Positions had suddenly reversed between over-lord and underling: all the Japanese flags were torn down, trampled and replaced with Chinese flags; a huge party-atmosphere took hold of the city filled with fire-crackers, gongs, and drums.

Yoshiko recalls going back to her flat and collapsing on the sofa, thinking about all she had seen that day. That evening, all she heard were the sounds of people celebrating, popping champagne bottles, and laughing and playing music "as though it were Christmas in August".

KMT Nationalist military forces swept into the city and very quickly set up relocation camps for the Japanese (instead of engaging in a revengeful blood-bath as you might expect they would). This photo from the above video shows the actual buildings in Hongkou where Yamaguchi and others were isolated under house-arrest:

The below plaque celebrates the Japanese abdication in Manchuria:

x--x--x--x--x

Unfortunately for Li Xianglan, the hybrid superstar of Manchurian Japanese birth and Chinese sensibility, the defeat of Imperial Japanese forces in the Pacific theater brought the curtain down on a famous Shanghai era; ended her Chinese-mainland career as Li Xianglan, and subsequently almost led to her execution as a "hanjian" (traitor) for her 'betrayal of China's national interests'. Here is the newspaper article announcing her arrest:

Some time after the formal Japanese surrender of September 9, 1945, Yoshiko was detained in a type of house-arrest along with other Japanese nationals. They were all required to live in the Hongkou relocation camp, a series of modern 3-story town-homes, typically all connected in rows:

a japanese website already investigated where this area was located in Shanghai:

http://uetoayarikoran.cocolog-nifty.com/blog/2007/07/post_78a7.html

see the circle in center of map below (the area was not too far from Broadway Mansion where Yoshiko stayed at the time):

Yamaguchi's party of four included three men connected with the film industry, in particular a prominent film producer named Kawakita Nagamasu. He acted as a 'guardian' or 'protector' for Yoshiko during the series of meetings with Chinese court-investigators who were questioning her closely about all the details of her life. Her memoir is sprinkled with references to these 'trial questions', which have the habit of appearing in the form of curious answers which Yoshiko reveals to us, sometimes without telling us what the original questions were.

Apparently, some of her jailors loved her music and when she would sing, everyone from jailors to the detained would listen in appreciation. And this is a pattern: of people who were less concerned about her movie roles and totally enthralled by the songs and the beauty which created them. [Actually, they were created by a talented and diverse mix of Chinese, Japanese, Russian, American, and other musicians, and we can only marvel today at their beautiful creations, made during a time of unimaginable wartime brutality.]

Here are shots of the courtroom in Shanghai where her trial was held:

she would have climbed these stairs:

x--x--x--x--x

During these last few months of mid-summer 1945 prior to Japan's formal acceptance of defeat, everyone in Shanghai with access to short-wave radio or other 'outside information' was aware that the end was indeed near.

One day, Li Xianglan was requested to sing for a group of dignitaries at the Cathay Hotel (built by Victor Sassoon 1929 on the Huangpo River: The Cathay Hotel now called The Peace Hotel:)

As she started to sing, air-raid sirens went off, bombs started falling, and American planes were diving and strafing with machine-guns. Everyone ran down to the basement and huddled in the dark, wondering if they would all be killed by bombs that were shaking the building like earthquakes. This terrifying scene lasted about an hour:

She recalls with horror the sight from an upper floor: of "heaps" of dead bodies in the Shanghai streets and the blood in the water around the ships being full of body parts of people killed by the strafing planes:

that same view in 1998 when Yoshiko visited Shanghai:

After the planes left, Yoshiko was calmly asked to continue her concert, which she did, although as you might expect, her singing "was well off the mark".

By this time, most major cities in Japan had been bombed and burned by American incendiary bombs, eliciting a greater toll of lives than even the atomic weapons did.

The first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6th. Shanghai newspapers reported it was a "new-style bomb".

But 'the show must go on'. And so on August 9th, Li Xianglan and orchestra performed an encore of her "Evening Primrose Rhapsody" on the grounds of the Shanghai Racecourse:

The first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6th. Shanghai newspapers reported it was a "new-style bomb".

But 'the show must go on'. And so on August 9th, Li Xianglan and orchestra performed an encore of her "Evening Primrose Rhapsody" on the grounds of the Shanghai Racecourse:

According to her memories of this concert, everyone of every nationality "paraded in their finest summer fashions while strolling the race-grounds as though in a summer daydream". Subconsciously they probably knew that this was the end of an era.

x--x--x--x--x

On this same day that Li Xianglan sang her favorite songs, the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, and the Russian-Soviet army invaded Manchuria.

x--x--x--x--x

August 1945 - Japan defeated

On August 10th or so, as Yamaguchi was commuting to her daily voice lesson, she noticed "hordes of people filling the streets" shouting phrases like "Japan has surrendered" and "The war has ended" and "China for the Chinese". Her voice-teacher Madam Vera Mazel informed her that Japan had already surrendered, and (in a prescient piece of good advice) told Yoshiko to "just keep singing" through the coming turmoil and upheaval. [this person Vera also stood by Yoshiko later in NYC, 1951 when the FBI came knocking and seeking 'information' on Yamaguchi].

On August 15th, everyone listened to hear the "Imperial Rescript on Surrender" and the voice of the Emporer for the first time. The speech is remarkable for what it says, what it does not say, and for the style of how it is written:

Yamaguchi says he sounded "no different" than anyone else, but it was clear that Japan had lost the war and was now a defeated nation.

She returned to her flat, changed clothes and promptly hailed a rickshaw, which she rode around Shanghai for the next few hours, soaking up the historic day, and alternately weeping as she went. Once again, she was a witness to history: this time to the fall of the Japanese empire as it was celebrated in the streets of Shanghai (and no doubt in every city in China also). If she had "been Japanese" as her critics maintain, certainly she would have felt extremely vulnerable riding around in a rickshaw.

watch the excellent 1989 depiction of this rickshaw ride here:

Dorama Kouranseries Video 2

Positions had suddenly reversed between over-lord and underling: all the Japanese flags were torn down, trampled and replaced with Chinese flags; a huge party-atmosphere took hold of the city filled with fire-crackers, gongs, and drums.

Yoshiko recalls going back to her flat and collapsing on the sofa, thinking about all she had seen that day. That evening, all she heard were the sounds of people celebrating, popping champagne bottles, and laughing and playing music "as though it were Christmas in August".

KMT Nationalist military forces swept into the city and very quickly set up relocation camps for the Japanese (instead of engaging in a revengeful blood-bath as you might expect they would). This photo from the above video shows the actual buildings in Hongkou where Yamaguchi and others were isolated under house-arrest:

The below plaque celebrates the Japanese abdication in Manchuria:

x--x--x--x--x

Unfortunately for Li Xianglan, the hybrid superstar of Manchurian Japanese birth and Chinese sensibility, the defeat of Imperial Japanese forces in the Pacific theater brought the curtain down on a famous Shanghai era; ended her Chinese-mainland career as Li Xianglan, and subsequently almost led to her execution as a "hanjian" (traitor) for her 'betrayal of China's national interests'. Here is the newspaper article announcing her arrest:

Some time after the formal Japanese surrender of September 9, 1945, Yoshiko was detained in a type of house-arrest along with other Japanese nationals. They were all required to live in the Hongkou relocation camp, a series of modern 3-story town-homes, typically all connected in rows:

a japanese website already investigated where this area was located in Shanghai:

http://uetoayarikoran.cocolog-nifty.com/blog/2007/07/post_78a7.html

see the circle in center of map below (the area was not too far from Broadway Mansion where Yoshiko stayed at the time):

Yamaguchi's party of four included three men connected with the film industry, in particular a prominent film producer named Kawakita Nagamasu. He acted as a 'guardian' or 'protector' for Yoshiko during the series of meetings with Chinese court-investigators who were questioning her closely about all the details of her life. Her memoir is sprinkled with references to these 'trial questions', which have the habit of appearing in the form of curious answers which Yoshiko reveals to us, sometimes without telling us what the original questions were.

Apparently, some of her jailors loved her music and when she would sing, everyone from jailors to the detained would listen in appreciation. And this is a pattern: of people who were less concerned about her movie roles and totally enthralled by the songs and the beauty which created them. [Actually, they were created by a talented and diverse mix of Chinese, Japanese, Russian, American, and other musicians, and we can only marvel today at their beautiful creations, made during a time of unimaginable wartime brutality.]

Here are shots of the courtroom in Shanghai where her trial was held:

she would have climbed these stairs:

Here is the Court's case:

"During the war, Li Xianglan sold out her country while pursuing her flamboyant movie-star career. When her transgressions are investigated, she now proclaims that she is Japanese, confines herself within Japanese quarters, and attempts to flee to Japan. That's what most people think. . . the fact there have been rumors about your execution is a demonstration of their desire to drag you out of relocation camp, throw you in prison, and have you go through a thorough and impartial trial. They believe that the rightful outcome, should you have any Chinese blood, is that you be punished as a hanjian (traitor)." the court accused her of being "a Chinese imposter who used her outstanding beauty to make films that humiliated China and compromised Chinese dignity".

Yamaguchi's account of her detainment in the Hongkou relocation camp row houses, is filled with tears, laughter, suspense, and terror. At various times in these months, for example,

Upon receiving word that Yoshiko needs proof of her Japanese ancestry in order to avoid the death penalty, her parents sew an old stained copy of the birth registry into a hem of Yoshiko's childhood play-doll (called a fuji-musume). They box the doll as a gift and give it to Lyuba, who then flies back to Shanghai and has it delivered to Yoshiko.

This stained old piece of paper saved Li Xianglan's life! but it was not the only thing that did it - by many Chinese accounts the courtroom was full of spectators who were shouting for Li's head and the verdict was being swayed to 'guilty as charged', but Li stood up and tearfully sang her heart out for her life, singing her most popular Chinese songs, which gradually won over the crowd who had just called for her head on a platter!

In mid-February, Yoshiko was cleared of the charge of treason. The court expressed it's regret over the fact that Yoshiko had appeared in such films as "China Nights" under her stage name of Li Xianglan. In accordance with the eastern approach to justice, Yamaguchi offered her profound apology, which the court found acceptable. In the milieu of the times in China, this mercy was called "returning bad actions with good".

[Ed: in my opinion, the fact that Yamaguchi was born to Japanese parents and in a Japanese registry was only a 'face-saving' excuse which gave the court legal cover to absolve her of treason against her own country. Finding out she was Japanese, they could have declared her one of the enemy and judged her for 'cultural crimes' accordingly.]

One has to believe that no one entity (ie, Nationalist or Communist) wanted to be responsible for the execution of a star of the magnitude of Li Xianglan, because she had so many fans on all sides of the conflict. And in hindsight, it reflects very well on the (Chinese) court that they were merciful and allowed her to repatriate to Japan. Placing her under house-arrest with a Chinese soldier guarding the door also prevented any mob of incensed vigilantes from taking the law into their own hands (average Chinese sentiment was that she was Chinese and a traitor).

Yoshiko and her fellow-detainees from the movie industry tried to leave Shanghai immediately as the court had ordered in February, but at the last minute while boarding the ship, an irate Chinese police-officer recognized her, calling out "That's Li Xianglan!", causing quite a commotion and officiously ordering her back to the relocation camp. Yoshiko thought she might never be allowed to leave China and if one branch of the government was opposing the other branch, it would spell her doom. Finally, through the auspices of a kindly old judge who personally accompanied her to the harbor, Yoshiko boarded another ship bound for Japan.

This is Yoshiko's Repatriation Permit, complete with medical inspection stamp, dated March 27th, 1946:

leaving China behind in late March 1946 and her name, life, and work as Li Xianglan:

this is the "Sayonara Ri Koran" scene while her "Evening Primrose" song is wafting out of the PA speakers as the boat leaves Shanghai harbor at dusk:

It would be more than twenty years before she would see China again.

It must have been truly devastating to the just turned 26yr old to be on that ship. She had worked so hard all of her young life to build a career; she had attained that goal spectacularly and future greatness was within her grasp, and then, within a few months time the whole structure of her life was completely destroyed.

But remember, this was a person who had personally seen death up close at the age of 12; who had bandaged broken bodies and sung to dying soldiers the sounds they would hear with their last breaths of life, and who witnessed the bombing of Shanghai, so she had already gone through extreme 'life and death' situations.

She had come from a society that revered stoicism and discipline in the face of adversity, and she applied that same single-minded unbending will to the next tasks at hand. She had to regroup, recover, and above all, continue working (as the whole nation had to do the same). Just a few days later, while still on the ship she is asked to sing her "Evening Primrose" show-songs on the main-deck.

"Thinking about it now, if citizenship had been granted by place of birth (as is the case in America today) as someone born in Manchuria I could have held Manchurian citizenship. I think I likely would have gone about things a bit differently. But the rigidity of the situation was such that Japan was my homeland, and I was a Japanese. In addition, Japan and China (two countries that should be the closest of friends) were at war. In the midst of all this, I too-simply believed in the slogan of "Goodwill between Japan and Manchuria". The below photo appeared in Yoshiko's last book:

Arriving back to Japan on April 1, 1946. Nagamasa Kawakita (her protector during her detainment) is on the left side of this picture:

Unbeknownst to Yoshiko at the time, the Americans opened a file on her as a person of interest because of her alleged 'association with known communists' while in China.

The intelligence file would cause her much future grief when she would be denied a visa to return to the United States.

Concerning her next series of career moves, Yamaguchi writes candidly that she tried hard to restart as a vocalist, and then as a stage actress, but failed at both endeavors. Well, perhaps failure for her would have been judged an acceptable success for a mere mortal . . . in any case, she then decided to get back into the film world.

Meanwhile, in a forgotten chapter of history, approximately 1.7 million Japanese who had migrated to Manchuria over some forty years of time and who had tried to build a new life there, were now faced with expulsion. The Yamaguchi family was just one such family.

This operation was called repatriation from Port Huludao: you can read the story in this link:

http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2011/8/16/escape-from-manchuria/

"During the war, Li Xianglan sold out her country while pursuing her flamboyant movie-star career. When her transgressions are investigated, she now proclaims that she is Japanese, confines herself within Japanese quarters, and attempts to flee to Japan. That's what most people think. . . the fact there have been rumors about your execution is a demonstration of their desire to drag you out of relocation camp, throw you in prison, and have you go through a thorough and impartial trial. They believe that the rightful outcome, should you have any Chinese blood, is that you be punished as a hanjian (traitor)." the court accused her of being "a Chinese imposter who used her outstanding beauty to make films that humiliated China and compromised Chinese dignity".

Yamaguchi's account of her detainment in the Hongkou relocation camp row houses, is filled with tears, laughter, suspense, and terror. At various times in these months, for example,

- she is offered a fine house with servants, a Cadillac with a chauffeur, if only she will accept the role of spying on communist activity in the northeast (Manchuria)

- or come up with $5,000 to buy her way to freedom (well... if you can't afford $5,000 we'll drop the price to $3,000... how about it?)

- newspapers and wall-graffiti list Kawashima, Tokyo Rose and Yamaguchi as the 3 main 'hanjian' who will be executed soon - here's the news clipping with Kawashima's name on top of the list, followed by Rose and Li Xianglan at bottom:

- a Senior Chinese General wants to make Li Xianglan his eighth concubine - he shows up with a convoy of vehicles and demands she be handed over - she hides in the bathroom again and avoids this fate

- the Japanese have a clandestine short-wave radio which they use at night to listen to BBC, etc - in the daytime the radio parts are hidden all over the house

- Yamaguchi bemoans the fact "my face had something in common with people all over the world, except Japan"

- a newspaper prints a scoop: Li Xianglan will be executed on Dec 8th 1945 at the Shanghai Racecourse! one can imagine the terror with each knock on the door as this day came and went

Upon receiving word that Yoshiko needs proof of her Japanese ancestry in order to avoid the death penalty, her parents sew an old stained copy of the birth registry into a hem of Yoshiko's childhood play-doll (called a fuji-musume). They box the doll as a gift and give it to Lyuba, who then flies back to Shanghai and has it delivered to Yoshiko.

This stained old piece of paper saved Li Xianglan's life! but it was not the only thing that did it - by many Chinese accounts the courtroom was full of spectators who were shouting for Li's head and the verdict was being swayed to 'guilty as charged', but Li stood up and tearfully sang her heart out for her life, singing her most popular Chinese songs, which gradually won over the crowd who had just called for her head on a platter!

In mid-February, Yoshiko was cleared of the charge of treason. The court expressed it's regret over the fact that Yoshiko had appeared in such films as "China Nights" under her stage name of Li Xianglan. In accordance with the eastern approach to justice, Yamaguchi offered her profound apology, which the court found acceptable. In the milieu of the times in China, this mercy was called "returning bad actions with good".

[Ed: in my opinion, the fact that Yamaguchi was born to Japanese parents and in a Japanese registry was only a 'face-saving' excuse which gave the court legal cover to absolve her of treason against her own country. Finding out she was Japanese, they could have declared her one of the enemy and judged her for 'cultural crimes' accordingly.]

One has to believe that no one entity (ie, Nationalist or Communist) wanted to be responsible for the execution of a star of the magnitude of Li Xianglan, because she had so many fans on all sides of the conflict. And in hindsight, it reflects very well on the (Chinese) court that they were merciful and allowed her to repatriate to Japan. Placing her under house-arrest with a Chinese soldier guarding the door also prevented any mob of incensed vigilantes from taking the law into their own hands (average Chinese sentiment was that she was Chinese and a traitor).

Yoshiko and her fellow-detainees from the movie industry tried to leave Shanghai immediately as the court had ordered in February, but at the last minute while boarding the ship, an irate Chinese police-officer recognized her, calling out "That's Li Xianglan!", causing quite a commotion and officiously ordering her back to the relocation camp. Yoshiko thought she might never be allowed to leave China and if one branch of the government was opposing the other branch, it would spell her doom. Finally, through the auspices of a kindly old judge who personally accompanied her to the harbor, Yoshiko boarded another ship bound for Japan.

This is Yoshiko's Repatriation Permit, complete with medical inspection stamp, dated March 27th, 1946:

leaving China behind in late March 1946 and her name, life, and work as Li Xianglan:

this is the "Sayonara Ri Koran" scene while her "Evening Primrose" song is wafting out of the PA speakers as the boat leaves Shanghai harbor at dusk:

It must have been truly devastating to the just turned 26yr old to be on that ship. She had worked so hard all of her young life to build a career; she had attained that goal spectacularly and future greatness was within her grasp, and then, within a few months time the whole structure of her life was completely destroyed.

But remember, this was a person who had personally seen death up close at the age of 12; who had bandaged broken bodies and sung to dying soldiers the sounds they would hear with their last breaths of life, and who witnessed the bombing of Shanghai, so she had already gone through extreme 'life and death' situations.

She had come from a society that revered stoicism and discipline in the face of adversity, and she applied that same single-minded unbending will to the next tasks at hand. She had to regroup, recover, and above all, continue working (as the whole nation had to do the same). Just a few days later, while still on the ship she is asked to sing her "Evening Primrose" show-songs on the main-deck.

In her 2004 interview with Tanaka, Utsumi, and Onuma, Yoshiko says this:

"Thinking about it now, if citizenship had been granted by place of birth (as is the case in America today) as someone born in Manchuria I could have held Manchurian citizenship. I think I likely would have gone about things a bit differently. But the rigidity of the situation was such that Japan was my homeland, and I was a Japanese. In addition, Japan and China (two countries that should be the closest of friends) were at war. In the midst of all this, I too-simply believed in the slogan of "Goodwill between Japan and Manchuria". The below photo appeared in Yoshiko's last book:

x--x--x--x--x

Arriving back to Japan on April 1, 1946. Nagamasa Kawakita (her protector during her detainment) is on the left side of this picture:

Unbeknownst to Yoshiko at the time, the Americans opened a file on her as a person of interest because of her alleged 'association with known communists' while in China.

The intelligence file would cause her much future grief when she would be denied a visa to return to the United States.

Concerning her next series of career moves, Yamaguchi writes candidly that she tried hard to restart as a vocalist, and then as a stage actress, but failed at both endeavors. Well, perhaps failure for her would have been judged an acceptable success for a mere mortal . . . in any case, she then decided to get back into the film world.

x--x--x--x--x

Meanwhile, in a forgotten chapter of history, approximately 1.7 million Japanese who had migrated to Manchuria over some forty years of time and who had tried to build a new life there, were now faced with expulsion. The Yamaguchi family was just one such family.

This operation was called repatriation from Port Huludao: you can read the story in this link:

http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2011/8/16/escape-from-manchuria/

No comments:

Post a Comment