An interesting Dissertation by Yue Chen: Women's Mobility in Manchukuo Films. First and foremost in this paper, you will learn positive things that no one else has expressed about Ri Koran's films (and as a bonus you won't see the words "puppet state").

and here's her June 2018 PhD thesis link. This thesis has an interesting Chapter 5 on Ri Koran and her "legendary" film-musical "My Nightingale".

Yue Chen has a more nuanced view of Manchukuo than the 'usual suspects', which is refreshing.

x--x--x--x--x

Mia Fan Ni wrote the following for her Master's thesis in 2019: Ri Koran/Li Xianglan : Visual Reality and Historical Truth. here is her thesis summary:

Li Xianglan, or Ri Koran in Japanese, was a screen sensation and popular culture icon during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Her story of success, however, was overshadowed by her hidden identity as Yamaguchi Yoshiko, a Manchurian-born Japanese promoting Japanese imperialist ideology through the guise of her on-screen Chinese personae. The National Policy Company Manchurian Film Association (Man'ei for short) was established by the Kwantung Army to accelerate the dissemination of Japanese imperialist propaganda. The choice of Ri Koran as the face of Man'ei underlines the significance of her controversial and ambiguous allure, which enabled her to navigate, or “border cross,” the complex waters of wartime politics and popular culture during the Sino-Japanese conflict. Through a detailed analysis of one of the Continental Trilogy of films, China Nights (1940), this thesis illustrates how Ri Koran was crafted into a living embodiment of “Hakko Ichiu”, the guiding ideological principle of The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. I investigate the manifestation of “Hakko Ichiu” (Gozoku Kyowa in the Manchurian context) though analysis of particular scenes in the film as well as its use of music, historically known as Continental Melodies. Drawing from existing scholarship by both historians and film scholars, this thesis establishes an important link between these two previously separate scholarly discourses on Ri Koran.

x--x--x--x--x

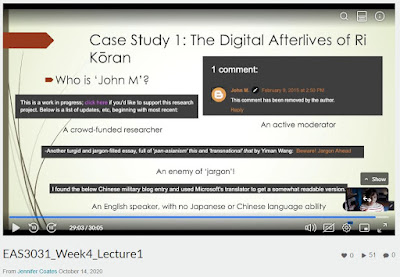

Jennifer Coates wrote "The Shape-Shifting Diva: Yamaguchi Yoshiko and the National Body" (behind a paywall):

"This article addresses the postwar film career (1948–1958) of Japanese actress Yamaguchi Yoshiko to suggest that understanding the star persona as ‘diva’ can uncover the affective value of star images for contemporary audiences. The diva persona is often typified by symbols and iconography that transform the actress into something non-human or transcendental. Many scholars and critics of Japanese film have struggled to put this transformative aspect of the female star persona into words, presenting the affective impact of the diva as inexplicable. Attempting to shed light on the affect of the diva persona in Japanese cinema, this article suggests that diva images are invested with particular affects that reflect and mediate national issues. Reading Yamaguchi's star persona in the context of the drastic socio-political change of the early postwar era reveals the expressive and mediative qualities of the diva image at work in the aftermath of Japanese defeat and occupation (1945–1952), and suggests that Yamaguchi's enduring popularity and political influence are based in the national implications of her diva performances.

Professor Coates is a prolific worker-bee in the "everything is gender" hive:

she has many hard to find videos posted on this page:

several of these videos concern our hero and reference the blog you now read:

x--x--x--x--x

if you can get past stuff like the above, Chikako Nagayama has written a 175pg thesis which contains good summaries of the "continental trilogy" films (Song of the White Orchid, China Nights, Vow in the Desert, and Suzhou Nights) as well as a good amount of historical information about Japanese culture in general:Although Chikako uses a large number of jargon words, when/if you can get past them you can appreciate her honestly expressed thoughts about Ri Koran:

x--x--x--x--x

PhD Thesis of reader Alison Luke dated May 2016:

COMMENTARY | THE VIEW FROM NEW YORK

The life and times of a Manchurian girl

BY HIROAKI SATO

NEW YORK — The New York Times’ recent reprinting of a cartoon showing Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat gagged and bound to a chair while Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon presses him to “say something! do something!” made me think of Rikoran, known today mainly as Yoshiko Yamaguchi.

A little before the cartoon appeared, my friend Inuhiko Yomota had written: “Yamaguchi tells me she can’t die until the Palestinians are liberated. She’s still so hale you can’t believe she’s 82!”

Moved by Beijing film director Chen Kaige’s (“The Emperor and the Assassin”) assertion that “Li Xianglan ( Chinese pronunciation of Rikoran) is the most important woman that 20th-century Asia has produced,” Yomota, semanticist and film historian, has dealt with the actress-singer turned politician in two books: Yomota wrote “Nihon no Joyu” (“Japanese Actresses,” Iwanami, 2000), in which he analyzes her career along with that of Setsuko Hara. And he edited “Rikoran to Higashi Ajia” (“Rikoran and East Asia,” Tokyo Daigaku, 2001).

Yamaguchi was born in 1920, near Mukden (now Shenyang), to an adviser to the Southern Manchurian Railroad. When Japan invaded northern China, she remembers her father saying, “There’s no way of winning a war against this unfathomable land of China.”

When she was 12, Japan established Manchukuo, and she witnessed executions of Chinese guerrillas. At 13, she was adopted by Gen. Li Jichun, a former leader of “horse bandits” and now chairman of the Bank of Shenyang, and was given the Chinese name Li Xianglan. At the suggestion of her close friend, a Jewish-Russian girl, she studied voice with an Italian opera singer who had gained fame in imperial Russia. She was a natural and soon debuted on the radio, recognized as a Chinese performer.

In 1934, the Yamaguchi family moved to Beijing, where she attended a Chinese missionary school for girls. As anti-Japanese sentiments mounted, her friends, not knowing she was Japanese, put her in a quandary by asking what she intended to do to fight the Japanese.

In 1938 she debuted in a movie made by the newly created Manchurian Film Studio, which, after Mao Zedong’s takeover, would teach film-making techniques to the Communist Party. She would make movies in Japan, Korea, Taiwan and, after the war, in Hollywood. Most of them dealt with contemporary issues of war and its consequences. Her increasing popularity even captured the imagination of American soldiers during the war.

My eminent friend Herbert Passin recalled in “Encounter With Japan” (Kodansha, 1983): “The all-time hit in Company A was ‘China Night’ (‘Shina no Yoru’), with Kazuo Hasegawa as the male lead and the popular actress Yoshiko Yamaguchi as the female lead. … When Hasegawa’s patient wooing of the bitter ‘Manchurian’ Rikoran finally succeeded and the two entered what to us was an ‘international’ (relationship) and in the movie was a ‘Greater East Asian’ relationship, we cheered as if he were one of us, instead of one of the enemy.”

“Shina no Yoru” (1940) was set in Shanghai after “peace” was restored following Japan’s assault on the city in 1937. The Chinese regarded Li Xianglan’s allowing a Japanese to slap her before she yielded to him on film as an insult to China. For that role she was tried as a traitor after Japan’s defeat. She was acquitted only when her Jewish-Russian friend rushed to the court with papers to prove she was Japanese.

She starred in two Hollywood movies, “Japanese War Bride” by King Vidor (1952) and “House of Bamboo” by Samuel Fuller (1955) under the name Shirley Yamaguchi. Japanese critics fumed that Fuller’s movie, in its disregard of Japanese habits, was a “national insult.” Yamaguchi, having played Chinese roles under Japanese directors, had to wonder, did Japanese critics fume at Japanese movies that disregarded Chinese manners?

Her 1951 marriage to Isamu Noguchi fell apart partly because of the sculptor’s rigid approach to Japanese culture. In 1958 she married a Japanese diplomat and retired from movie acting.

In 1969 she became a regular on, “You at Three O’clock,” a TV talk show for housewives. Participating celebrities were merely expected to gossip about the entertainment world. Yamaguchi, however, turned herself into a political journalist with a focus on refugee issues.

In 1970 she covered Cambodia. The 7,000 refugees she faced on the Laotian border reminded her of war dislocations she had experienced three decades earlier. In 1971 she made the first of three visits to the Middle East to take up the Palestinian question. One of her last reports on the region won a prize.

In 1974 she wrote her first book; it was about the Arabs. The same year she was elected to the House of Councilors, where she served until 1993, the last two years as chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations. When Micehl Khleifi’s “Wedding in Galilee,” the first movie drama made in Palestine, came out in 1987, she had it screened in Parliament.

As Yomota sees it, Yamaguchi’s stance on the Palestinian question is based on (1) her view that the Palestinians are being forced to compensate for the European persecution of Jews and (2) thoughts she conveyed to Yomota in an interview, reflecting her early life as a Japanese who rose to film stardom as a “Manchurian girl” in the midst of a war.

Although recognizing that Manchuria and the Middle East don’t bear ready comparison, she observed that, like Manchukuo, Israel may be “a state that came into being when it shouldn’t have.”

Politically, these views are likely to be at once naive and incendiary. But therein seems to lie one basic aspect of the intractability of the problem.

x--x--x--x--x

- the 1996 book titled World War II, Film, and History by John Chambers has a chapter by Freda Freiberg titled China Nights (Japan 1940) p. 31 - 46. She has some interesting comments to make because she thinks the "inter-racial" aspect of the film (as she terms the romance between a Chinese and Japanese) has been overlooked. Despite this misconception about the oriental race, her essay is worth reading as a proto-typical example of early-sceptical western academic work on Yamaguchi.

x--x--x--x--x

Stephenson: A Star by Any Other Name:

x--x--x--x--x

Stephenson: Her Traces Are Found Everywhere:

x--x--x--x--x

-this article appeared in Japan Times in 2002, and has lots of interesting information:COMMENTARY | THE VIEW FROM NEW YORK

The life and times of a Manchurian girl

BY HIROAKI SATO

NEW YORK — The New York Times’ recent reprinting of a cartoon showing Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat gagged and bound to a chair while Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon presses him to “say something! do something!” made me think of Rikoran, known today mainly as Yoshiko Yamaguchi.

A little before the cartoon appeared, my friend Inuhiko Yomota had written: “Yamaguchi tells me she can’t die until the Palestinians are liberated. She’s still so hale you can’t believe she’s 82!”

Moved by Beijing film director Chen Kaige’s (“The Emperor and the Assassin”) assertion that “Li Xianglan ( Chinese pronunciation of Rikoran) is the most important woman that 20th-century Asia has produced,” Yomota, semanticist and film historian, has dealt with the actress-singer turned politician in two books: Yomota wrote “Nihon no Joyu” (“Japanese Actresses,” Iwanami, 2000), in which he analyzes her career along with that of Setsuko Hara. And he edited “Rikoran to Higashi Ajia” (“Rikoran and East Asia,” Tokyo Daigaku, 2001).

Yamaguchi was born in 1920, near Mukden (now Shenyang), to an adviser to the Southern Manchurian Railroad. When Japan invaded northern China, she remembers her father saying, “There’s no way of winning a war against this unfathomable land of China.”

When she was 12, Japan established Manchukuo, and she witnessed executions of Chinese guerrillas. At 13, she was adopted by Gen. Li Jichun, a former leader of “horse bandits” and now chairman of the Bank of Shenyang, and was given the Chinese name Li Xianglan. At the suggestion of her close friend, a Jewish-Russian girl, she studied voice with an Italian opera singer who had gained fame in imperial Russia. She was a natural and soon debuted on the radio, recognized as a Chinese performer.

In 1934, the Yamaguchi family moved to Beijing, where she attended a Chinese missionary school for girls. As anti-Japanese sentiments mounted, her friends, not knowing she was Japanese, put her in a quandary by asking what she intended to do to fight the Japanese.

In 1938 she debuted in a movie made by the newly created Manchurian Film Studio, which, after Mao Zedong’s takeover, would teach film-making techniques to the Communist Party. She would make movies in Japan, Korea, Taiwan and, after the war, in Hollywood. Most of them dealt with contemporary issues of war and its consequences. Her increasing popularity even captured the imagination of American soldiers during the war.

My eminent friend Herbert Passin recalled in “Encounter With Japan” (Kodansha, 1983): “The all-time hit in Company A was ‘China Night’ (‘Shina no Yoru’), with Kazuo Hasegawa as the male lead and the popular actress Yoshiko Yamaguchi as the female lead. … When Hasegawa’s patient wooing of the bitter ‘Manchurian’ Rikoran finally succeeded and the two entered what to us was an ‘international’ (relationship) and in the movie was a ‘Greater East Asian’ relationship, we cheered as if he were one of us, instead of one of the enemy.”

“Shina no Yoru” (1940) was set in Shanghai after “peace” was restored following Japan’s assault on the city in 1937. The Chinese regarded Li Xianglan’s allowing a Japanese to slap her before she yielded to him on film as an insult to China. For that role she was tried as a traitor after Japan’s defeat. She was acquitted only when her Jewish-Russian friend rushed to the court with papers to prove she was Japanese.

She starred in two Hollywood movies, “Japanese War Bride” by King Vidor (1952) and “House of Bamboo” by Samuel Fuller (1955) under the name Shirley Yamaguchi. Japanese critics fumed that Fuller’s movie, in its disregard of Japanese habits, was a “national insult.” Yamaguchi, having played Chinese roles under Japanese directors, had to wonder, did Japanese critics fume at Japanese movies that disregarded Chinese manners?

Her 1951 marriage to Isamu Noguchi fell apart partly because of the sculptor’s rigid approach to Japanese culture. In 1958 she married a Japanese diplomat and retired from movie acting.

In 1969 she became a regular on, “You at Three O’clock,” a TV talk show for housewives. Participating celebrities were merely expected to gossip about the entertainment world. Yamaguchi, however, turned herself into a political journalist with a focus on refugee issues.

In 1970 she covered Cambodia. The 7,000 refugees she faced on the Laotian border reminded her of war dislocations she had experienced three decades earlier. In 1971 she made the first of three visits to the Middle East to take up the Palestinian question. One of her last reports on the region won a prize.

In 1974 she wrote her first book; it was about the Arabs. The same year she was elected to the House of Councilors, where she served until 1993, the last two years as chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations. When Micehl Khleifi’s “Wedding in Galilee,” the first movie drama made in Palestine, came out in 1987, she had it screened in Parliament.

As Yomota sees it, Yamaguchi’s stance on the Palestinian question is based on (1) her view that the Palestinians are being forced to compensate for the European persecution of Jews and (2) thoughts she conveyed to Yomota in an interview, reflecting her early life as a Japanese who rose to film stardom as a “Manchurian girl” in the midst of a war.

Although recognizing that Manchuria and the Middle East don’t bear ready comparison, she observed that, like Manchukuo, Israel may be “a state that came into being when it shouldn’t have.”

Politically, these views are likely to be at once naive and incendiary. But therein seems to lie one basic aspect of the intractability of the problem.

x--x--x--x--x

Manchukuo is becoming more popular as people who lived there as children grow older and write down their impressions. Here is an autobiographical novel written by an author born in 1937:

Recently I also found Manchurian Legacy, an autobiography by Kazuko Kuramoto, who was born in 1927 and lived with her family in Dairen:

No comments:

Post a Comment