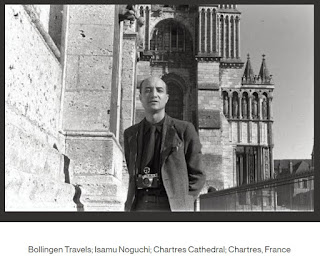

Between 1949 and 1956, sculptor Isamu Noguchi received grants from Paul and Mary Conover Mellon’s Bollingen Foundation, which had been actively supporting the translation into English of the writings of Carl Jung and early pan-Asian texts. Noguchi was born in the US in 1904 to an Irish-American mother and an absent Japanese father, grew up in Japan between the ages of three and thirteen, and self-incarcerated in 1942 at the Japanese internment camp in Poston, Arizona. He was the perfect recipient and interlocutor for the Bollingen Foundation’s mission of deepening the understanding between Eastern and Western cultures after World War II.

With the foundation’s support, Noguchi was able to travel around the world for seven years to conduct research for a book called Environments of Leisure, which he never completed. He said of his intention for the grant, “It is proposed to make a comprehensive study of the physical aspect of the environment of leisure, its meaning, its use, and its relationship to society. The study will be directed to community enjoyed leisure space. Special attention will be given to the contemplative uses of leisure (for the recreation of the mind) and to the play world of childhood ... it is hoped that the results may be published in order to invite planning of more beautiful and rewarding communities.”

His journeys allowed him to see sites in France, Italy, Spain, Greece, England, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Nepal, Egypt, India, Sri Lanka, Bali, Thailand, Cambodia and Japan. Along the way, Noguchi drew and photographed prehistoric cave drawings, stupas, Jantar Mantar and other astrono- mical observatories, menhirs (prehistoric standing stones), burial mounds, temples, playgrounds, churches, public squares, Balinese shadow-puppet plays, Japanese gardens, and Buddhist monuments. Experiencing personally these ancient cultural sites, in which objects, architecture, and landscape fulfilled “their communal, emotional and mystical purposes,” had a profound impact on Noguchi. His ideas about what modern sculpture could do encompassed not only the formal and aesthetic, but also an understanding of how sculpture could affect the human psyche and the environment, and in turn activate the social and ritualistic functions of engagement with and enjoyment of public space.

As a result of these travels, Noguchi began to focus on abstract and universal sculptural ideas that explored everything from archaic geological time to cosmology, mythology, humanism, garden design, and the importance of site and scale. His works and proposals (finished and unfinished) during this time – like the bust of Jawaharlal Nehru, the Hiroshima memorial and Peace Bridge, a monument to Gandhi, the UNESCO garden commissioned by Marcel Breuer, and even the prototyping and production of his Akari lanterns in Gifu, Japan – all synthesized Noguchi’s desire to redirect traditional ways of doing things towards the future and his efforts to understand how to “braid” time in new ways.

No comments:

Post a Comment